Document 12787112

advertisement

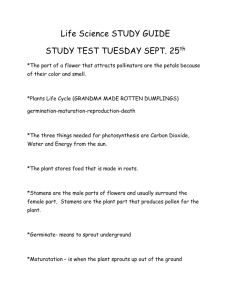

Made in United States of America Reprinted frmn THE JouRNAL OF ';\'ILDLIFE 1L\.NAGEMENT Vol. 32, No. 1, January 1967 pp. 104-108 SNOWSHOE HARE PREFERENCE FOR SPOTTED CATSEAR FLOWERS IN WESTERN WASHINGTON BY :tvl. A. RAnwAN AND D. L. CAMPBELL PuRCHASED llY TilE FOREST SERVICE, U, S, DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, FOR OFFICIAL USE, SNOWSHOE HARE PREFERENCE FOR SPOTTED CATSEAR FLOWERS IN WESTERN WASHINGTON M. A. RADWAN, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, D. L. CAMPBELL, U. U. S. Forest Service, Olympia, Washington S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Olympia, Washington Abstract: Relative preference by snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus washingtonii) for leaves, flower buds, and open flowers of spotted catsear ( H ypochoeris radicata) was studied in western Washington. The hares demonstrated preference for open flowers, followed closely by flower buds. Leaves, alone or in presence of open flowers or flower buds, were the least preferred part of the plant. Sugar content was calculated on both fresh- and dry-weight bases, and advantages of the former method are dis­ cussed. Based on fresh weights, levels of glucose and fructose-the principal sugars of catsear-ap­ peared to be responsible for the observed order of preference, although other factors were not ruled out. The snowshoe hare causes significant damage to seedlings of Douglas fir (Pseu­ dotsuga menziesii) in the Pacific North­ west (Moore 1940:18, Munger 1943:55 ) . At present, the most common control method against the hare uses repellent formulations. However, even the best repellent now avail­ able protects seedlings no longer than through winter dormancy following treat­ ment (Besser and Welch 1959:168 ) . Better, longer lasting repellents or perhaps new control measures are needed. Development of better control methods requires a thorough knowledge of the snowshoe hare, especially its habitat re­ quirements. During home range determina­ tion studies with radio-instrumented hares in western Washington, the junior author found spotted catsear to be one of this ani­ mal's preferred foods. Hares utilized the plant all year but fed heavily and almost exclusively on open flowers when they be­ came available. The experiments reported in this paper are the result of subsequent investigations to study the relative prefer­ ence exhibited by snowshoe hares for leaves, flower buds, and open flowers of the spotted catsear plant and to determine the relationship between preference and content or kind of sugar in different parts of the plant. 104 MATERIALS AND METHODS Catsear plants were collected from a clearcut Douglas-fir area in Grays Harbor County, Washington. The area of approxi­ mately 515 acres was logged in 1957-58 and planted to 2-year-old Douglas fir in 1960. Snowshoe hares severely damaged many of the trees soon after they were planted. Natural vegetation was varied and abundant. Dominant species included vine maple (Ace1· circinatum), salmon­ berry (Rubus spectabilis), western sword­ fern ( Polystichum munitum), and western bracken ( Pteridium aquilinum). Catsear occurred mainly in openings and under bracken. Three 14-acre sample plots, varying in elevation and topography, were established in hare-occupied habitat. Plant material for preference and sugar determinations was taken from each of the plots in June, 1966. Preference Tests Plants from the test plots were individ­ ually transplanted to plastic pots contain­ ing soil from the plant collection areas. Immediately before the test, dead and un­ wanted parts were removed and plants were trimmed to a uniform size, producing three categories of plants for testing: ( 1 ) plants with leaves only, (2) plants with HAnEs PREFER CATSEAR FLOWEHS leaves and flower buds, and (3) plants with leaves, flower buds, and open flowers. On each plant, there was a minimum of 20 of whatever plant