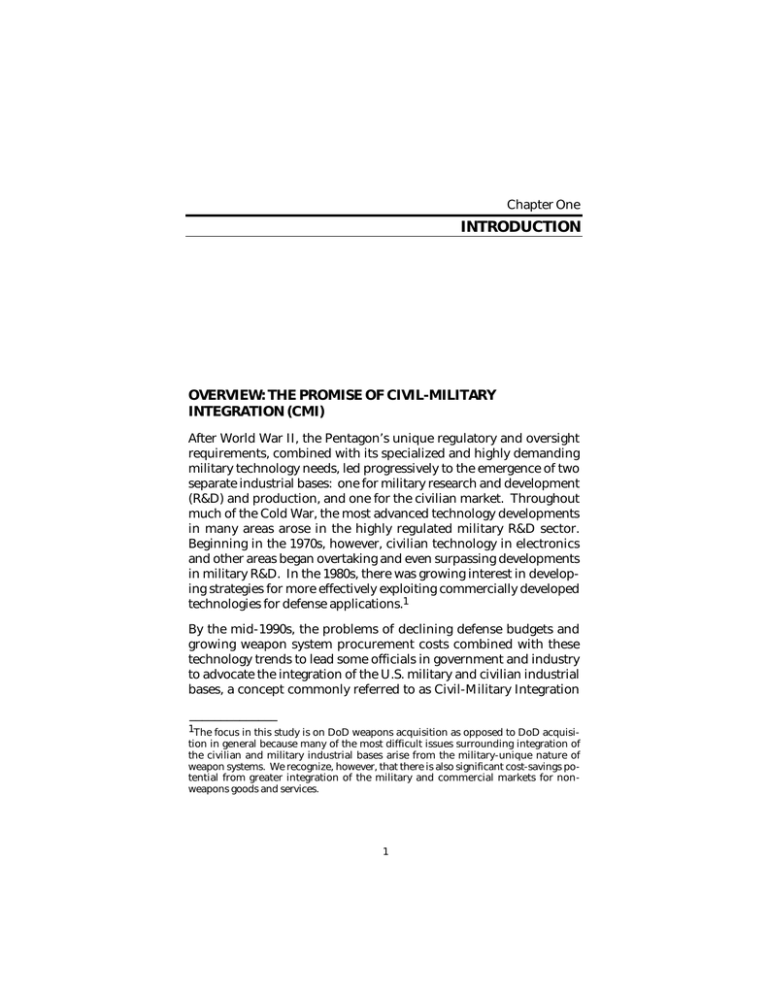

INTRODUCTION OVERVIEW: THE PROMISE OF CIVIL-MILITARY INTEGRATION (CMI)

advertisement

Chapter One INTRODUCTION OVERVIEW: THE PROMISE OF CIVIL-MILITARY INTEGRATION (CMI) After World War II, the Pentagon’s unique regulatory and oversight requirements, combined with its specialized and highly demanding military technology needs, led progressively to the emergence of two separate industrial bases: one for military research and development (R&D) and production, and one for the civilian market. Throughout much of the Cold War, the most advanced technology developments in many areas arose in the highly regulated military R&D sector. Beginning in the 1970s, however, civilian technology in electronics and other areas began overtaking and even surpassing developments in military R&D. In the 1980s, there was growing interest in developing strategies for more effectively exploiting commercially developed technologies for defense applications.1 By the mid-1990s, the problems of declining defense budgets and growing weapon system procurement costs combined with these technology trends to lead some officials in government and industry to advocate the integration of the U.S. military and civilian industrial bases, a concept commonly referred to as Civil-Military Integration ______________ 1The focus in this study is on DoD weapons acquisition as opposed to DoD acquisition in general because many of the most difficult issues surrounding integration of the civilian and military industrial bases arise from the military-unique nature of weapon systems. We recognize, however, that there is also significant cost-savings potential from greater integration of the military and commercial markets for nonweapons goods and services. 1 2 Cheaper, Faster, Better? Commercial Approaches to Weapons Acquisition (CMI). 2 According to advocates, Department of Defense (DoD) adoption of CMI would • Reduce costs of acquiring and supporting weapon systems • Improve performance at Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and throughout the life cycle of a weapon system • Shorten development times • Improve reliability and maintainability • Help maintain the defense-relevant portion of the industrial base.3 Some advocates have argued that the cost savings to DoD from CMI could be as high as $45 billion annually.4 The advocates of CMI base their arguments on two sorts of assumptions about the nature of the commercial versus military worlds. First, they assume there is an extensive “dual-use” overlap between commercial and military process and product technologies. According to advocates, many technologies, manufacturing processes, parts, components, and so forth are directly applicable to both commercial and military products, so that labor, research, production facilities, and other types of plant and equipment can be treated as dual-use. Second, they believe that DoD adoption of commercial business practices, in the context of the incentives and constraints provided by a more commercial-like market structure, will spur the development of high-performance weapon systems at lower costs than can be achieved under the current heavily regulated military acquisition process. Many advocates argue that, by adopting ______________ 2Although the term “CMI” takes on a variety of meanings in the literature, one commonly used definition is “the process of uniting the defense and commercial industrial bases so that common technologies, labor, equipment, material, and/or facilities can be used to meet both defense and commercial needs” (OTA, 1994, p. 42). We broaden this definition slightly to include DoD adoption of commercial market practices. 3The rationale for CMI and its expected benefits are discussed in several DoD documents, including Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology (OUSD/A&T) (1995, 1996). 4See, for example, Gansler (1995). Introduction 3 commercial-like business practices, DoD can benefit from CMI even if militarily relevant products and technologies are not fully dual-use. In basic agreement with the arguments of the CMI advocates, DoD leaders have begun to relax the web of regulatory restrictions that segregate weapon system acquisition from common commercial market practice and impose a cost premium on items purchased by the government. DoD leaders now insist that both the incentives and the constraints that prevail in military markets must be altered so that DoD and its defense contractors can begin to behave more like “normal” commercial buyers and sellers. This could require more extensive reform of the regulatory environment—and, in particular, reform of the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) and Defense Federal Acquisition Regulations Supplement (DFARS)— than has already been achieved through ongoing DoD efforts. But probably more important, advocates say, to achieve the full benefits of CMI will require full and effective implementation of existing