Students’ Perceptions of the Value and Need for Mentors

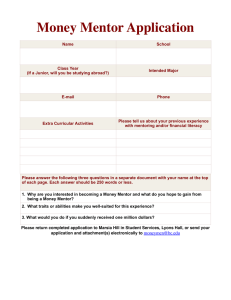

advertisement