Topographical Bibliography Forming Material Egypt Origin of the project Vincent Razanajao

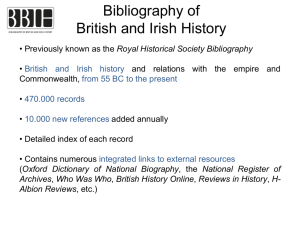

advertisement

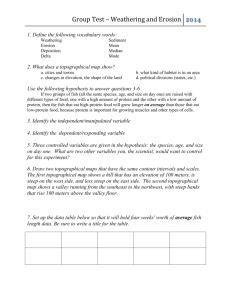

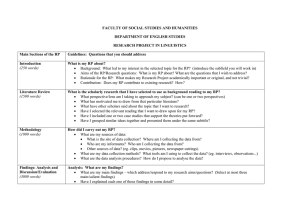

The new developments of the Topographical Bibliography: Digital Humanities to serve Forming Material Egypt Vincent Razanajao Editor of the Topographical Bibliography& Keeper of the Griffith Institute’s Archive, University of Oxford Origin of the project The Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintingsis a bibliographical tool well known by the community of Egyptologists. Built around an idea conceived in the late 19th century – mainly by Fr. Ll. Griffith –, and materialized by the efforts of Bertha Porter and Rosalind Moss in the 1920s (hence, the work is often referred to as Porter&Moss), this research project brings together, analyses, and synthesizes printed and archival material, providing comprehensive published and unpublished information about ancient Egyptian inscribed artefacts and monuments. Organized according to the location or provenance of the monumentsbeing described, the bibliographic information should in theory only be relating to inscribed material. Nevertheless, the necessity to connect texts to a context implies that,alongside bibliographic data, this information also includes descriptions of archaeological sites and monuments, details of the iconography, and summaries of the content of the texts. The first volume of the Topographical Bibliography, dealing with the Theban Necropolis, was published in 1927, followed two years later by a second volume on the Theban temples. During the twenty following years, seven volumes werepublished, leading the Topographical Bibliography to cover all the Nile Valley and the Delta, as well as ancient Nubia, the deserts, and parts of the Ancient World where Egyptian monuments were found.As such, the Topographical Bibliographyis recognised as a universally and essential point of departure for research and a very good means for scholars to get a precise view on archaeological sites, someof which still await proper publication. After the publication of the seventh volume of the Topographical Bibliography in 1951, the need of a revised edition clearly arose, and less than ten years later the second and revised edition of the first volume was published. Since then, only three of the seven first volumes of the Topographical Bibliography have been the subject of a revision, mainly because of the endless increase of bibliographical data, butalso because the work has had to be focused on the eighth volume which deals with a substantial material, namely the objects of provenance not known. 1 Towards the digital transformation of the Topographical Bibliography The future development of this indispensable tool – perhaps less indispensable than in the past because of the lack of published updates – implies to move to an electronic provision and an online presentation. This digital transformation is a necessity for obvious practical reasons – how to face a huge amount of data –, but also because digital humanities offer new features that will enhance and strengthen the research tool itself. Digitization of the existing material Taking into account thatthe amount of new publications never ceases to increase, a complete shift in the way the data is recorded and published has appeared to be a necessity. The traditional practice of printed text cannot be used anymore and electronic publishing has become indispensable. A first task will be to digitize the existing printed volumes, i.e. around 5500 pages of “plain” text. Beyond the proper scan and optical recognition of the text, this digitization will consist in marking up the text with XML tags, mainly on bibliographical references, place and personal names (both ancient and modern), archaeological terms, etc. To this core material stemmed from the printed volumes will be added the new analyses and updates that have never ceased to be gathered at the Griffith Institute. This is one of the major issues to be tackled, since these new analyses and corrections are basically written down by hand onto small pieces of paper, the so-called Appendix-slips. At first sight, these slips will not be digitized because of their nature (hand-written, erasures, insertions…) and quantity (around 100.000 slips?), but their contents must be taken into account. Another obvious practical reason to shift to digital provision and presentation is the existence of the Online Egyptological Bibliography, a project now hosted at the University of Oxford that will serve as a bibliographical repository. Electronic provision and online presentation The digital transformation will go far further than a simple formal change, the goal being not to simply put into a digital form what was previously printed as books. The digital transformation of the Topographical