reforms by the military services. Critics respond that even extensive acquisition reform will not result in the benefits promised by advocates of CMI. They argue that in fact there is little dual-use overlap between civilian and military products and processes in many crucial technology areas, so that integration of the defense and commercial industrial bases is simply not possible. They also believe that without regulatory safeguards, competitive incentives and constraints will be inadequate to ensure DoD access to high-performance weapon systems at a reasonable price. Given this market failure, they argue, a specialized cadre of defenseoriented firms operating under close governmental supervision is the best solution to U.S. national security needs. Further, even those who believe in the basic promise of CMI have concerns about the effectiveness of its implementation by DoD. One worry is that Pentagon acquisition personnel may not receive adequate training and support to make the often-difficult decisions required of them in a commercial-like environment. For example, DoD managers may find it difficult to separate “must-have” system requirements from those that are only “nice-to-have,” so that appropriate cost/performance tradeoffs are not made. DoD managers may also be reluctant to surrender control over weapon system configuration to contractors, but their failure to do so would reduce contrac- 4 Cheaper, Faster, Better? Commercial Approaches to Weapons Acquisition tors’ ability to make the changes necessary to provide many of the benefits promised by CMI. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES This monograph report explores the issues surrounding the more effective utilization of the civilian industrial base by DoD and the U.S. Air Force. We focus on two issues: the dual-use applicability of certain commercial technologies, and the risks and benefits to DoD of moving from a regulation-based approach to acquisition to a more commercial-like approach in which DoD emulates the practices developed by commercial customers. A brief history of how the U.S. civilian and defense industrial bases came to be separated is presented in Chapter Two, which also lays out the principal arguments and evidence for and against CMI. In Chapters Three through Five, we discuss to what extent CMI might be appropriate to radio frequency (RF) microwave devices, a traditionally defense-specific technology that is of critical importance to future Air Force combat aircraft capabilities. Specifically, we seek to answer the following questions: • Is the commercial market in military-relevant electronics large enough to encompass an adequate range of technologies, parts, and components required to support a comprehensive CMI strategy for military-specific microwave subsystems such as firecontrol radars? (Chapter Three) • Is the civilian market driving technology at a rate and in a direction that meets national security requirements? In other words, can CMI provide the necessary and desired performance capabilities? (Chapter Four) • Are there cost and schedule benefits from inserting commercially derived parts and technology into military systems such as RF/microwave systems? (Chapter Five) In Chapters Six and Seven, our research objective is first to identify business practices and strategies used in the commercial aircraft industry that could lead to a more cost-effective structuring of Air Force weapon system programs, and second to examine and assess experimental and pilot programs initiated by the Air Force, the Introduction 5 Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), and the other services that contain key elements of the commercial approach. The questions are: • What mechanisms have commercial market participants evolved to reduce risks associated with the development, production, and maintenance of transport aircraft? To what extent are they relevant to DoD? (Chapter Six) • To what extent, and with what success, have commercial-like approaches been applied to military programs, and what can be learned from them for future efforts? (Chapter Seven) Our conclusions are summarized in Chapter Eight. THE DUAL-USE APPLICABILITY OF COMMERCIAL TECHNOLOGIES We begin by identifying candidate technology areas and a set of case studies to examine the dual-use applicability of commercial technologies. For this study, we select avionics because of its growing importance and cost for combat aircraft, and because the size and vitality of the nonmilitary electronics market should provide ample opportunities for CMI. To make the problem more manageable, we narrow our focus to defense-specific RF/microwave devices in the following two applications: • Fighter fire-control radars • Fighter electronic warfare (EW) systems. Within these categories, we pay particular attention to the problem of developing cost-effective electronically scanned phased-array antennas. Here the key technological areas of interest are the transmit/receive (T/R) modules that populate the antenna array and that employ advanced gallium arsenide (GaAs) monolithic microwave integrated circuit (MMIC) chips.5 Finally, we also examine some of the less exotic digital and RF devices used in fighter Communication, ______________ 5For an overview of the enabling technologies, see McQuiddy et al. (1991). 