-Stude I LAW STUDENT DIVISION AM

advertisement

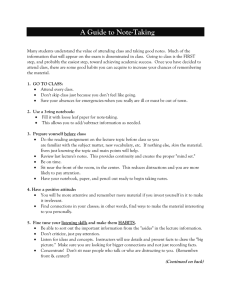

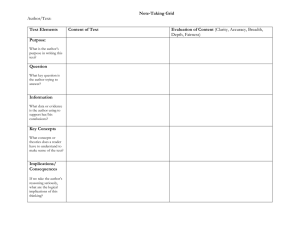

-Stude LAW STUDENT DIVISION I AM SEPTEMBER 2010 I VOLUME Adviser Making smart decisions for the classroom BY AMY L. JARMON CLASSES REQUIRE different strategies than undergraduate classes because of format, content, and pace differences. Law professors rarely lecture because they expect students to understand basic concepts during class preparation. They may use the Socratic Method of questioning to reveal legal analysis and nuances. Professors also tend to cover more material quickly. As a result of this analysis, a student will immediately have a better idea of the class format that will be followed, the expectations for student preparation, the likely questions to be' asked, supplemental formats used by the professor, and the keywords signifying important points. Most professors folIowa pattern in their class format and their expectations for student participation. Each professor will have a personal style of teaching reflected in these patterns. Savvy class observation and analysis can help students use these patterns to their advantage. ' #,w////,w//////,w/////.1W///#.1W//#/#////,w//////,w////##////#/ HERE ARE SOME OF THE QUESTIONS FOR ANALYZING EACH CLASS fOR THE RELEVANT PATTERNS 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 I STUDENT LAWYER I September 201 0 Does the professor begin class with a review of major points from the last class? Does the professor discuss in minute detail or in overview? 'Does the professor expect student recitation of precise issue and rule statements? Does the professor expect indepth discussion of the court's rationale? Is policy discussion important to the class? Does the professor foc.us on comments or notes at the end of a case? Does the professor present students with new hypothetical fact scenarios? 4' o o o o o What questions does the professor ask in nearly every class? What key phrases does the professor use to introduce important points? Does the professor post PowerPoint slides before or after class? Does the professor use the whiteboard for illustration purposes? Does the professor end with a summary of the important class points? Experiment for each class on what works best for you. Your decisions may vary because of professor or course content. &//////#////#/////#&/////'W//////#///////'(/&//////&////#&///###//&/#///#/#97///&/#////#&///#/&/// CONSIDER THE FOLLOWING ASPECTS OF NOTE-TAKING o o o Once you have figured out the pattern for a course, you can read and brief specifically for the needs of the class. You can also prepare for questions ahead of time. o #///#&/////#/#//////#////#/#////4W//////4W/4W/#/////#//////#/#/&/#////4W/#//##//#97/###///// o THINK ABOUT THE PROfESSOR'S fORMAT AND EXPECTATIONS BY USING THESE TIPS o o o o o o Focus your reading to address the aspects that the professor typically emphasizes and the questions typically asked in class. Prepare for the amount of detail that your professor wants in student responses. Think about and brief the cases on several levels: U What are the specifics for understanding this case itself? Cl What are the similarities and differences among cases if several will be discussed? o How can the legal rules and analysis of a specific case be used to solve future legal scenarios? Think carefully about the editor's questions, notes, and comments after the case and make margin notes of the most important points. Think about policy implications if your professor typically addresses policy. Change the facts of the case so that you can explore the implications from different angles. Take a few minutes to explain the case out loud to an empty chair-you must understand it to explain it properly. Outline the relevant topics and sub-topics on an index card to clarify the structure of the material in case you get lost during a fast-paced class. 10 I STUDENT LAWYER I September 201 0 o Make a conscious decision about handwriting or typing class notes. Verbal learners may learn better by handwriting their notes while kinesthetic-tactile learners may learn better by typing. Consider formatting your brief and notes for a case on the same page. Use the left third of the page for your brief. Use the remaining two-thirds of the page as your note-taking area. This method will help you avoid duplicating what is already correct in your brief and will facilitate later analysis of any errors that were in your brief. Evaluate your professor's PowerPoint slides. Will they be available before or after class? Will they form the base for your notes or supplement your notes? Do they cover all the key points or serve merely as a springboard to classroom discussion? Include the essentials in your notes: rules; exceptions to rules; jurisdictional variations of rules; tests; steps of analysis; cautions about common student errors; hypothetical examples; and summaries of key points. Determine whether any of the computer software options for organizing your briefs and class notes are helpful to you. Many students use OneNote and other software products. Adopt consistent abbreviations and symbols for legal terms as well as common words. A shorthand system saves lots of time in note-taking. STAY ENGAGED IN THEClASS RATHER THAN ZONE OUT o o o o Active listeners have increased focus, understanding, and recall. &////##/#///#/////&///#/&////////#///#&///&/&////#&//////#/#// YOU CAN GAIN MORE FROM CLASS TIME USING THE FOLLOWING TECHNIOUES Think while you listen rather than passively transcribing every word. Actively decide what to include or exclude in note-taking. Listen for clues to important information: "As I mentioned earlier.... " "Remember that the three steps are .... " "The policy implication is .... " Use your computer only for notes and class-related items. Avoid computer distractions such as Facebook, online shopping, IM-ing, or e-mailing. Answer the professor's questions silently in your head whenever another student recites. Compare your answers to that student's responses and consider the professor's feedback. wW\(\I.abanet.orglisd I American Bar Association oo ~z :ct-- r o o Volunteer to answer questions if appropriate. You will often learn more if you are involved in the discussion. Mark any places in your notes where you were 90nfused or missed part of the discussion. Return to those sections later to clarify or expand your notes. DO NOT CHECK YOUR COMMON SENSEATTHE CLASSROOM DOOR a a o a a for later outlining, and highlight questions you need to get answered. Consider asking permission to tape a class you find difficult. Instead of listening to an entire lecture again, fast-forward to parts where you became confused or missed what the professor said. //#/#///##////##///////#////z/#//////z//z//////z////##hW//# WEIGH THE FOLLOWING ASPECTS TO MAKE SOUND CLASSROOM AND NOTE-TAKING DECISIONS a Prepare for class carefully even if you will not have to recite. The best grades go to students with deep understanding of the material. If you skimp on prepara~ tion, your understanding will be minimal. Do not forfeit possible class participation points. Professors often "bump up" student grades or assign a percentage of the grade for participation. Avoid class "scripts" by prior students in the course. You will be less actively engaged in the class if you do not take your own notes. Pay attention to anything the professor writes on the whiteboard. If it was important enough to write on the whiteboard, you should include it in your notes. Review your class notes within 24 hours. Fill in gaps, reorganize jumbled notes, summarize the major points American Bar Association I www.abanet.orgllsd Think while you listen rather than passively trans(ribin~ 0 every word. Law school classes require consistent dedication. You need to prepare well and also stay focused during class. In addition, you need to review regularly after the class is over. ~1. Amy L. Jarmon (amy.jarmon@ttu.edu), assistant dean for academic success programs at Texas Tech University School of Law, is a professor and coeditor ofthe Law School Academic Support Blog. She has practiced law in the United States and the United Kingdom. September 201 0 I STUDENT LAWYER I 11