Using Historical Sources: A Guide for Students

advertisement

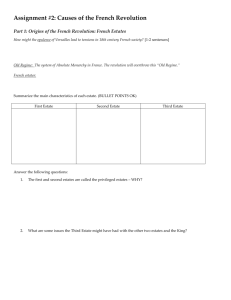

Using Historical Sources: A Guide for Students With particular reference to The French Revolution and the Tableaux de la Révolution held at Waddesdon Manor Andrew Holland in conjunction with Katherine Astbury University of Warwick 1 Contents 1 Introduction 2 The Nature of Sources What is a historical source?.....................................................................3 Categorising sources…………………………………………………………………………….3 The Variety of Sources………………………………………………………………………….5 The Hierarchy of Sources………………………………………………………………………6 3 The Critical Analysis and Evaluation of Sources Authenticity………………………………………………………………………………………….7 Provenance…………………………………………………………………………………………..8 Purpose…………………………………………………………………………………………………9 The Strengths and Limitations of Sources as Historical Evidence…………14 Appendix 1…………………………………………………………………………………………………….15 Appendix 2…………………………………………………………………………………………………….15 Important Please not that this is exemplar material and represents work in progress. The final publication will incorporate specific sections on the nuances in dealing with pictorial sources. It will also include a much greater range of student activities that will partly link to the requirements of the major awarding bodies. The exemplar material can be trialled by schools and colleges with their students but it is part of a bigger package that is under copyright to the author. © Andrew Holland 2012 First Edition published in 2012 by the University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL 2 Using Historical Sources: A Guide for Students Introduction This guide is designed to help you tackle different historical sources in ways demanded by various awarding bodies and educational institutions. The focus is on: a) b) c) d) how to interpret sources i.e. how to make sense of the content of sources how to compare and contrast sources i.e. to establish degrees of corroboration how to interrogate sources to establish levels of validity and reliability how to utilise a range of sources in conjunction with contextual knowledge to solve historical problems. Before covering each of these task areas it is worth reflecting on the nature of historical sources. Different sources have different features which can determine their strengths and limitations as historical evidence. The Nature of Sources What is a historical source? A simple definition would be that a historical source is written or non-written information produced by a variety of people from the past. People leave information in a variety of formats including letters, diaries, minutes of meetings, official documents, paintings, cartoons, newspaper articles, artefacts, buildings and the landscape. The latter is a complicated type of historical source; much of the landscape has not changed a great deal over time. Where landscape change has occurred it has not always been the result of the actions of people. The natural elements play an important role in determining the environment we live in. However, generally, most of the sources historians are interested in are the products of the intentional and/or unintentional acts of human beings Categorising sources 1 Primary source A primary source is one which dates to the period of time that is being studied. It is sometimes referred to as ‘first-hand knowledge’, ‘eyewitness account’ or information that comes ‘straight from the horse’s mouth’. Primary sources are often considered to be the most trustworthy of all sources. After all, if someone produced an account of an event having been there to witness it this must surely make it a valuable and reliable source for the historian. 2 Secondary source A secondary source is one which is produced some time after the period of time that is being studied. It usually comes in the form of a textbook, monograph or academic article. As the writer relies on other, usually a mix of primary and secondary, sources and did not witness events first hand, secondary sources are sometimes deemed less useful and reliable than primary sources. 3 On reflection this seems to be a rather weak way of categorising sources and assessing their utility. Explain why this might be the case in the box below According to the historian Marwick primary and secondary sources are related by the process of historical research (some might argue that history IS the result of research). For Marwick research means ‘diligent and scholarly investigation in all the available primary and secondary sources, conducted not merely with the aim of ’making a book’, but in order to extend human knowledge in a particular area’ . Thus, it is not that one type of source is more reliable than the other that is important but the complementary relationship between them. Having said this, it is the researcher and/or historian who engender this relationship. The standard view is that historians firstly survey the secondary material on a given topic before embarking on the research of primary sources. This enables the historian to interpret primary source material mainly by placing it in context. It also distinguishes what Marwick has called ‘pop history’ from academic history. Pop history-the communication of knowledge, gained by other historians, about the past in a popular way Academic history-the exploration of the unknown past so as to add to the sum of total knowledge and by using primary sources So, in summary it is important NOT to fall in to the trap of arguing that when a source is primary it must be more reliable. Added to this is the problem of assessing whether in the first place a source is primary or secondary. For example, is the Bible a primary or secondary source? The Variety of Sources There are many different types of primary source. How many can you think of? List them in the box below. 4 Compare your list with that provided in Appendix 1. What do you notice? You may have more or less than what is in the appendix. That does not matter. What is significant is that: There is a huge range of primary sources (what is in the appendix is not an exhaustive list). Anything that emerged during the period in the past that we are studying could be called a primary source. If Marwick’s definition of research is valid then studying all of the relevant and available primary sources for a given period is problematic. A certain amount of selectivity has to occur which in turn poses questions about whether history is simply the CONSTRUCT of the historian. There is a difference, often blurred, between a SOURCE and TECHNIQUE e.g. between how an individual looked and how a photographer made them look; between how an event took place and how an engraver used his/her skill to depict that event; between the words used to denote people and places and philology. It is possible and maybe desirable to systematically categorise primary sources. From this a sense that some primary sources have more purpose than others emerges. In other words, there is considered to be a hierarchy of primary sources. How useful is the concept of hierarchy in this respect? The variety of primary sources enables historians to dig deep to find answers to questions that mount up as research progresses. The depth and breadth of sources also facilitates the process of corroboration, a necessary requirement for establishing the reliability of sources. But, sometimes a range of sources does not exist on a particular topic or the range is disrupted and incomplete. In other words, the historian hits a brick wall and may have to resort to guesswork to fill in some of the gaps in the story. Once again, this has implications for deciding on what actually constitutes history. The Hierarchy of Sources It is fairly common place for some historians to rank primary (and secondary sources) in order of importance. Such importance is often linked to how fundamental and detailed sources are. Thus, for example, official written sources are classified as being above non-official unwritten sources in terms of significance. Marwick and others tend to use the following hierarchy as framework for reference. CATEGORY OF PRIMARY SOURCE COMMENT Manuscript sources are more important than printed sources (and more ‘authentic’?) A document written in the ‘hand’ of someone alive in the period being studied. Fine but hand-written manuscripts were often copies of earlier documents. They may not be exact replicas of the originals. 