parts were to be tested. Nine plants, three from each category, were randomly placed 3 ft apart in the center of a 1-acre testing pen which contained 20 hares. The hares were allowed to feed on the plants overnight in presence of natural vegetation and commercial pelleted food. At the end of the test, the plants were in­ dividually examined to determine the na­ ture and extent of hare feeding. Four tests, 7 days apart, were conducted. Sugar Analysis Samples of leaves, flower buds, and open flowers were collected from each of the plots. Leaf samples comprised only inter­ mediate, fully expanded leaves; bud and open flower samples each included 1 inch of the floral stem. Each plant part sample was taken at random from 25 plants and weighed approximately 100 g. Samples were individually sealed in glass containers and brought to the laboratory in a portable cooler. Each sample of plant material was then cut into small pieces and thoroughly mixed. Plant material was dried to constant weight at 65 C to detennine moisture and dry-matter contents. Determinations were made on paired samples taken concurrently with samples for sugar analysis. Sugars were extracted from the fresh plant tissue by adding hot alcohol at a final concentration of 80 percent and extracting in a Soxhlet apparatus for 12 hours. The alcoholic solution was then made to volume with the extracting solvent. Portions of the alcohol extracts were con­ centrated on a water bath, clarified with lead acetate, and subjected to sugar deter­ minations before and after hydrolysis ac­ cording to Hassid's eerie sulfate method • Radwan and Campbell 105 (1937) . Quantities of reducing and total sugars and those of nonreducing sugars were calculated as glucose and sucrose equivalents, respectively. The same alcoholic extracts were used for separating sugars by paper chromatog­ raphy. Portions of these extracts were par­ titioned between ·water and chloroform to remove lipids and chlorophyll. The aque­ ous phases were evaporated to dryness by warm air jets, and residues were dissolved in 1-ml amounts of distilled water. Result­ ing extracts were applied to Whatman No. 1 chromatography paper. Descending one- and two-dimensional chromatography was used (Block et al. 1958) . In the first method, chromatograms were developed twice (multiple develop­ ment technique) \Vith n-butanol: pyridine: water (6:4: 3 v/v/v) solvent. In the two­ dimensional method, the paper was first developed in the short direction with liquid phenol: water (4: 1 v/v) with 0.04 percent 8-hydroxyquinoline and then in the long direction with the upper phase of n­ butanol: acetic acid:water (25: 6:25 v/v/v) . Sugars on all dry chromatograms were located with the aniline-diphenylamine­ phosphate color reagent (Block et al. 1958: 194) . Identity of the sugar spots was estab­ lished from their RF values and by chroma­ tography with reference compounds. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Preference Techniques available for evaluating ani­ mal preference of plants are not completely without limitation. However, the method used was chosen mainly because it more closely approximated natural conditions where hares are exposed to catsear plants in association with other natural vegetation. Leaves of catsear, alone or in presence of open flowers and/or flower buds, were the least preferred part of the catsear plant 106 Fig. Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 32, No. 1, January 1968 1. (Top) Potted catsear plants with leaves only (C2), leaves and flower buds (B3), and leaves, flower buds, and open flowers (A2) just before the preference test. (Bottom) The same plants at the end of the test. (Table 1), Leaves were not utilized when they were present on the same plant with open flowers and flower buds (Fig. 1). The hares, however, nipped off a few leaf tips when open flowers were not present on the plant and a little more when leaves were the only plant part available. ·whole leaves were eaten only after all the