P Q UK C

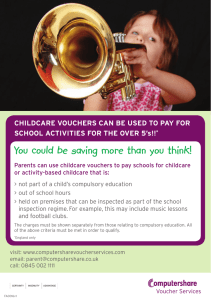

advertisement