6 Cheaper, Faster, Better? Commercial Approaches to Weapons Acquisition Navigation, and Identification (CNI) systems. 6 We chose these technological areas for three reasons: (1) the continuing growth of cost in fighter avionics; (2) indications that RF/microwave technology is opening up to increasing commercialization, thus offering CMI opportunities that did not exist in the past; and (3) high-level Defense Department advocacy of greater CMI in the field of military radars.7 We conducted case studies of programs involving a variety of military-specific RF/microwave technologies that, when taken together, represent many of the key dual-use elements of CMI. Some of them are pilot programs or innovative R&D efforts funded by the government and aimed at incorporating key aspects of CMI and other acquisition reform measures. Others are contractor-funded attempts to develop new low-cost systems based on commercial technologies. Some of the programs have produced only paper studies, but most involve the development of test hardware. The following nine programs involve technologies directly applicable to RF/microwave, including fire-control radars and electronic warfare systems: — Multifunction Integrated Radio Frequency System (MIRFS) Program — Radar System Aperture Technology Program (RSAT) — Advanced Low Cost Aperture Radar Program (ALCAR) — Low Cost Radar Program (LCR) — Modular Radar Program (MODAR) — Modular Radars (AN/TPS-74) ______________ 6For the importance of microwave technology in a broad spectrum of defense applications, see Bierman (1991). 7For example, Dr. Paul Kaminski, former Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology, stressed the significance of three key elements of a strategy for affordable radar systems: effective concepts of operations, compatible system architectures, and “the need to pursue acquisition approaches that leverage the broadest possible commercial industrial base.” In a discussion on the future of radar technology in 1996, Dr. Kaminski pointed out that “one of the principal objectives of our acquisition reform program is to open the defense market to commercial companies and technology—not only the primes, but subtier suppliers as well.” Quotations from Kaminski (1996). Introduction 7 — AN/ALQ-135 upgrade/support — AN/ALQ-99 upgrade/support — Technology Reinvestment Program (TRP): RF/Microwave/ Millimeter-wave (MMW) technologies.8 The first four are related to the development of new technology, lower-cost electronically scanned array (ESA) radar systems or antennas, and the next two involve development of low-cost conventional military radars. The two AN/ALQ case studies involve support and upgrade of existing EW systems. The last program is a government-sponsored effort aimed at developing microwave and millimeter-wave devices with both defense and commercial applications. In CNI technologies, we examined the following four programs: — Manufacturing Technology Industrial Base Pilot Program (Mantech IBP): Military Products from Commercial Lines — Integrated Modular Avionics: F-16 — Integrated Modular Avionics from Commercial Lines: F-22 — Programmable Digital Radio (PDR). The first three are related innovative fighter programs, and the fourth is a commercially developed component of a CNI system. We chose these programs for our case studies because they are all characterized by one or more of the following attributes: • Significant use of commercially derived designs or technologies during R&D • Insertion of commercial components and parts • Employment of dual-use production facilities or manufacturing technologies (mantech) ______________ 8The official program title is “Development and Application of Advanced Dual-Use Microwave Technologies for Wireless Communications and Sensors for IVHS Vehicles,” but the scope of the effort has been broadened considerably since this title was formulated. 