Bibliography will be, first and foremost, the opportunity to develop new conceptual approaches. Indeed, by the nature of the Topographical Bibliography itself, which was conceived by its creators according to a quite strict plan, a XML marking up of the text will lead to the forming of a highly structured material, through which it will be possible to go step by step in the details of a site or a monument. It should thus be possible to practically visit an area or an archaeological site, a tomb or a temple, by following the hierarchical structure of the site until 2 the desired level of detail (e.g.Lower Egypt > Eastern Part > Tell Faraʿun > Sacred Area > Main Temple > Block-Statue of royal scribe Merenptah). It is easy to imagine that this navigation will be performed through tree-structured menus, which will expand according to the user’s choices, but the implementation of graph technologiesto browse the material will also be investigated. This digital form of the material should also make easier the connexion between facts of different natures, such as archaeological evidences or monuments, and more abstract elements,like mentions of ancient placenames or names of institutions. For an ancient town, for instance, it should thus be possible to get a listing of all the monuments known from archaeological sources as well as those known (sometime only) from textual sources. To the textual and tree-structure approach, a proper geographical and topographical onewill be implemented by using a Geographical Information System (GIS). This approach will first aim at anchoring the bibliographical data into the physical space itself, thus offering an easy way to explore the material through maps and plans, includingalso the possibility to focus on a particular period of time.Such an approach should also be able to take into account archival documentation and ancient excavation records, which are occasionallyvery difficult to accurately place on a map, but whose information is invaluable. Digital technologies will then offer to apprehend differently the contents of the Topographical Bibliography – or, in others words, of ancient Egypt itself –, by enabling to query the data in both its geographical and historical dimensions, giving the opportunity to get a complete picture of a town at a certain point in time in a very easy way. The Topographical Bibliography and open data The Topographical Bibliography must also take into account the digital projects and databases developed by otherEgyptological institutes.The two main categories of databases to deal with will be, on the one hand,the catalogues of objects held by museums and, on the other,the documentary databases that focus on a site or on a particular categorie of material or objects. Several projects launched during these last decades often overlap to a certain extent the scope of the Porter & Moss(Giza Project; Karnak Project; KarnakCachette; Meketre; Trismegistos…).Rather to compete with these projects – how a single team could do the task of several ones –, it seems conceivable and essential to work in synergy by implementing linked and open datamethodology.If this implies to develop or(re)define Egyptological standards in order to enable communication between Egyptological projects, the Topographical Bibliography will mainly work at developing a framework through which data exchange will be made possiblewithout imposing– and this is very important–any constraints to other projectsin terms of database or research questions,for instance. Web 3 semantics technologies and standards such as CIDOC-CRMwill be at the core of this process, and projects such as Claros or ResaerchSpace will constitute the model to follow. Conclusion By giving a digital rebirth to the Topographical Bibliography, the Griffith Institute certainly aims at perpetuating this almost hundred-year-old project and making accessible the data that has never ceased to be analysed and gathered, but it also aspires to renew its approach and position within Egyptology. By becoming also like a central point where data from other Egyptological projects could meet, facilitating interoperability between vast sets of data, the Topographical Bibliography could thencontinueto contribute to the major issues raised by the dispersal of Ancient Egyptian heritage. Online projects mentioned Griffith Institute - http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/ OEB - http://oeb.griffith.ox.ac.uk/ ResearchSpace - http://www.researchspace.org/ CLAROS - http://www.clarosnet.org CIDOC-Conceptual Reference Model (CRM) - http://cidoc-crm.org/ Giza Archive Project - www.gizapyramids.org/ GIS-Centre, Supreme Council of Antiquities, Egypt - http://www.giscenter.gov.eg/ Karnak Cachette - http://www.ifao.egnet.net/bases/cachette/ Karnak Project - http://www.cfeetk.cnrs.fr/index.php?page=projet-karnak Meketre Project - meketre.org/ Trismegistos - http://www.trismegistos.org/ 4