SCRIPPS DISCOVERS

advertisement

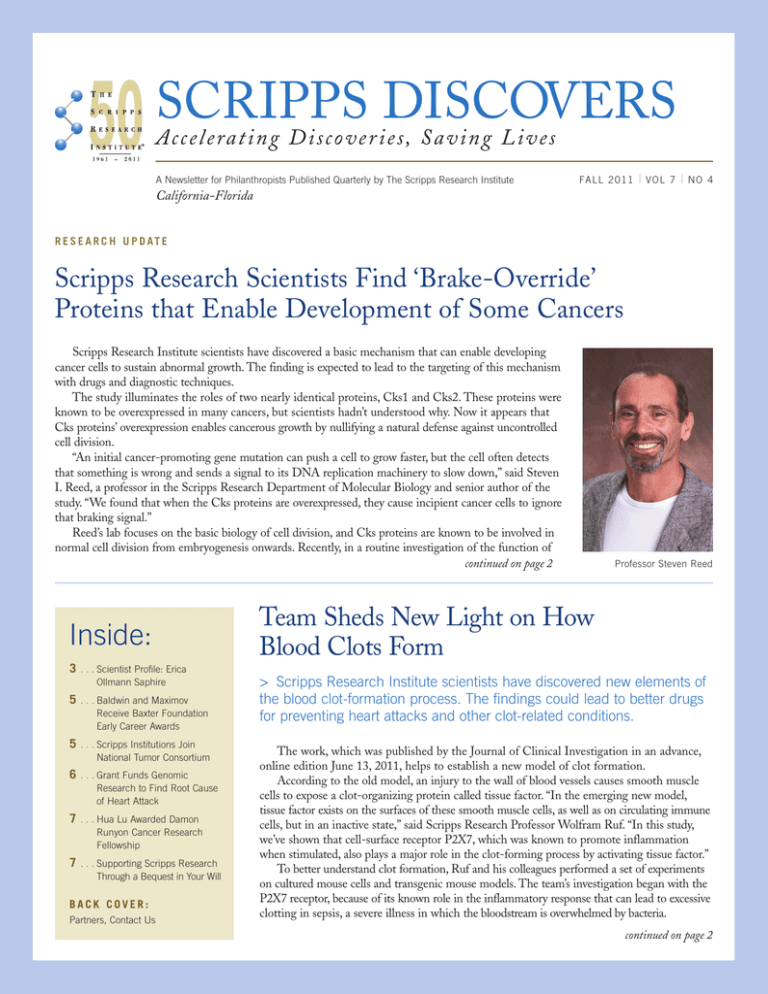

SCRIPPS DISCOVERS Accele rating Discove r ies, S a ving L ives A Newsletter for Philanthropists Published Quarterly by The Scripps Research Institute FA L L 2 0 1 1 | VOL 7 | NO 4 California-Florida R E S E A R C H U P D AT E Scripps Research Scientists Find ‘Brake-Override’ Proteins that Enable Development of Some Cancers Scripps Research Institute scientists have discovered a basic mechanism that can enable developing cancer cells to sustain abnormal growth. The finding is expected to lead to the targeting of this mechanism with drugs and diagnostic techniques. The study illuminates the roles of two nearly identical proteins, Cks1 and Cks2. These proteins were known to be overexpressed in many cancers, but scientists hadn’t understood why. Now it appears that Cks proteins’ overexpression enables cancerous growth by nullifying a natural defense against uncontrolled cell division. “An initial cancer-promoting gene mutation can push a cell to grow faster, but the cell often detects that something is wrong and sends a signal to its DNA replication machinery to slow down,” said Steven I. Reed, a professor in the Scripps Research Department of Molecular Biology and senior author of the study. “We found that when the Cks proteins are overexpressed, they cause incipient cancer cells to ignore that braking signal.” Reed’s lab focuses on the basic biology of cell division, and Cks proteins are known to be involved in normal cell division from embryogenesis onwards. Recently, in a routine investigation of the function of continued on page 2 Inside: 3 . . . Scientist Profile: Erica Ollmann Saphire 5 . . . Baldwin and Maximov Receive Baxter Foundation Early Career Awards 5 . . . Scripps Institutions Join National Tumor Consortium 6 . . . Grant Funds Genomic Research to Find Root Cause of Heart Attack 7 . . . Hua Lu Awarded Damon Runyon Cancer Research Fellowship 7 . . . Supporting Scripps Research Through a Bequest in Your Will BACK COVER: Partners, Contact Us Professor Steven Reed Team Sheds New Light on How Blood Clots Form > Scripps Research Institute scientists have discovered new elements of the blood clot-formation process. The findings could lead to better drugs for preventing heart attacks and other clot-related conditions. The work, which was published by the Journal of Clinical Investigation in an advance, online edition June 13, 2011, helps to establish a new model of clot formation. According to the old model, an injury to the wall of blood vessels causes smooth muscle cells to expose a clot-organizing protein called tissue factor. “In the emerging new model, tissue factor exists on the surfaces of these smooth muscle cells, as well as on circulating immune cells, but in an inactive state,” said Scripps Research Professor Wolfram Ruf. “In this study, we’ve shown that cell-surface receptor P2X7, which was known to promote inflammation when stimulated, also plays a major role in the clot-forming process by activating tissue factor.” To better understand clot formation, Ruf and his colleagues performed a set of experiments on cultured mouse cells and transgenic mouse models. The team’s investigation began with the P2X7 receptor, because of its known role in the inflammatory response that can lead to excessive clotting in sepsis, a severe illness in which the bloodstream is overwhelmed by bacteria. continued on page 2 Cancer, CONTINUED Cks proteins in cells, Reed’s team used a chemical known as thymidine to temporarily halt the cell division process, to artificially synchronize the growth of two different groups of cells—one with normal Cks expression, and the other with Cks overexpression. To the researchers’ surprise, the Cks-overexpressing cells failed to stop dividing. “That was a serendipitous observation,” said Reed. “It led us to hypothesize that these Cks proteins, when overexpressed, are preventing cells from responding to a normal growth-braking signal.” As a dividing cell unravels its chromosomes, replicates them, and becomes two new cells, it encounters safety “checkpoints,” at which the cell division process should stop if the correct signals are not in place. Thymidine inhibits cell division by producing a stop signal at what is