5 Written sources (manuscript and printed) are more important than ‘other’nontraditional sources Archaeological artefacts, pictures, film, oral testimony etc. are all interesting and useful in their own right but are often useless without contextual knowledge gained from written sources. True but much depends on the time being studied and also the topic. Official documents are more important than private ones In this respect official means pertaining to government i.e. those in authority/power. Governments have come in different shapes and sizes which has influenced the type of ‘official’ documentation they have produced. Also, there is something of a crossover between official and private; for example, government ministers often kept non-official diaries and wrote private letters which revealed much about political developments. How would we rank these in terms of historical importance? Sources that are mostly primary but contain aspects of secondary sources Most obviously these are contemporary histories (i.e. histories of events written as they are actually happening or very shortly afterwards), autobiographies and studies based solely on the development of a particular argument (a polemic). Such sources are problematic in that it is difficult to discern opinion from fact and judgement. The ‘intentional record’ is mixed up with the ‘unwitting testimony’. For example, Thomas Carlyle’s ‘The French Revolution’ tell us as much about Carlyle’s own political stance as it does about the events in France in the 1790s. 6 The Critical Analysis and Evaluation of Sources Authenticity Historians will often want to establish how authentic or genuine a source is before proceeding to analyse and evaluate it as evidence. The work of historians in the past (or HISTORIOGRAPHY) is littered with examples of where a lack of authenticity has been established resulting in the discrediting of the findings and judgements made by the historian. The classic, fairly recent, example of this was where the Oxford academic Hugh Trevor-Roper failed to check on the authenticity of the so-called Hitler Diaries. Once the diaries were proved to be a fake, he never recovered his reputation as one of the most eminent historians of the twentieth century. Most of the time young historians i.e. those at school/sixth form/college ( and even undergraduates at university) will not be involved in the authentication of sources. They are given sources to handle which have already been validated. There may be occasions though where an independent study, extended essay or dissertation is being carried out which does require certain sources to be authenticated. This would require two methods to be adopted, one of which is likely to require the help of a specialist. 1 INTERNAL checking After time historians begin to recognise that certain types of source have their own peculiar set of characteristics. Categories of written documents may be produced using a particular style of language, a regular type of ink and paper or in a special typeset. They are likely to be set out in a regular structure with some kind of added, official recognition e.g. a royal seal; government departmental stamp; official signature. This is also true of unwritten sources such as pictorial sources and objects which will have their own set of characteristics. Internal checking has been greatly aided by advancements in science which now allow us to examine whether paper, ink etc. can be dated to the period of time that the document etc. seems to originate from. 2 EXTERNAL checking This is where information contained within a source is checked against information that has already been established as reliable and that has been gained from a range of other sources. The basic facts relating to when?, who?, and where? Are usually focused on; it gets trickier to carry out external checks on explanation based information (why? and how?) as this often overlaps with the motives /intent of the author of the source. Presenting the ‘facts’ is easier than revealing an interpretation of an event or actions of an individual in the past. However, if external checks reveal discrepancy this does not necessarily mean that the source under scrutiny is not authentic. It could mean that the established ‘story’ based on other supposedly authentic sources needs to be re-evaluated as the newly discovered source might actually contain the correct version of events. Provenance Knowing about the ORIGIN or provenance of sources can help us greatly in our critical analysis and evaluation. For school/college pupils and students such information is often pre-supplied by teachers 7 and awarding bodies (within examination papers that test skill in the handling of sources). Awarding bodies usually provide information about provenance within a GOBBET sited at the top of the source based examination exercise. This is likely to supplement other information provided at the end of each source. Pupils/students are strongly advised to take note of this information and use it when answering the questions they have been set. It is often neglected but can help greatly when it comes to both interpreting and analysing each source. You will see that with each exercise you carry out using material from the Waddesdon collection of prints on the French Revolution a relevant gobbet is provided at the start. The origin of a source relates to: WHO produced it (authorship); what was their role/status in society? E.g. rich person/poor person; male/female; old/young; black/white. WHEN it was produced (date/time) e.g. then/now. WHERE it was produced (region) e.g. West/East; North/South; rural/urban; France/Britain. HOW the source was produced (method). In the box below explain how knowing about the provenance of a source can help you make balanced judgements about the usefulness and reliability of sources. PROVENANCE FACTOR COMMENT ON IMPORTANCE Who? When? Where? How? Purpose When talking about the purpose of a source we interested in the motives/intentions of the author. Sources of information exist for a number of reasons. As hinted at in the section on hierarchy, sources can be produced intentionally or unintentionally to provide a record of the past. This point applies to both primary and secondary sources. 