open flowers and flower buds were consumed. This pattern of use was consistently ob­ served when the plants were left in the pen for an extra night beyond the regular length of the test. Under these conditions, leaves and remaining flower stalks were totally consumed. Although data in Table 1 indicate that open flowers and flower buds of catsear were equally preferred by the hares, dif­ ferences in preference between these two plant parts were apparent during the tests. Hares consumed open flowers first and shifted to eating flower buds after open flowers within their reach were consumed. Also, on several occasions, hares were ob­ served standing on their hind feet seeking the high open flowers, ignoring many flower buds within their reach. On the basis of these observations and data in Table 1, it seems reasonable to conclude that hares demonstrated a preference order of open flowers, flower buds, and leaves. Sugar Content Sugar contents were calculated on both the fresh- and dry-weight bases for com­ parative purposes (Table 2) . No variation (within the limits of experimental error) in amounts of either class of sugar oc­ cmTed among plants from the three sample plots whether calculations were on the HAREs PREFER CATSEAR FLOWERS Table 1. 107 Radwan and Campbell • Percent consumption of leaves, flower buds, and open flowers of spotted cofseor by snowshoe hares.* PLANT CATEGORY LEAYES FLO,VER Buns Area Area 1 Leaves, flower buds, and flowers Leaves and flower buds Leaves only 0 0 lOt 2 3 0 5t 5t 0 8t 7t 92 90 OPEN FLO"'ERS Area 2 3 1 2 3 84 100 96 94 100 85 95 * Tests were conducted overnight in a 1-acre pen with 20 hares, and all values are averages of four tests. t Consumption limited to leaf tips. fresh- or dry-weight basis. Furthermore, both methods of calculation show that the nonreducing sugar content was much lower than that o£ the reducing sugars. The total sugar content in the different parts of the plant, therefore, was primarily due to the reducing sugars present. Calculations on a fresh-weight basis show that leaves were lowest in the predominant reducing sugars but highest of all parts in the relatively minor :i1onreducing sugars. Open flowers displayed sugar levels oppo­ site of those found in the leaves, and levels of sugars in flower buds were intermediate. Amounts of reducing sugars, therefore, seemed to be a factor influencing prefer­ ence of hares for the different parts of the catsear plant. Calculations on a dry-weight basis show that leaves Vi'ere intermediate in reducing Table 2. sugars and highest in nonreducing sugars. Open flowers were highest in reducing sugars and lowest in nonreducing sugars. Flower buds were lowest in reducing sugars and intermediate in nonreducing sugars. Results of this method of calculation, there­ fore, demonstrated no correlation between sugar and preference and suggested that other factors were responsible. The different data obtained by the two methods of calculation resulted from varia­ tions in moisture content of different parts of the plant. Average moisture contents of samples from the three plots were 93.0 per­ cent, 86.3 percent, and 86.1 percent for leaves, flower buds, and open flowers, re­ spectively. We believe that calculation on a dry-weight basis, which allows accurate comparisons after excluding this variable moisture from all samples, is more appro­ priate in nutritional investigations. Here, Sugar percentages of leaves, flower buds, and open flowers of spotted catsear.* REDUCING SuaAnst NoNREDUCING SuaAns:j: ToTAL SuaARst Area Area Area PLANT PART 1 2 3 1 2 3 Fresh-weight basis: Leaves Flower buds Open flowers 0.71 1.40 2.17 0.75 1.27 2.17 0.74 1.24 2.14 0.07 0.04 0.01 0.11 0.03 0.01 0.09 0.01 0.01 10.50 10.23 15.53 10.66 9.36 15.64 10.63 9.36 15.64 1.04 0.09 O.o7 1.55 0.19 O.o7 1.30 0.10 0.05 Dry-weight basis: Leaves Flower buds Open flowers *Values are averages of two samples. t Calculated as glucose equivalents. :j: Calculated as sucrose equivalents. 