NATIONAL TREASURY PPP MANUAL NATIONAL TREASURY PPP PRACTICE NOTE NUMBER 05 OF 2004

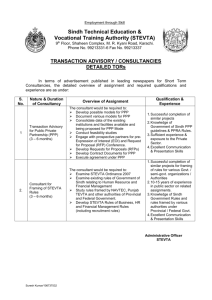

advertisement