COURSE HANDBOOK & SYLLABUS Caribbean Archaeology (Arcl.3049) 2011-2012

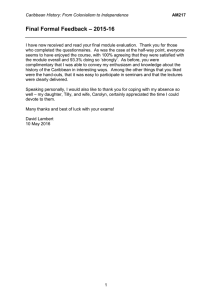

advertisement