8 Below is an exemplar list of sources and the likely motives behind their production TYPE OF SOURCE (and provenance) LIKELY MOTIVE A book written by Edmund Burke titled Reflections on the Revolution in France, 1790 Burke wrote this book at the time of the Revolution to express his disgust at the actions of the revolutionaries. He was particularly critical of the way old institutions and traditional customs were destroyed. Burke saw the need for reforms but thought revolution was far too drastic a way for change to occur. He also thought that the French Revolution would have a negative impact on Britain. A letter written by Marie Antoinette to Mercy-Argenteau, 3 February 1791 Marie-Antoinette wrote this letter to her mentor, the former Austrian ambassador, to express her ideas on how Louis XVI should respond to the Revolution. She believed for the need to ‘pardon the people which (sic) has only been led astray…except from the pardon the revolutionary leaders…’ Historians often refer to this source to show that MarieAntoinette was displaying independence of thought and that she was doing her best to influence how Louis should tackle the issues facing the monarchy. However, Louis’ 1791 declaration was quite different from the proposals outlined by his wife. King Louis XVI’s declaration on leaving Paris, 20 June 1791 This was drawn up by Louis XVI in the months before he left Paris for Lorraine. The declaration seems to have been made to express Louis’ feelings about his acceptance of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the role of the Constituent Assembly. In general, it is a set of complaints that highlights Louis’ anger over the loss of his executive powers. 9 Prints depicting events during the French Revolution There are many different types of prints depicting events during the French Revolution. Many of them are satirical in nature and use humour to criticise those who held positions of authority, the wealthy and those who attempted to obstruct the course of the revolution. Thus, they are mainly forms of protest although they also reflect more generally the ideas, values and beliefs of the authors. Now complete the following table making comments about likely motives for the production of the pictorial sources listed in the left column. To do this you will need to: a) Access the Waddesdon Collection of prints on the French Revolution to be found at http://collection.waddesdon.org.uk/advancedSearch.page.do?collection=28 b) Search for each print using the title and accession number c) Use the commentary material that goes with each print. TYPE OF SOURCE (and provenance) LIKELY MOTIVE Title: ‘The Patriotic Dentist’ Artist or maker: Unknown Date: 1790 Place of Production: Paris, France Accession number: 4232.2.4.2 See commentary for more information on provenance and context Title: 'Pas de Deux Between a Jacobin and a Feuillant' Artist or maker: Unknown Date: January 1792 Place of Production: Paris, France Accession number: 4232.2.6.7 See commentary for more information on provenance and context 10 Title: a Woman Being Punished for Showing Disrespect to Necker's Portrait Artist or maker: Unknown Date:1789 Place of Production: Paris, France Accession number: 4232.1.19.40 See commentary for more information on provenance and context Notice how knowing about the provenance of a source is likely to be helpful in establishing the motive of the author. Often, though, it is difficult, especially with secondary sources, to establish the purpose behind the sources. Historians are motivated to write texts and articles for a variety of reasons. These may include: The need to promote a set of arguments and findings The desire to write popular history (and to therefore make some money!) The need to publish because the institution the historian works for is putting them under pressure to do so More generally, writers of secondary works are consciously or sub-consciously influenced by Their gender Their race and/or cultural background Their socio-economic status (past and present) Their age Their geographical location The time in which they are writing For students of history it can be a frustrating task to answer questions about the usefulness and reliability of sources when it is not obvious that the author may be taking a particular APPROACH towards the research of a particular historical topic. In this case a number of tasks can be carried out: 1 Basic internet research can be done on the background of historians 2 Dust jackets and the first pages of books often contain biographical material on authors 3 If the author has passed away, obituaries can be found, again on-line, which provide invaluable information about the approaches taken by authors to their work. Read the following obituary of the populist historian Christopher Hibbert and page 11 from his book ‘The French Revolution’ (see Appendix 2) What kind of approach do you think Hibbert adopted when writing about The French Revolution? 11 What aspects of Hibbert’s life were likely to have influenced the way he interpreted and approached his study of historical characters and events involved in the French Revolution? Explain your observations. How far does the extract from Hibbert’s work shown in Appendix 2 support the observations you have made about his interpretation of and approach to studying the French Revolution? Christopher Hibbert: Popular historian whose favourite subject was Italy by Francis Sheppard Source: The Guardian, Tuesday 27 January 2009 It is a well known fact that Christopher Hibbert, who has died aged 84, was the best loved and most widely read popular historian of the latter part of the last century. "It's a well known fact that ..." was how he would start, and embark on some wildly exaggerated and embroidered story to the delight of his friends and family. "No, really! An extremely well known fact," he would insist. Hibbert was not a specialist; his oeuvre encompassed topics ranging from the Battle of Agincourt (1964) to The English: a Social History 1066-1945 (1987) to a biography of Benjamin Disraeli (2004). His fourth book, The Destruction of Lord Raglan (1961), won the Heinemann Award for Literature. He had more than 50 books published and was, said the Times Literary Supplement, "perhaps the most gifted popular historian we have". His favourite subject was Italy. He wrote Benito Mussolini (1962), Garibaldi and his Enemies (1964), Anzio and the Bid for Rome (1970), The Rise and Fall of the House of Medici (1974), biographies of Rome (1985), Venice (1988) and Florence (1993). Throughout his career, his works, extensively researched, were always written in a spidery longhand, which would later be transcribed by a stenographer. One such, a woman who had led a somewhat sheltered life, was dealing with a racy passage in his The French Revolution (1981). She stopped typing and turned to her husband: "What's pornography, pet? Because I think I'm typing it." Hibbert, though, was never sensational for sensation's sake. He wrote in a careful, measured and meticulous style, not seeking to impose his personality on his prose, preferring to present the facts to the reader, to set his story out before them, rather than to embellish his research with supposition, theory and conjecture. He was born in Enderby vicarage, Leicestershire, where his father was the vicar - and later canon. Hibbert was the second of three children, and christened Arthur Raymond. He went to Radley school in Oxfordshire and later Oriel College, Oxford, but reading history was interrupted when he was called up. He