Proof Delivery Form - Special phi Supp 66/PHS99029 Philosophy

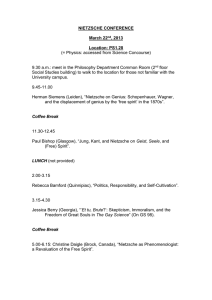

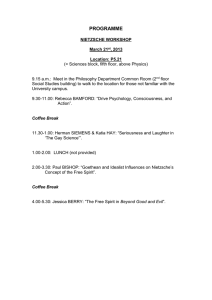

advertisement