Pulling Away: Managing and Sustaining Change

advertisement

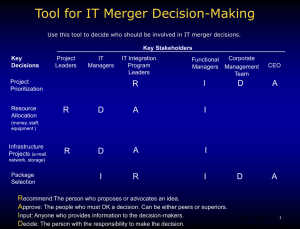

Pulling Away: Managing and Sustaining Change By Miles Cook The Vendée Globe sailing race, which started in November 2008 and just wrapped up in March, is one of the most brutal in the world. Competitors sail around the globe, single-handedly, without assistance and without touching land, starting and ending on the coast of France. The fastest path is straight south to Antarctica, around that continent and back north to the finish. Each competitor spends months in the southern ocean dodging mountainous waves, icebergs, tornadoes and gale-force storms. The fastest sailors in the calmer northern waters are often not the same ones in the lead after the turbulence of the Antarctic seas. In fact, 64 percent of the competitors who started the most recent race never even finished. That’s not a bad metaphor for the current economic climate, except that the severe turbulence has lasted a lot more than 4 months. Almost every forecast update has extended the projected duration of the recession, and the depth. The best current guesses anticipate no real recovery until 2010. That would make this downturn the longest since the 1930s. Figure 1: We are facing the worst recession in recent history, with a base case estimate of 5% decline in GDP GDP (Real) avg annualized % change '60 0% '01 '69 '45 48 '73 '08-09 (Base) '90 • Base case: -5% '08-09 (Downside) '81 '80 GDP, cumulative decline* • Down side: -7% '08-09 (Worst case) 53 • Worst case: -9% '57 -10 0 6% cumulative GDP contraction '29-'33 25 Months 50 * Total aggregate decline from maximum GDP expansion to the end of contraction Note: NBER recorded current recession as starting in December 2007; Projection updated as of March 23, 2009 Source: NBER; Bureau of Economic Analysis; "The Current Economic Recession: How Long, How Deep, and How Different From the Past?“, Marc Labonte; "Monetary Policy in the Great Depression: What the Fed did, and why", David Wheelock; Bain Analysis February 16, 2009 Page 1 Pulling Away | Managing and Sustaining Change As with the Vendée Globe, some companies in promising up front positions may end up trailing—or, in some cases, not even finishing—the competition. Figure 2 lays out the fortunes of public companies in the 2001 recession. Surprisingly, the chances of a market leader ending up trailing its competitors were greater than remaining in the lead. On the other hand, many companies in the second and third tiers of their industries moved up to the top. The reshuffling in the downturn period was much more significant than in normal times—in fact about twice as many companies in the group of top performers lost their leadership position during the 2001–2002 downturn compared with the subsequent boom period. Figure 2: In the last recession, more than 50% of top performers “fell” to the average and bottom buckets Number of companies Color represents 2000 performance 100% 80 782 782 Top 2002 performance Top 60 40 20 0 Average Average Bottom Bottom 2000 2002 Source: Sustained Value Creator Database/Worldscope; Bain Analysis Much of this share change happened toward the end of the downturn, when healthier companies started taking steps to gain altitude faster than their competitors, or where investments sustained through the downturn started to pay off in improved customer revenues. That is what makes the end of a downturn an excellent time for companies to be thinking about performance improvements and preparing themselves to gain position in the recovery. Supply chain improvements are powerful ways to make gains both in the short term and the long term. Since a huge amount of cost and capital is usually tied up in supply chain activities, any improvements drive cash savings in the short Page 2 Pulling Away | Managing and Sustaining Change term. At the same time, leaner supply chains should lead to faster growth later due to better in-stock positions and less diversion of potential growth capital into unnecessary inventory and facilities. Hard to Improve Obviously, a company must know what to attack in order to make gains, and most supply chain executives probably have a good idea about areas where savings need to come from—if not, 6 to 8 weeks of diagnostic work usually can flag the biggest opportunities. A less discussed but often harder problem for many supply chain leaders is capturing the savings they have identified. In one survey, executives reported that their average cost reduction project only returned 56 percent of the estimated savings, a pretty disappointing statistic. Most executives say the savings estimates up front were fine. They blame the gap on a failure to execute the required changes. Figure 3: Most change initiatives fail to achieve the results identified upfront Analysis of change initiatives shows that most fall short of achieving target results Percent of identified full potential actually achieved Implementation shortfalls are the main reason initiatives fail to reach targeted results Reasons for not achieving full potential 100% 100% 80 80 60 40 56% Implementation fell short 60 40 Opportunity not pursued 20 0 20 0 Opportunity smaller than believed Note: N=96 Source: Bain analysis Even when companies manage to implement some changes, the biggest challenge remains: making them stick. The CFO at one large company kicked off a recent efficiency project saying, “We’ve had three major efficiency programs in the last 10 years. Each was ‘successful.’ In fact, if you added up the claimed savings, our company would have negative costs. But our costs are higher than Page 3 Pulling Away | Managing and Sustaining Change ever.” Can supply chain leaders take steps to make improvements stick, instead of seeing excessive inventories, out of stock items and costs creeping back? There must be, since some companies are able to hold onto their winnings and deliver impressive gains, year after year. Their reward is improved performance that far surpasses gains by the average company. Not 5 to 10 percent better performance, but 50 to 100 percent better. In fact, we have found in almost every industry at least one runaway supply chain leader—a company that has opened up an overwhelming gap in performance versus their average competitor. The figure below highlights standout examples in inventory conversion. Figure 4: Most industries have a runaway performer Inventory conversion period (days) Runaway performer 100 Sector average 89 78 80 72 60 53 37 40 57 48 32 31 23 21 20 9 0 Dell Cisco Target Whole Foods Food Computer Communication General hardware equipment merchandise retail average average average average CVS Drug retail average PACCAR Construction and farm machinery average Note: Inventory conversion period = inventory/(COGS/365); Based on Bain benchmark database of ~1000 US companies. Sector average does not include the “best in class” benchmark (e.g.: Computer HW average does not include Dell) Source: Company financials; Capital IQ 2008 data Three Strategies for Managing Change and Pulling Away Without pretending to capture every action that helped these companies “pull away” from the industry average, here are three things we have found to be important: 1. Set improvement targets that are both competitive and strategic An amazing number of companies set fairly arbitrary performance targets each year. Maybe they are based on percentage improvements over last year’s Page 4 Pulling Away | Managing and Sustaining Change numbers. Or, they pick a goal that sounds ambitious, but essentially is pulled from thin air, such as double-digit revenue and earnings growth. That doesn’t work in sports competitions like the Vendée Globe, and it doesn’t work particularly well in business either. Such targets are often demotivating if leaders can’t provide context on why they are necessary or should be achievable. Moreover, if they are not anchored in competitive and external realities, organizations can mistake forward progress—or partial success—for victory. Planning to pull away from the pack requires a different approach—knowing your competitors and setting targets based on external performance standards and a clear view of what has to be achieved to beat competitors. Two highly effective tools can help set these targets: the experience curve and returns earned relative to competitive position. The experience curve tracks improvements in cost performance, over time and relative to total units produced. Bain has found that in almost every industry, competition drives down inflation-adjusted prices and costs every year. Two classic examples are shown below. Figure 5a: Experience curves can be used to set realistic targets US DRAM example Figure 5b: Understanding changes to the experience curve helps to keep ahead of competitive trends WIRELESS OPERATOR example Price per MOU DRAM Price per bit (2005 Millicents) $4 100 10 15% price reduction for doubling of MOU 85 Slope = 57% R² = 0.96 1983 1987 86 88 89 87 1988 1985 1 84 2 90 91 1 1990 93 92 1993 1992 2 Players 0.5 94 95 96 97 1996 0.1 38% price reduction for doubling of MOU 98 99 00 1998 0.01 0.001 0.01 0.2 2000 2002 0.1 1 10 100 01 6 Players 2004 1,000 10,000 0.1 100 200 500 1,000 2,000 5,000 10,000 20,000 02 50,000 200,000 1,000,000 100,000 500,000 2,000,000 Cumulative minutes of use (MOU) in millions Cumulative Experience (Cum. Bit Volume 10^15) Source: IC Insights (2004); ICE Status (1992) Note: R squared is 98% for 1984-1997 and 96% for 1997-2001. Source: Analyst reports As a manager, if you collect this information on your own industry, and assess your company’s rate of efficiency gains versus the industry trend, you will be able to set targets that are both realistic and aggressive enough to keep up with or beat your competitors. This approach can be used to set goals for inventories (days of inventory on hand), asset productivity, logistics spend per unit, and many similar supply chain metrics. For instance, one of our clients, a market leader in specialized apparel, projects industry cost and price declines and sets targets for sourcing costs to stay ahead of this competitive trend. Plotting returns earned versus your market position is another way to use external competitive data to set performance targets. Returns earned need to be in line with relative scale. In most industries, relative market share—your market share divided by the share of your largest competitor—has a high correlation Page 5 Pulling Away | Managing and