joined the London Irish Rifles in 1943, where, on his first day in uniform, he acquired his new name. His regimental sergeant major caught sight of the 18-year-old Hibbert, who looked even younger than his years: "What have we got here? Christopher fucking Robin?" The name Christopher stuck. He served as a London Irish Rifles infantry officer with the 8th Army during the Italian campaign, being awarded the Military Cross during the attack on the German fortification on the River Senio during the winter of 1944-45. He was wounded twice while fighting along with the partisans during the battle of Lake Comacchio in April 1945. He then moved on to become personal assistant to General Alan Duff at allied 12 force HQ in Italy. In a field hospital in Italy, he met the actor Terence Alexander - most famous for playing Charlie Hungerford in the TV series Bergerac. Hibbert was in the next bed to a German soldier. At least one nurse neglected to dress the German's bandages. Hibbert and Alexander tenderly did so, on the grounds that the war was hardly this individual's fault, any more than it was theirs. Back at Oxford, Hibbert met Susan Piggford, a fellow undergraduate, who was reading English at St Anne's College. She was the love of his life and they married in 1948. After graduating, he began a career as a land surveyor (1948-59) which he did not greatly enjoy. He wrote in his spare time, and, became television critic of the now defunct Truth magazine. His wife supported his wish to make a living out of writing even though money would inevitably be tight, but she may have cut short his career as a fiction writer. Hibbert had written a radio play about adultery. Sue typed it for him but omitted the raunchy and saucy parts on the grounds that it would upset his parents if broadcast. The play was declined by the BBC. It was only some time later that his wife confessed to that; but by then, his career as a historian had started. His first book, The Road to Tyburn (1957), was accepted by Longman, Green. There his editor was John Guest, who continued to be Hibbert's editor until his death in 1997. Then came King Mob (1958), on the Gordon riots and Wolfe at Quebec (1959). It was then that he became a full-time writer. In 1971 he produced The Personal History of Samuel Johnson. Johnson was one of his heroes, and in 1979 he edited Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson. The following year he was asked to become president of the Johnson Society. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, he was awarded a DPhil by Leicester University in 2000. He enjoyed gardening, bringing home mud-caked vegetables for his wife from his "allotment" - a big corner of a friend's garden - the Simpsons and Coronation Street. The house was crammed with cats when his family was growing up. He was not a connoisseur of film, but liked the adventure of going to the pictures and loved taking his children to appallingly unsuitable films. He enjoyed anything from westerns to Carry On and was proud that he once helped Sid James park his car in Jermyn Street. Above all there was his family, and friends, for whom he would give big parties with big drinks. Hibbert died in Henley-on-Thames, his home since 1954. He had had just over 60 years of an extraordinarily happy marriage. He was described by JH Plumb as a "writer of the highest ability", and by the New Statesman as a "pearl of biographers". He could not write a dull word if he tried, suggested the Sunday Times. He was uxorious and philoprogenitive, generous, loving, and loved. He was devoted to his children, James, Tom and Kate, and to his three granddaughters, as they were to him. Christopher (Arthur Raymond) Hibbert, historian, born 5 March 1924; died 21 December 2008 The Strengths and Limitations of Sources as Historical Evidence 1 Validity Historical sources are said to have ‘strength’ if they are valid i.e. if they are relevant to the topic being researched and if they can be validated (seen to make sense; are logical). This is obviously linked to reliability. 13 2 Reliability If sources are reliable then they are considered to be trustworthy i.e. they are speaking the ‘truth’ (whatever that might mean!). The more reliable a source, the stronger its utility. But how are validity and reliability established? Part of the answer to this has already been hinted at. The answer is by looking at: The nature (type) of the source The origin of the source The purpose of the source It is also important to be able to interpret the language of the source both in terms of what is explicitly and implicitly communicated. Students often find it difficult to interpret written sources if they are produced in a code of language that is not familiar to them. The main solution to this is to continual practise reading, annotating and analysing such sources until a familiarity with the language develops. Common sense will also tell you that ‘big words’ should be researched using a dictionary. Also, it is really helpful to read contextual material as this will help with interpretation. Implicitly communicated messages in sources can usually be untangled by paying attention to the style of language used and the general tone of writing. How emotive is the writing? How reasoned is the writing? How much is emotion mixed with reason? It is also helpful to analyse text in terms of FACT, OPINION and JUDGEMENT. Fact-something that is definitely the case, that can be proven to be true by appealing to a range of evidence Opinion-a personal point of view not necessarily based on fact Judgement-usually a decision made by a person that is based on fact. Appendix 1 The following list provides some idea of the range and diversity of primary sources used in historical research. It is an edited version of a list taken from Arthur Marwick's Introduction to History (Open University, 1977): 1.Records of central government: e.g. laws, charters, dispatches; Parliament, Council, Cabinet; tax and fiscal records; local records: parish registers, police files, marrorial courts, electoral registers; records of institutions, societies, political parties, trade unions; private business or legal records, company archives 2.Official surveys and reports (from Domesday Book to recent Royal Commissions). 3.Chronicles and histories: e.g. monastic, civic, institutional. 4.Family and personal: e.g. private letters, diaries, journals. 14 5.Media records: e.g. newspapers, pamphlets, treatises, cartoons, posters, advertisements, films, videos. 6.Archaeology: e.g. coins, buildings, inscriptions, costumes. 7.Literary and artistic works: e.g. novels, plays, poetry, painting, sculpture. 8.Others: e.g. maps, photographs, oral testimony, folk songs. Appendix 2 ‘This is a narrative history of the French Revolution from the meeting of the Estates General at Versailles in 1789 to the coup d’etat of 18 Brumaire which brought Napoleon to power ten years later. It concentrates on events and people rather than ideas, particularly upon those journees (days of popular action) which helped to decide the course of the Revolution and upon those men and women involved in them. It is written for the general reader unfamiliar with the subject rather than the student.’ P.11 15 French Revolutionary Prints: a Guide for Students By Claire Trévien, University of Warwick, August 2012 What is a print? At its most basic, a print designs the process of transferring ink from a prepared surface (a metal plate for instance) to some other material (such as a sheet of paper). A carved potato dipped in ink and pressed against some paper would count as printing for instance. The act of pressing the plate into paper leaves a mark of the outline of the plate into the paper, which is called the platemark. Different Types There are two main types: relief printing and intaglio. Most Revolutionary prints are intaglio. Intaglio is an Italian word for engraving, and within it there are many different types of techniques which will be outlined below, mostly using copper plates as their base. Relief printing is when you raise the surface; intaglio is when you carve into the surface. A rubber stamp is a type of relief printing for instance. It's less accurate than intaglio, more messy. Intaglio on the other hand allows for many different techniques; at its most basic, varying the depth of lines within the plate can subtly vary the shading of the image. Types of intaglio Engraving: uses a burin (a tool with a sharp V-shaped point) to carve into the copper plate. This creates a very steady line, and requires great skill. It is often the tool used for texts under the images. Etchings: Most popular Revolutionary prints are etchings. Instead of using a burin, the copper plate is heated with wax rubbed across its surface. Once cooled, the craftsman etches into the wax, exposing the copper. The plate is then immersed into acid (for varying lengths of time depending on effect wanted). The wax is impervious to acid. What this technique allows for is a much more fluid style than engraving. It looks like a sketch and is generally less formal than engravings. In the more sophisticated prints, an artist would first etch the plate then engrave over it later, combining both methods. The next two techniques discussed are often added to etchings. Just as etching looks like a pencil, these two methods were also created to replicate other drawing and painting techniques. Indeed, unlike drawings and paintings they could be mass produced so the techniques could be used to replicate a famous painting for instance. Stipple engraving: This is a technique used to look like chalk or crayon. The effect is created thanks to an instrument called a roulette. This was a metal wheel with a variety on sharp points that could be rolled over the waxed copper plate. Later this evolved to the use of a mace-head, a tool you'd punch into the waxed plate. This can add a grainy texture to etchings. Aquatint: This reproduced the effect of a watercolour. Substances, such as resin, or asphalt can be applied to metal in two ways, the most common was to dissolve it in alcohol and pour this combination on to the plate. The other was to apply it as a dust, then burn it into the plate. Colour Most Revolutionary prints were hand-coloured after the image had been pressed. Occasionally you will find prints whose colours have been printed. One tell-tale sign of this is if you see multiple 16 plate-marks, one for each time the printer added coloured ink to the recesses of the plate. If the colour is uniformly applied with no white dots or shapes, then it is almost certainly hand-coloured. What do the names below the image mean? You will sometimes see directly below an image one or two names. The general convention is that the name on the left is that of the original artist (or designer) while the name on the right is that of the craftsman who created the printed image. The names are often accompanied by abbreviations that provide further clues. These are some of the most common: del. means 'drew', indicates generally that this is the name of the artist. exec. means 'struck out' or 'made', indicates either the publisher or the craftsman. fecit means 'made' or 'did', often used to indicate the name of the artist who also crafted it. inv. means 'invented', used to indicate name of original artist. sculp. or sc. means 'carved', and has variable uses. Generally provides a clue that engraving was employed, and often indicates craftsman. The Text If the letters are inverted that's almost certainly because the craftsman forgot that he has to etch or engrave his text in reverse into the plate so that it appears correctly on the sheet. Texts are generally engraved, unless they are very wispy and uneven, in which case it is probably an etching! Who produced these prints, and how were they sold? In Revolutionary Paris, prints were predominantly sold in the quartier Saint-Jacques, the left bank of the Seine near the Quai des Augustins, and the Palais-Royal. They were sold by street hawkers as well as in shops and stalls. A large portion of caricatures were anonymous and a larger amount still are without dates, making it difficult to contextualize conclusively a substantial portion of prints. However, some names of publishers re-occur on several prints such as Basset. It is also known that Villeneuve, who created many prints would sell these at Basset’s, which suggests that anyone who owned the means to create prints could do so at their own discretion and sell them through either a well-known channel, such as Basset, or through some less official stalls and hawkers. Who bought them? No known records have survived of purchases at Basset but we can determine through the prices, which occasionally appear on the prints, how affordable they would have been. Etchings are always cheaper than more sophisticated engravings as easier to produce (etchings could be created in a matter of days, engravings, particularly on a large scale, could take months). An etching would have been worth less than a third of a worker’s daily wage, so was not out of reach for a member of the working class. Some conclusions can be drawn derived from price: expensive prints would go to rich owners and sketchier and cheap caricatures would be bought by poorer members of the population. Nothing necessarily stops the reverse from having happened of course, poorer workers could have saved 17 up for particularly fine engravings, rich bourgeois could have a taste for caricatures. Print shops also had a system of loan, whereby you could rent a print to adorn your wall, making them more affordable. That they were bought goes without saying, the multiplication of publishers during the Revolution demonstrates an insatiable demand. An example: La Liberté (Waddesdon Manor, accession number 4232.1.76.156). If you look closely at this print, you can see that directly below the image there is some small text. It reads: ‘Dessiné par Boizot / Gravé par la Cne. Lingée fe. Lefevre’. This makes identification easier since they have not used obscure terms to indicate who did what. Boizot was the artist who designed the print (and is on the left as convention dictates) while Citizen Lingée (a woman, as indicated by Cne, short for Citoyenne) the wife of Lefevre, engraved it. Further down, below the title ‘La Liberté’ is some more text: ‘A Paris chez Basset, rue Jacques au coin de celle des Mathurins.’ which tells us that it is sold by Basset in his shop. If this print were adorned in someone’s home for instance, this would easily allow others to know where to purchase their own copy. What of the techniques used? This is sophisticated print utilizing more than one technique (the first clue of this is in the identification of everyone involved in its creation, demonstrating that it is a respectable print). The text is engraved, which you can tell from its controlled quality. The print itself is etched with stipple engraving. You can tell that it is stipple engraving being used rather than aquatint because of its grainy (rather than watercolour) effect. Finally, though it is hard to tell without a magnifying glass, this was printed in red, white, blue green and brown inks. Who do you think would have bought it? 18 The French Revolution and the Three Estates: an exercise in the interpretation of prints Study the print below and complete the tasks listed underneath. Waddesdon Manor Accession number 4232.1.25.50 The print is of an etching produced in Paris, France in 1789. The author is unknown. The print shows members of the Three Estates playing with a dice. To help you interpret the print and complete the tasks you will need to read: a) The background information on the Three Estates in box 1 b) The translations in box 2 of the text in the ribbons, banner and flag shown in the print Box 1: Background information on the Three Estates 19 In the eighteenth century French society was divided into three groups referred to as the Estates of the Realm. The first two estates were considered to be superior to the third; this caused relations between the states to become increasingly tense. The states were as follows: The First Estate. This consisted of the clergy and religious orders. By the 1780s the First Estate was being heavily criticised as a result of plurality and absenteeism, tithe issues, exemption from paying taxes and widening powers of censorship. The Second Estate. This consisted of the nobility (c350, 000) of different ranks. The special privileges of the nobility caused resentment from the other estates. Despite the introduction of new and more extensive taxes in the eighteenth century, such as the vingtième in 1749, the nobility seemed to get away with paying less than the rest of society. They were particularly adept at avoiding the most hated of taxes, the taille. The Third Estate. Everyone who did not belong to either of the first two estates was considered to be part of the Third Estate. Broadly speaking, the Third Estate was divided into the bourgeoisie (which consisted of merchants, financiers, doctors, writers, lawyers, civil servants) the peasantry and urban workers. The main concern of the bourgeoisie was to have more political representation while peasants, depending on their social standing in rural society, were simply worried about survival. The growing band of urban workers was increasingly vociferous about worsening living and working conditions. Of particular note were the artisan workers (or sans-culottes) who tended to be more educated and articulate than other workers. They became the more revolutionary and extreme members of urban society. Box 2: Translations of the text in the ribbons, banner and flag Ribbon in hand-‘Blast the scatterbrain who made me miss my turn’. Ribbon in hat-‘Oh well, everyone has a turn’. Banner-‘It is your fault. You should not have suggested the game’. Flag-‘Oh dear, for a long time now I’ve always lost with you’. Tasks 1 On the picture, number and label who you think is a) b) c) d) A (peasant?) worker A member of the nobility A clergyman A lawyer Explain your decisions in the following boxes. Indicate which estate each individual belonged to. The first box has been completed for you to give an example of how you should proceed Number and character 1 A lawyer (Third Estate) Explanation Number one seems to be a lawyer as he has a very learned, serious look on his face. He is wearing a long black gown and tall 20 black hat. This is rather formal looking attire suggesting the person in question is someone of authority. He is holding a banner which reads ‘It is your fault. You should not have suggested the game’. This kind of judgement is in line with what someone in the legal profession might have made at the time. However, it is not totally clear as to who he is blaming for starting the game although it is likely to be the clergyman. 2 A clergyman (First Estate) 3 A member of the nobility (Second Estate) 4 A sans-culottes (Third Estate) 2 The large drum is decorated with a royal coat of arms a) What does the drum represent? b) Why do you think the dice is being rolled on top of the drum? c) Who do you think has thrown the dice? What does this symbolise? Explain your answer. 3 Why do you think the artist has drawn a hand at the top of the pole holding up the banner? 4 Why do you think the artist has drawn a spade lying on the floor? 5 What message is being conveyed by the artist about the role of the Three Estates in the lead up to the French Revolution? Explain your answer. Further resources Access to other Waddesdon prints, online articles and other information about the French Revolution can be found here: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/french/research/revolutionaryprints/furtherresources/ Has this exercise changed the way you think about the Revolution? If so, tell us how and be in with a chance of winning a £20 Amazon voucher in our monthly draw by going to: 21 http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/french/research/revolutionaryprints/studentfeedback/ Suggested answers 1 Number and character 1 A lawyer (Third Estate) 2 A clergyman (First Estate) Explanation Number one seems to be a lawyer as he has a very learned, serious look on his face. He is wearing a long black gown and tall black hat. This is rather formal looking attire suggesting the person in question is someone of authority. He is holding a banner which reads ‘It is your fault. You should not have suggested the game’. This kind of judgement is in line with what someone in the legal profession might have made at the time. However, it is not totally clear as to who he is blaming for starting the game although it is likely to be the clergyman. The clergyman is the person sitting immediately behind the drum. He is wearing a hat and band (collar) characteristic of clergy apparel at the time. He looks rather demure and slightly taken aback. The comment attributed to him via his hat suggests that he believes the lawyer and/or noble are next in line to gamble their positions in society. It also suggests that maybe the clergy felt immune to any radical reforms that might be imposed as the Church was sympathetic towards the plight of the lower classes. 3 A member of the nobility (Second Estate) The noble sits on the chair to the left of the picture. He looks fearful possibly as he feels that he is about to lose all of his privileges, at the throw of a dice, to the Third Estate. The ribbon claims he has missed his turn at throwing the dice to gamble on his position. This may represent the idea that the nobility were reluctant to accept proposed reforms especially those that would end feudalism and give more political representation to the lower classes. 4 A sans-culottes (Third Estate) The artisan is shown standing to the right of the picture having just thrown the dice. He is working the traditional garb of the sans22 culottes; a waistcoat and breeches that fall just below the knees. The message on the flag that he is holding suggests that for some time the Third Estate has lost out to the other two Estates. It was now time for the Third Estate to gamble to improve their lot. 2 The drum probably represents the King (Louis XVI) and the Royal Court. The dice is probably being rolled on the drum to symbolise that the monarchy was under threat. Its future was dependent on the roll of a dice. The dice is being thrown by a sans-cullottes. This suggests that the instigation for change was from below (i.e. the Third Estate). It signifies that the Third Estate was about take away much of the political power held by the monarch and the other two Estates. 