UCL Chamber Music Club Newsletter, No.5, October 2015 In this issue:

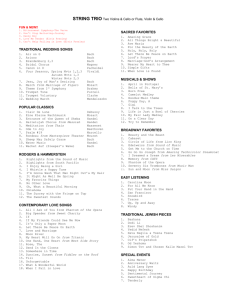

advertisement