My Recollections Lloyal O. Bacon

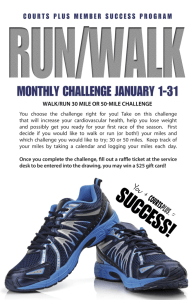

advertisement