known as the “intra-S-phase checkpoint.” But somehow, Cks overexpression causes cells to speed past that checkpoint. Reed and his team observed that the checkpoint-override effect turned out to require a Cks expression level three to four times higher than normal—the same Cks overexpression level they observed in cell lines derived from human breast tumors. “That’s probably not a coincidence,” said Reed. Blood Clots, Reed’s team created a simple model of Cks’s function in cancer, inserting a mutant, cell-division-promoting “oncogene” into human breast-derived cells. The oncogene’s protein product, known as cyclin E, pushed the cell towards uncontrolled division, which—as expected—triggered an intra-S-phase checkpoint response, so that the rate of cell division went sharply down. “When we overexpressed Cks, the cell division rate went back up again,” said Reed. Sampling real breast cancer cells from a tumor bank, Reed’s team found that cells with high levels of cyclin E also tended to have high levels of Cks. Since neither protein directly influences the level of the other, the implication was that an initial oncogenic overactivation of cyclin E must in most cases be followed by Cks overexpression to keep a cell on the path to full-blown cancerous growth. “The statistical link between the cyclin-E and Cks levels was so strong that it could not have been a coincidence,” said Reed. Cks’s cancer-enabling potential appears to be a broad one. When Reed’s team looked at incipient cancer cells whose growth was driven by a different oncogene, h-Ras, they again found that the oncogene provoked checkpoint-dependent slower growth, whereas Cks overexpression partially nullified it and allowed cell division to proceed almost as normal. In recent years, other researchers have noted that an initial oncogene activation can trigger a slightly different kind of growth arrest in cells. The phenomenon, known as oncogene-induced continued on page 4 CONTINUED Normally, when cells are damaged, they release large quantities of energystorage molecules known as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Previous research had hinted that when this freed ATP encounters passing immune cells, it serves as a damage signal, stimulating the immune cells’ P2X7 receptors and causing the release of “microparticles” exposing the clot-promoting tissue factor. The new study showed that ATP can affect P2X7 receptors on both immune cells and smooth muscle cells. To confirm the significance of the P2X7 receptor in the clot-forming process, the team bred transgenic mice that lacked functional P2X7 receptors, and found that these P2X7-knockout mice failed to form stable arterial blood clots when the vessel wall was exposed to a clot-inducing substance. Importantly, these mice did not suffer from uncontrollable bleeding. 2 | SCRIPPS DISCOVERS FA L L 2 0 1 1 “This suggests that clot-preventing drugs targeting the P2X7 pathway might not have unacceptable side effects,” said Ruf. In the cell experiments, the team found that the cascade of molecular events following P2X7 stimulation alters the activity of a thiol-targeting enzyme known as protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), which Ruf 's previous studies had implicated as a possible activator of tissue factor. In the new study, the scientists demonstrated the importance of PDI in this process by showing that they could block clot formation in normal mice with anti-PDI antibodies. Targeting the top of the clot-formation pathway by blocking the P2X7 receptor might have even broader beneficial effects, since the activation of this receptor occurs in a number of inflammatory disorders. “Cardiovascular disease and heart attacks are caused by chronic inflammation as well as clot formation,” said Ruf, “so possibly P2X7 is a major explanation for the link between inflammation and thrombosis, as well as a good target for preventing these conditions.” This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association. Professor Wolfram Ruf SCIENTIST PROFILE Erica Ollmann Saphire: Fighting Deadly Viruses in the Deep Reaches of the African Jungle > Biomedical researchers in search of knowledge about the workings of the human body and the viruses and diseases they fight typically make their discoveries