Sustaining Change with profitability. (It is important to define markets properly; for retail and distribution, it usually is share by city, while for manufacturers it may be national or global market share. See the figures below for examples.) Figure 6a: Returns vs. Relative Market Share analysis helps determine “should be” performance level in line with your market position High Figure 6b: Example of Returns vs. Relative Market Share analysis US FOOD STORES example EBIT Margin 2 1 Over-performers (leaders or followers) In-band leaders 15% Company 10 10 Company 9 Company 4 3 In-band followers Returns earned 4 Company 11 5 Company 6 Below-band leaders Company 7 Company 8 Company 2 0 Company 5 5 -5 0.1 Distant or below-band followers Low Weak Relative Market Share Strong $20B Sales Company 3 Company 1 0.2 0.5 1 2 5 Sales Weighted Local RMS for U.S. retail grocery (2006) Note: Includes all major public grocery chains except for one that does not break out its pure grocery EBIT. Company 2 EBIT margin is estimated. Knowing your company’s relative market share should give you a good idea of your performance level target. Such target setting keeps market leaders honest and helps them avoid the trap of satisfactory underperformance. Once these strategic targets are set, we have found it is critical to detail three to five initiatives that allow a company to move from point A to point B. The key is to keep it simple: limit the number of initiatives and communicate them, again and again, across the organization. Then typical goal deployment tools can be used to implement them in specific functions and assign direct accountability to individual managers for targeted performance gains. Functional staff should find these goals much more meaningful, since they are based on hard facts about the market and competition, not just management intent. 2. Use left-brain tools to spot right-brain barriers For the supply chain, a major challenge in managing change is maintaining both momentum and focus among individuals who are scattered throughout the company. After all, most major supply chain initiatives affect distribution, sourcing, finance, marketing and sales, manufacturing, and IT at a minimum. Many critical staff members don’t report to the project sponsor, and efforts to win hearts and minds and manage details can quickly consume a normal work schedule. Obviously it won’t work to spread leadership time evenly. But it is essential to do more than just putting out the biggest fires and dealing with squeaky-wheel employees. Some employees may not speak loudly, but may passively undermine progress. And some have more of an impact on gains than others, making their commitment to change more important. Page 6 Pulling Away | Managing and Sustaining Change To help our clients, we have created some “left-brained tools” to figure out which parts of the organization will have the hardest time changing. Executive sponsors can then focus their leadership energy in these areas. We call this a “readiness to execute” diagnostic. Think of it as creating the equivalent of some good sailing charts, instead of simply setting sail and dealing with whatever you encounter. The diagnostic accomplishes two things: on the one hand, it surveys a range of current employees on such issues as perceptions, concerns and beliefs, and it plots the results to flag major areas of disconnect with top management. Those areas require more substantial intervention. On the other hand, analysis is done to understand who is forced to change more, based on factors like level of compensation change, shift in their time allocation or changes in their performance metrics and standards. People that are affected the most by these changes are the most likely to resist. The same approach often uncovers corporate cultural challenges that affect communications content and strategies. A sample output is included below. The core idea is to not leave culture and motivation issues to the corporate psychologists, but instead to use objective facts to measure where the risk is greatest, so managers know where their time will have the highest performance payback. Figure 7a: Sample readout of a “Readiness to Execute” survey—comparison to external benchmarks Benchmark: High performers n=151 Benchmark: Low/average performers n=610 Company X average responses Under- Figure 7b: Sample readout of a “Readiness to Execute” survey—internal distribution of responses Out- 1 performing 2 Satisfactory 3 performing 4 Clarity on priorities and principles Priorities “We have clear roles and authorities for critical decisions” % of respondents Cohesive leadership team aligning full org Clear roles & authorities for critical decisions 100% 83 Software Roles Decision disciplines that make roles work 75 Effective, integrated management processes Processes Superior operational and support processes People Right people in right jobs – will and skill Objectives & incentives focused on performance Culture Winning culture – values and behaviors 50 25 Hardware 56 Agree 0 -25 Individuals who personally engage Structure 67 Strongly agree Structure aligned with sources of value -50 Detailed structure as lean & simple as possible -75 Disagree Strongly disagree -17 -33 Executive