3 It is difficult to say for sure what the hand represents. It might signify a wish for proceedings to be halted or it might depict ‘the hand of fate’. 4 The spade is symbolic of the working classes who were part of the Third Estate. It reinforces the idea that the figure on the right is a sans-cullotes. 5 The main aim of the artist seems to be to convey the idea that the Third Estate are about to gain much authority and power from the other two Estates. The Third Estate was the group that had thrown the dice first and, it is implied, scored highly indicating that the time was ripe for radical change. However, the desire for a move towards a constitutional monarchy by the Third Estate is seen as a gamble. Success in the ‘game’ would be partly dependent on how the other players responded and how lucky they were. 23 The French Revolution and its short-term impact: an exercise in the interpretation of historical prints (2) Study the print below and complete the tasks listed underneath. Waddesdon Manor Accession number 4232.1.80.164 The print is a satirical etching produced in Paris, France in 1790. The printmaker was known as A.P. and was one of the most prolific producers of humorous prints during the period 1789-92. The print is quite busy and complex, depicting a number of events and issues that arose in the aftermath of the fall of the Bastille. To help you interpret the print and complete the tasks you will need to read: a) The background information in box 1 on some of the characters shown in the print. b) The translations in box 2 of the text shown at the top of and on the walls in the print. 24 Box 1: Background information on characters shown in the print Seven characters are depicted in the print. One is a soldier in uniform, wearing a bearskin hat and epaulettes. The coats of arms of France and Navarre appear on his hat. He carries a sword on his waist. He is undoubtedly a member of the National Guard. The Guard was formed on the 15th July 1789 shortly after the storming of the Bastille. The Guard was formed from the citizens’ militia on the instruction of the new governors of Paris, the Commune. The main aims of the Guard were to protect property against possible attacks from the menue peuple (ordinary urban dwellers) and to defend Paris against royalist forces. Thus, the Guard was essentially bourgeois in nature (sans-culottes were not allowed to be members of the Guard). However, the Guard belonged to the Third Estate and were, in the main, hostile towards the other two Estates (see exercise in interpretation of historical prints 1 for definitions of each estate). Another is a peasant who is clearly supportive of the actions of the soldier. There are two members of the Second Estate shown; both are wearing bicorn hats with feathers in but their predicaments are rather different. Four other members of the Second Estate are shown in the posters on the left hand wall. These posters depict the enemies of the Revolution who were associated with the Bastille, and were either executed or vilified by popular opinion. The characters are: -The Marquis de Launey, last governor of the Bastille; -the Baron de Besenval, who had deployed troops around Paris in July 1789; -the Marquis de Favras, who had plotted to abduct the king; -François Foulon, who was appointed in 1789 as Controller-General of Finances and minister of the King's household. He was unpopular in most circles as he seemed obsessed with accumulating personal wealth at the expense of the poor. There are also two members of the First Estate in the picture. The priests are both wearing the same dress (long tailed coats and bands) but, as with the aristocrats, their predicaments are different. Finally, there is a character that looks like an ape or monkey. Box 2: Translations of the text shown at the top of and on the walls in the print The title of the print translates as ‘With my crap they will never recover’. The sign on the left hand wall shows the ‘Street of Liberty’. The names on the four posters below the street sign are Besenval, Foulon, Favras, and de Launey (see Box 1). Below the lamp is a sign that says ‘The Aristocrat's Cul de Sac’ and above the archway a notice proclaiming ‘Hôtel de Broglie, for sale’. Above the double doors located on the 25 right is another sign which reads ‘String them up on the lampposts. Benevolent Louis the restorer’. Finally, the poster located above the right shoulder of the character on the right-hand side denotes ‘Ecclesiastical goods for sale: house in the market of Saint-Germain and Saint-Martin. Château located in Auteuil. Ask at the Abbey Saint-Genevieve’. Tasks 1 On the picture, number and label who you think is/are a) b) c) d) e) The soldier The peasant The two members of the Second Estate The two members of the Third Estate The ape looking character Explain your decisions in the following boxes. The first box has been completed for you to give an example of how you should proceed. Number and character 1 The soldier Explanation Number one is obviously the soldier as he is the only figure in military uniform and is carrying a sword. 2 3 4 5 2 Some commentators have suggested that this print refers to a number of events of 1789. These events are listed in the table below. What evidence is there in the print to indicate that it is depicting these events? By the side of each event list the evidence you can find. The first box has been completed for you to give an example of how you should proceed. You can also use your own knowledge to help you develop your comments. 26 Event Evidence from the print 1 The rising power of the After the formation of the National Constitutional Assembly and Third Estate the fall of the Bastille many of the Third Estate obtained voting rights and greater political representation. This new found power is depicted by the soldier defecating on an aristocrat (but, note, not on a clergyman). The authority of the Guard is emphasised not only by his position but also by his size; he is much bigger than the figures in the sewer below. 2 The storming of the Bastille 3 The renunciation of feudal privileges 4 The nationalisation of church property 5 Emigration 3 How and why is the peasant shown as being supportive of the action of the National Guard? 4 Why do you think the two characters in the centre and background of the picture are shown in an alleyway called the Aristocrat’s Cul de Sac? 5 Explain the significance of the lantern and sign on the building on the right hand side of the picture. 6 What is the overall message being conveyed by the artist about the impact of the early stages of the French Revolution? Explain your answer. Further resources Access to other Waddesdon prints, online articles and other information about the French Revolution can be found here: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/french/research/revolutionaryprints/furtherresources/ Has this exercise changed the way you think about the Revolution? If so, tell us how and be in with a chance of winning a £20 Amazon voucher by going to: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/french/research/revolutionaryprints/studentfeedback/ 27 Suggested answers 1 Number and character 1The soldier Explanation Number one is obviously the soldier as he is the only figure in military uniform and is carrying a sword. 