8 Cheaper, Faster, Better? Commercial Approaches to Weapons Acquisition • “Spin-off” of military technologies to commercial applications with an eye to future “spin-back” of commercial technologies to defense applications. We acquired most of the information and data on these programs through interviews with government program managers and other government officials, and with industry officials. Companies whose representatives were interviewed included: • Raytheon Sensors and Electronic Systems, El Segundo, California9 • Northrop Grumman Electronic Sensors and Systems Sector, Baltimore, Maryland 10 • TRW Space and Electronics Group (ASG), San Diego, California • Northrop Grumman Electronic Systems, Rolling Meadows, Illinois • M/A-COM, Lowell, Massachusetts • AIL Systems, Inc., Deer Park, New York • Raytheon Corporation, Washington, D.C. • Northrop Grumman Xetron, Cincinnati, Ohio. We also consulted a wide array of published materials and other sources. Of particular interest were materials provided either directly or indirectly by the following organizations: • Avionics Directorate, Wright Laboratory, Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC), Wright Patterson Air Force Base • Manufacturing Technology Directorate, Wright Laboratory, AFMC, Wright Patterson Air Force Base • Electronic Systems Center, Hanscom Air Force Base ______________ 9In January 1997 Raytheon acquired the military components of Hughes and absorbed them into the Sensors and Electronic Systems Division of the Raytheon Systems Company. 10 Formerly the primary military products division of Westinghouse Electric Corporation. Introduction • Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) • Electronics Industry Association (EIA) • Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA). 9 A COMMERCIAL-LIKE APPROACH TO ACQUISITION The second part of the report broadens the scope of our investigation to consider how DoD might benefit from relying on relevant commercial business practices rather than regulation to obtain lowcost, high-performance weapons systems—whether or not products and technologies are fully dual-use. The first of our two case studies summarizes the experience of a relevant commercial market; the second looks at DoD’s own initial experience in a variety of ongoing pilot programs aimed at testing a commercial-like approach to acquisition. For the first case study, we began by identifying commercial markets that share important structural features in common with the market for weapon systems. Using as selection criteria characteristics such as high technology content, large fixed costs of R&D and production, high performance and reliability requirements, and relatively small numbers of buyers and sellers, we chose to examine the commercial transport aircraft industry. We analyzed the arrangements that commercial airlines, airframe integrators, and aircraft equipment and parts suppliers have set up since the 1979 deregulation of the airline industry to control costs and ensure good performance over the lifecycle of an aircraft. We examined • “Must cost” pricing structures and their implications for cost/performance tradeoffs • Closer buyer-supplier relationships, including sharing of R&D, testing, and certification costs • Buyer strategies such as cooperative acquisition, open industry standards, and “best value” sourcing • Contractor configuration control and continuous technology insertion over the life-cycle of systems and subsystems. 10 Cheaper, Faster, Better? Commercial Approaches to Weapons Acquisition Many of these arrangements are highly relevant to DoD acquisition of military aerospace systems. We next identified existing military acquisition reform initiatives and pilot programs that attempt to approximate a commercial acquisition environment, and assessed these programs on the basis of design and implementation. Although all of the DoD acquisition pilot programs are limited in their application of commercial practices, they offer lessons to those considering a more widespread adoption of CMI. To capture these lessons most fully, three types of programs were considered: • Service munitions programs that from their inception focus on developing military-unique combat systems under the direction of the user services • DARPA acquisition technology demonstration programs that operate outside the normal acquisition environment • Service modification and upgrade programs. Our primary sources of data and information for both the commercial aircraft industry and DoD pilot program case studies were industry interviews and public materials available either in hardcopy or over the web. Companies whose representatives were interviewed included: • Boeing Commercial Aircraft Group, Seattle, Washington • Lockheed Martin Skunk Works, Palmdale, California • Boeing McDonnell Aircraft and Missile Systems, St. Louis, Missouri11 • Boeing Douglas Products Division, Long Beach, California • Northrop Grumman Integrated Systems and Aerostructures Sector, Dallas, Texas ______________ 11 McDonnell Douglas was acquired by The Boeing Company in August 1997. Although some interviews were conducted after the acquisition, for simplicity we use the former McDonnell Douglas name. Introduction 11 • Northrop Grumman Integrated Systems and Aerostructures Sector, Hawthorne, California • Raytheon Beech Aircraft Company, Wichita, Kansas • Raytheon Sensors and Electronic Systems, El Segundo, California • Teledyne Controls, Los Angeles, California. 12 Only nonproprietary or generic information is presented throughout the report to permit wide distribution of our findings. ______________ 12Teledyne Controls is a fully owned subsidiary of Allegheny Teledyne Inc.