team -44 Directors Managers Note: High performers = top quintile of ‘decision multiplier’ scores Source: Bain/eRewards decision and org effectiveness survey 2008 (n=761); Client survey (n=20) 3. Decide “who decides” Most supply chain leaders hate bureaucracy, but they live with it every day. Simple decisions like whether to add or remove a SKU, what products to stock where, or setting production forecasts can paralyze progress. This decision congestion is one of the key reasons change initiatives have such a low rate of success. For example, a supply chain manager in one Global 50 company complained about a non-decision regarding a new replenishment system, estimated to have a three-month payback. After a year of discussions, he threw up his hands: “I can’t even get someone to say ‘no,’” he said. “I spend all my Page 7 Pulling Away | Managing and Sustaining Change energy debating, and none of it doing.” He ultimately left to take a job with a more dynamic company. One of the best tools used to zero in on this problem and create higher-yielding change programs is a decision management tool we call RAPID. The idea is to clearly map out who plays what role in each critical decision and use that to enable swift decisions, without endless debates, second-guessing or pocket vetoes. It determines the captain of the boat, so to speak, but in a more nuanced way that deals with the different teams needed for different problems. To try this approach, start by writing down 10 to 20 of the critical decisions that have to be made on a regular basis and that are fundamental to supply chain performance. It can include questions like: “Should we introduce a new SKU? What is our forecasted volume for next month? or What level of product Y inventory should I carry in facility X?” Then, use a grid to identify all the management positions that touch that decision and assign a letter indicating their role today. R = recommend, A = approve/veto, D = decide/choose, I = inform, P = perform/execute after the decision. (The figure below illustrates an example). Most companies find that the RAPID process is a stunning way to highlight the problem we call “Who has the D?” On many important decisions, there typically is either no one with formal authority to decide, or more often several people who each think they get to choose and who end up interfering with each other. The result is endless meetings, decisions that are delayed or don’t stick and a slow pace of change. The solution is simple: Rewrite the map, and for every decision, make sure there is no more than one D and no more than one A. Eliminate any unnecessary input. Then publish this document and distribute it throughout your organization. Page 8 Pulling Away | Managing and Sustaining Change Figure 8: Clarifying decision-making roles materially improves execution capability Drivers of decisionmaking complexity RAPID roles and responsibilities n6 n7 Pers o I I D/A I D R 2. Next month’s R I D D I I 3. carried in Facility X? R I D A A I I 4. Vendor selection? R I A A I I I/P forecasted volume? Level of inventory Pers o Pers o 1. Introduce new SKU? Sample decisions: Pers o Pers o Pers o n4 n1 ILLUSTRATIVE • 1 & 2: Multiple Ds: Too many felt they had decision rights Recommend Approval Perform Input Decide D n5 I Pers o P n3 A n2 R • 3: Too many As: Veto rights across multiple groups for each decision • 4: No D: Nobody was taking accountability for the decision The positive reaction that many companies have to this process is amazing. They find that suddenly meetings disappear as large groups are pared down to the few who really need to be involved in key decisions. Those who are assigned the “D” (decision authority) know it and can act quickly without worrying about being second-guessed. One client told me that the single-best thing that came out of a project together was the concept of RAPIDs, which dramatically accelerated actions and, frankly, took a lot of pointless meetings off of his calendar. Conclusion Over the next year or two, companies will face substantial challenges. As the recession deepens, the battlefield will shift from great ideas and strategies to strongest execution. Like competitors in the Vendée Globe race, some companies accustomed to swiftly navigating calmer waters won’t rise to the occasion. They’ll fall back in the pack, be acquired or face bankruptcy. But companies that are able to stay the course will be equipped with action plans grounded in practical targets and tools to overcome key obstacles and inefficiencies. Being well prepared not only improves their chances of making it to the finish line, it allows them to emerge from the turbulence stronger than ever. Page 9 Pulling Away | Managing and Sustaining Change Miles Cook is a partner at Bain & Company in Atlanta and a leader in the firm’s Global Performance Improvement practice. He can be reached at miles.cook@bain.com. Suggested additional reading The Breakthrough Imperative; How the Best Managers Get Outstanding Results (HarperCollins, 2008), by Mark Gottfredson and Steve Schaubert, Bain & Company Who Has the D? How Clear Decision Roles Enhance Organizational Performance, (Harvard Business Review, 2006), by Paul Rogers and Marcia Blenko, Bain & Company Page 10