2 3 0.79 1.44 2.18 0.86 1.30 2.18 0.84 1.26 2.15 11.60 10.32 15.60 12.29 9.46 15.77 12.00 9.46 15.69 108 ]oumal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 32, No. 1, ]anuar!} 1968 absolute amounts of nutrients are required. On the other hand, in preference studies taste is usually suspected to be a factor. Since, in some animals, including rabbits, "water conveys a taste stimulus" (Kare 1966:12) and because taste is known to vary vvith concentration, at least in man and some animals (Amerine et al. 1965: 89), calculation on a fresh-weight basis would seem to be the logical choice. This method more realistically includes water and expresses the chemical's concentration in the plant as encountered by the animals during the preference test (Alkon 1961:80). Consequently, we adopted the fresh-weight calculations in determining the reducing sugar factor, which seemed to influence preference ratings in this study. Kinds of Sugar Glucose and fructose were the only re­ ducing sugars present in leaves, flower buds, and open flowers of catsear. In addi­ tion, examination of the chromatograms for the nonreducing sugar fraction revealed a trace of sucrose in flower buds and open flowers and small amounts of sucrose and three other higher unidentified sugars in the leaves. The principal sugars in catsear, therefore, are the simple hexoses-glucose and fruc­ tose. Glucose (dextrose) ranks just behind sucrose in sweetness, and fructose (lev­ ulose) is the sweetest of all sugars (Biester et al. 1925:394). These two sugars are ex­ tremely important in the nutrition and metabolism of animals (Fruton and Sim­ monds 1958:493). Such properties may explain association of these reducing sugars with preference by hares for the different parts of catsear. However, perception of sweetness has not been established for hares, and some experiments with other animals have failed to show correlation between preference for food and its nutri­ tional value (Kare 1966:14). It is impos­ sible, therefore, to rule out factors other than reducing sugars, such as proteins, fats, tannins, etc. (Heady 1964:77), in explain­ ing the preference reactions of hares in this investigation, even though other investiga­ tions have shown preference of other ani­ mals for sugars and synthetic sweet ma­ terials (Plice 1952:71, Carpenter 1956:143). LITERATURE CITED ALKON, P. U. 1961. Nutritional and accept­ ability values of hardwood slash as winter deer browse. J. 'Wild!. Mgmt. 25(1):77-81. A:liiERINE, M. A., RosE MARIE PANGBORN, AND E. B. RoESSLER. 1965. Principles of sensory evaluation of food. Academic Press, Inc., New York. 602pp. Chem­ BESSER, J. F., AND J. F. vVELCH. 1959. ical repellents for the control of mammal damage to plants. Trans. N. Am. Wild!. Con£. 24:166-173. BmsTER, ALICE, MILDRED vV. \ loon, AND CECILE S. WAHLIN, 1925. Carbohydrate studies. I. The relative sweetness of pure sugars. Am. J. Physiol. 73(2):387-396. BLOCK, R. J., E. L. DURRU:M, AND G. ZWEIG. 1958. A manual of paper chromatography and paper electrophoresis. 2nd eel. Academic Press, Inc., New York. 710pp. CARPENTER, J. A. 1956. Species differences in taste preferences. J, Comp. Physiol. Psycho!. 49(2):139-144. FRUTON, J. S., AND SoFIA SrM IONDS. 1958. General biochemistry. John vViley and Sons, Inc., New York. 1,077pp. HASSID, vV. z. 1937. Determination of sugars in plants by oxidation with ferricyanide and eerie sulfate titration. Ind. Eng. Chem. (Anal. eel.) 9(5):228-229. HEADY, H. F. 1964. Palatability of herbage and animal preference. J. Range Mgmt. 17(2): 76-82. KARE, M. R. 1966. Taste perception in animals. Agr. Sci. Rev. 4(1):10-15. .lviooRE, A. W. 1940. Wild animal damage to seed and seedlings on cut-over Douglas fir lands of Oregon and Washington. U. S. Dept. Agr. Tech. Bull. 706. 28pp. MuNGER, T. T. 1943. Vital statistics for some Douglas-fir plantations. J. Forestry 41(1): 53-56. PLICE, M. J. 1952. Sugar versus the intuitive choice of foods by livestock. J. Range Mgmt. 5(2):69-75. Received for publication August 3, 1967.