Reproduction Kill or Cure:

advertisement

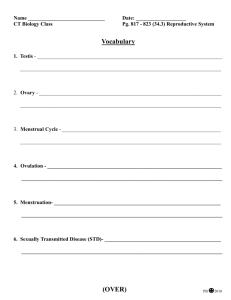

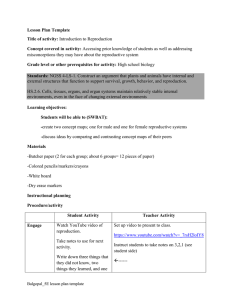

Kill or Cure: Reproduction Aims • To introduce the theme of reproduction and reproductive health • To think about reproduction as both a scientific and social issue, at once public and private. • To think about reproduction as ‘natural’ yet also ‘medicalised’ and ‘technologised’ • To explore three aspects of reproductive health: maternity; fertility control; and assisted reproduction. Part one • Reproductive health Introduction to reproductive health • Reproductive health is defined as a state of physical, mental, and social well-being in all matters relating to the reproductive system, at all stages of life. • Good reproductive health implies that people are able to have a satisfying and safe sex life, the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when, and how often to do so. • Men and women should be informed about and have access to safe, effective, affordable, and acceptable methods of family planning of their choice. • Women should have the right to appropriate healthcare services that enable women to safely go through pregnancy and childbirth. Part two • Maternity Maternal mortality • Obstetrics had developed significantly by the early 20th century. Despite these changes the majority of births were still at home, attended by midwives. • As the century progressed the medical involvement in birth grew. • However giving birth continued to carry risks - and generate very real fears - for women. • While from the end of the nineteenth century there was a steady decline in mortality in general, in infant mortality, and in mortality from infectious diseases, maternal mortality was the great exception. Mortality rates Infant mortality per thousand births 1900-1990 Annual death rate per 1000 total births from maternal mortality in England and Wales (18501970) The medicalization of birth • In the 20th century childbirth in the developed world moved from the home to the hospital. • Associated with this new birthing space were childbirth technologies. Hospitals provided a hi-tech, highly medicalised birthing experience. • Obstetricians began defining ‘normal’ standards for childbirth. The epitome was Friedman’s curve, developed by Emanuel Friedman, a graphic representation of a ‘normal’ labour. Deviations from normality were seen as reasons for medical intervention. Part three • Fertility control Reasons for the fertility decline I 1. As the infant death rate declined, more babies survived into adulthood, thus fewer pregnancies produced surviving offspring. So it was not necessary for parents to have more children than they expected to survive into adulthood. 2. As methods of efficient birth control improved, access to contraception became easier and knowledge of them spread. 3. There was a greater willingness to use contraceptives. 4. Men’s attitudes towards women softened so that they have been more willing to use contraceptives in order to help relieve women of the health risks of frequent and closely spaced pregnancies, and the hard work associated with a large family. 5. Simon Szreter argues that abstinence was the English way of adjusting fertility in response to the perceived relative costs of having children. The perception of the escalating ‘costs’ of childrearing provided the conscious motivation to control births. The anti-sexual culture was conducive to the use of abstinence as the method to achieve that goal, and provided married men and women with a legitimating, anti-sexual rationale. Reasons for the fertility decline 2 6. In Britain, Joseph Banks has argued that the economic depression of the 1870s and 1880s undermined middle-class confidence in the future and encouraged the use of birth control to maintain living standards. 7. In America, Daniel Scott-Smith has argued that the decline in middleclass fertility offers an indication of ‘domestic feminism’ (the power and autonomy exercised by women within the family). Population control movement Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) • In the 20th century, population control proponents drew from the insights of the British clergyman Thomas Malthus, who published An Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798. • He outlined the idea of ‘positive checks’ and ‘preventative checks’ to control the population. • ‘Positive checks,’ such as diseases, war, disaster and famine, are factors that Malthus considered to increase the death rate. • ‘Preventative checks’ were factors that Malthus believed to affect the birth rate, such as moral restraint, abstinence and birth control. Eugenics • Eugenics, meaning ‘well born,’ was introduced in the 1880s by Sir Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin and the father of modern statistics. • Galton pioneered the use of pedigrees, twin studies, and statistical correlation for the purpose of using that knowledge to improve ‘the breed of man.’ • During the early 1900s, eugenics became a serious scientific study pursued by both biologists and social scientists. Pro-natalism • The Boer War 1899-1902 revealed a shockingly low standard of health among the male population recruited to fight, forcing political attention on the actual condition of the Empire’s citizens. • Infant welfare was included in the campaign to improve physical efficiency, and this concern became, according to Jane Lewis, even more explicit during WWI. It would only further increase by WWII. • By 1939 the British birthrate had dropped to below replacement levels, even lower than in 1914, and hit an all-time low in 1941. In response a pronatalist position, whereby women were encouraged to have more children, was widely adopted by the government and others, including labour organisations and members of the medical profession. Contraceptive pill • Developed by American biologist Dr Gregory Pincus, the ‘Pill’ works by suppressing ovulation. • It was tested in the 1950s on Puerto Rican and Haitian women and launched in the USA in 1960. • In the USA, around 1.2 million women used the Pill within two years of its launch. A decade later the numbers had risen to ten million • Worldwide, around 100 million women take the Pill. • Scientific debate about the health risks of oral contraceptives continues. Pharmaceuticals and foreign aid • The dictates of the market play a major part in family planning and population control. • About $5 billion is spent each year on family planning by developing countries; $1 billion of this is donated by Northern governments, multilateral agencies and private organizations. • Pharmaceutical companies have global contraceptive sales of $2.6 billion to $2.9 billion per year. • This huge economic power of pharmaceuticals enables them to influence the policies of Southern governments and the priorities of the medical establishment. • According to the UN, contraceptive use in the southern hemisphere has increased five-fold in the past quarter century because of the intervention of foreign-aid donors and international institutions. International Conference on Population and Development (1994) The ICDP brought to international recognition two important guiding principles of reproductive and sexual health: 1) that empowering women and improving their status are important ends in themselves and essential for achieving sustainable development; 2) that reproductive rights are inextricable from basic human rights, rather than something belonging to the realm of family planning. Move to reproductive health • Three developments were of particular importance to the reappraisal of reproductive health in the 1990s: • Firstly, the growing strength of the women’s movement and their criticism of the over-emphasis on the control of female fertility - and by extension, their sexuality - to the exclusion of their other needs. • Secondly, the advent of the HIV/AIDS pandemic; suddenly it became imperative to respond to the consequences of sexual activity other than pregnancy, in particular sexually transmitted diseases. But perhaps more important, it became possible (and essential) to talk about sex, about sexual relations outside of marriage as well as within it, and about the sexuality of young people. • Thirdly, the articulation of the concept of reproductive rights. An interpretation of international human rights treaties in terms of women’s health in general, and reproductive health in particular, gradually gained acceptance during the 1990s. Part four • Assisted reproduction Artificial insemination • Artificial insemination in humans was first performed by the famous English surgeon John Hunter, in 1785. • In 1884 the first successful artificial insemination of a married woman by donor sperm occurred in the United States. John Hunter (1728-1793) IVF and Louise Brown Criticisms and concerns • Ann Oakley has noted how infertility treatments are often unpleasant and their success rates remain relatively low. • Gillian Tindall has demonstrated how babies created through assisted reproduction are at excess risk at every stage in their development. • In the British context, the issue of cost to the NHS has also been an issue. • In the development of ever more powerful techniques of assisted reproduction a number of new ethical questions have emerged. They lie at the heart of what it means to reproduce, to be a parent, to be a human being. • Since 1990 many countries have been setting out to establish ethical guidelines and laws for reproductive technologies. Warnock Report • In 1982 a committee was established to inquire into the technologies of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and embryology. • This was in response both to concern at the speed with which these technologies were developing and to the 1978 birth of Louise Brown. • The committee was chaired by the philosopher Mary Warnock. It concluded that the human embryo should be protected, but that research on embryos and IVF would be permissible, given appropriate safeguards. • The committee proposed the establishment of a regulatory authority with the remit of licensing the use in treatment, storage and research of human embryos outside the body. This body would later become the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. • The findings of the committee were published in what is now referred to as the Warnock Report in 1984, and forms the basis for the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act. Conclusions • Reproduction and the family are central elements in the lives of people. • In the 20th C obstetricians began defining ‘normal’ standards for childbirth. • There was a move away from ideas of population control and demographic targets towards a more holistic approach to reproductive health. • With new reproductive technologies new ethical questions have emerged. • Perceptions about reproduction have shaped medical practices, public policy, legal rights, technology, and the contours of everyday experiences.