WATER AND LIVELIHOODS: A PARTICIPATORY ANALYSIS OF A MEXICAN

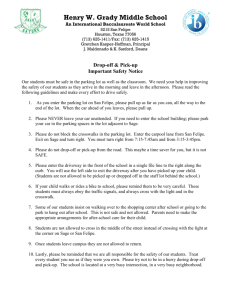

advertisement