Construction Workers’ Perception of Temporary Foreign Workers in Metro Vancouver

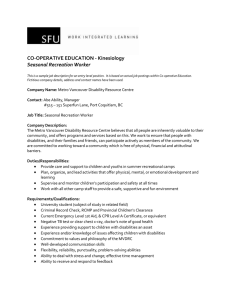

advertisement