2 The peasant The character standing on the right of the picture appears to be the peasant. He is shown wearing peasant type clothes; a waistcoat or jerkin, knee-length breeches, a plain shirt and clogs. A tricolour cockade decorates his hat. He is also represented alongside animals (a dog, a dead rabbit and dove or pigeon) thus reflecting a connection with the countryside. 3 The two members of the Second Estate The two members of the Second Estate (nobles) are shown in separate locations. One is shown in the open sewer alongside a member of the clergy. As it is unlikely that even a satirist would be so ungodly as to depict a member of the clergy being defecated on the person in the sewer suffering this indignity must be a noble. The other noble is shown in the alley way, sitting down and staring rather morosely at the Guard. The nobles can also be identified by the bicorn hats with feathers in that they are wearing. 4 The two members of the Third Estate The two members of the First Estate are located in the same place as those of the Second Estate. The clergy can be identified by their long coats and bands. The one shown in the alleyway appears to be engaged in a manual task, probably the grinding of cutlery or knives. This may be an attempt to indicate that the First Estate had fallen to the status of the Third Estate. The fact that the other clergyman is shown in the sewer being abused from above by the Guard reinforces this idea. 5 The ape looking character The character on the far left is the man with simian or ape-like features. He is staring from behind a wall marked with the street sign 'RUE DE LA LIBERTÉ'. He seems to be watching the soldier although it is not clear as to why he has his index finger held to his lips. He wears a cone-shaped hat with a cockade indicating that he is a representative of the revolutionaries. 2 Event Evidence form the print 1 The rising power of the After the formation of the National Constitutional Assembly and Third Estate. the fall of the Bastille many of the Third Estate obtained voting rights and greater political representation. This new found 28 power is depicted by the soldier defecating on an aristocrat (but, note, not on a clergyman). The authority of the Guard is emphasised not only by his position but also by his size; he is much bigger than the figures in the sewer below. 2 The storming of the Bastille This event is represented through the wall posters showing notables of Paris who were executed after the fall of the Bastille. There is further reference to the execution of opponents of the revolution in the form of decapitated heads (on the wall in the background) and the depiction of the lantern (see answer to task 5). 3 The renunciation of feudal privileges. The formal dismantling of the feudal system occurred from 4 to 11 August 1789. All forms of personal service were abolished without the demand that compensation should be paid by peasants. The popular symbol of this renunciation of feudal privileges (and hunting rights) was a dead dove or pigeon and a rabbit. These can be seen lying at the feet of the peasant. The general ‘freeing’ of members of the Third Estate is also emphasised by the role being played by the central character in the picture. 4 The nationalisation of church property. On the building above the peasant, a sign indicates a list of churches for sale, representing the nationalisation of church property. The inclusion of a Château highlights that many churchmen were also seigneurs (lords holding substantial property). 5 Emigration In the background, at the end of the cul-de-sac, there is another for sale sign placed on the Hôtel de Broglie. The Hôtel stands at 73, rue de Varenne (75007). The Duc de Broglie was supposedly 'a high-flying aristocrat, cool and capable of mischief'. He was called upon by Louis XVI to serve as the general of royal troops in the area around Paris. In July 1789 he ordered troops to march to the centre of Paris to quell potential disorder. This appeared to contribute to the decision to storm the Bastille. The artist links the de Broglie reference with a for sale sign to illustrate the Duc’s departure from Paris for Germany. Such an action would have been part of the more widespread emigration of aristocrats that was also occurring at this time. Within two months of the storming of the Bastille over 20,000 émigrés had fled abroad. 3 ‘How’-The peasant is showing his support for the actions of the soldier by laughing and clapping while looking in his direction. ‘Why’-Peasants had suffered badly as a result of the bad harvests of the 1780s, particularly that of 1788. They had played no part in the build-up to the revolution until the spring of 1788. Rising 29 bread prices and falling opportunities to make extra income from the production of textiles led to widespread discontent. After the fall of the Bastille there were rural demonstrations against taxes, the tithe and feudal dues. The Church and large owners were associated with grain hoarding. This was understandable as grain had been collected as part of the tithe and feudal dues. From as early as 20 July 1789 attacks on the chateaux of the very wealthy occurred and became part of what was called the Grande Peur (Great Fear). The peasant in the picture stands for all of the grievances peasants had by 1789. 4 The alleyway's street sign reads 'Cul de Sac des Aristocrate' which is a kind of pun (a word with more than one meaning); it suggests that both the aristocracy and clergy had found themselves at a political dead end. There was nowhere for them to go as they were now at the mercy of the Third Estate. 5 The term 'to the lantern or, to the gallows', suggests that this lantern may represent the lantern of the Place de Grève, where acts of popular justice were carried out just after the fall of the Bastille. Some who were deemed to be 'enemies of the people' were hanged. Louis XVI is shown looking over the scene in the form of a bust. The text, 'Benevolent Louis the restorer' shows that the general population still thought of the King as someone who could rule in a kindly way and restore stability to France. This text provides the image with another pun naming Louis not only as a restorer of liberty, but perhaps as a restaurateur as well i.e. one who runs a restaurant. This could also reference establishments that served 'restorative' bouillons (a healthy soup). In other words there was a possibility that law and order would soon be restored under an ‘enlightened’ king. 6 The overall message is that after the fall of the Bastille the Third Estate was in a strong position. They had taken away a large amount of authority of the other two Estates. Reforms had occurred which had completely changed the nature of French society. However, there is indication that the artist believed that the story was not over. Louis XVI is depicted as still having a degree of popular support and the way the clergyman and noble are depicted in the alleyway suggests that there was a possibility of a counterrevolution. This is reinforced by the reference to emigration, the implication being that although the nobility had fled there was a possibility they would return at a later date to take revenge. 30