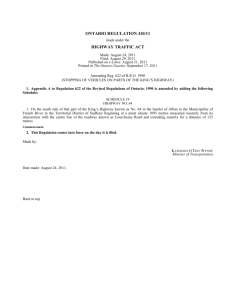

Legal Research Digest 51 NATIONAL COOperATIve hIghwAy reseArCh prOgrAm

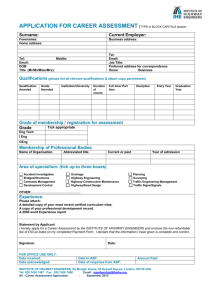

advertisement