ns39_002.pod 201 07-05-28 10:17:17 -mt- mt Keith Ansell-Pearson

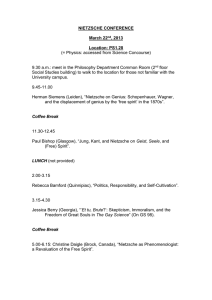

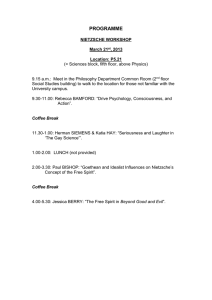

advertisement