Cohabitation, marriage, relationship stability and child outcomes: final report

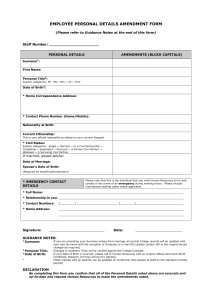

advertisement