in labs. But for Scripps Research Associate Professor Erica Ollmann Saphire, the key to understanding deadly viruses is meeting them in their den – the deep reaches of the African jungle. rica has several times traded her climate-controlled La Jolla lab for the 95 degree humidity of the West African jungle, where she has tracked the Ebola virus, Lassa hemorrhagic fever, and other hemorrhagic fevers, such as Marburg virus – the subjects of her research for the past eight years. “It is an opportunity to see where these viruses live,” said Erica. “In the lab, we use biochemistry and biophysics to visualize and understand their component molecules. But these molecules are made this way so they can function not in a lab, but in a rainforest, cave or hut. In order to fully understand their function, you have to put yourself in that rainforest, cave and hut. You can do great science in the lab but the real goal is to translate this science into use in the real world.” Back in her lab, Erica applies this close-up look at these viruses to her efforts to characterize them on the molecular level. “Our goal is to get a road map for how to understand and conquer these viruses, which have been largely undefeatable,” said Erica. The Ebola virus is among the more horrific known to humankind, and there is currently no cure for Ebola hemorrhagic fever, which inflicts a death rate as high as 90 percent of those infected. It spreads when people come into contact with the bodily fluids of an infected individual. Symptoms first include a sudden fever, headache, and sore throat, then progress to vomiting, diarrhea, rash, and kidney and liver failure. In the final stages, massive hemorrhaging causes heavy bleeding from body openings and internal organs. E Erica made headlines as the woman who broke open the secrets of the Ebola virus. Her breakthrough study on Ebola appeared on the cover of the journal Nature, lifting the veil from the virus’s spike-shaped protein, a critical step in understanding how Ebola works and an essential step for any potential development of a treatment or a vaccine. The Ebola virus glycoprotein itself, the one thing that is necessary for attaching to and infecting a host, has been a therapeutic target for more than 10 years. But because the structure was unknown, no one knew how to take advantage of it. The structure uncovered by Erica’s lab gives researchers weaknesses to target in developing any potential therapeutic. In her five-year quest to uncover the structure of the key protein that resides on the surface of the Ebola virus and allows it to enter human cells, Erica and her colleagues produced more than 50,000 crystals, as part of the team’s use of a technique called x-ray crystallography to determine the atomic structure of molecules. “We uncovered chinks in the virus’s elaborate armor that we can target specific antibodies against,” said Erica. Support for Erica’s work on this research was provided partially by a Career Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, as well as funding from the Skaggs family to recruit and support postdoctoral fellows. In the past, she has also received private funding for her work on Dengue Virus through a New Initiatives Award in Global Infectious Disease from The Ellison Medical Foundation. “Private philanthropic support has provided us with the seed money for risky projects,” said Erica. “With these funds, we’ve been able to do the big initial work and make discoveries that then set up the next ten years for federal funding.” On her most recent trip to Africa, Erica visited the hospital with which her lab is collaborating to investigate the virus that causes Lassa hemorrhagic fever. The goal of this joint initiative is to provide field diagnostics as well as critical templates for therapeutics and vaccines by understanding how Lassa virus infects cells. Her trip was part of a project with Tulane University aimed at developing new ways to treat and prevent Lassa fever. Lassa fever, a huge public health threat, is an often deadly viral disease that threatens hundreds of thousands of people annually in West Africa. In some areas of Sierra Leone, up to 16 percent of people admitted to hospitals have Lassa fever. Lassa fever is also associated with occasional epidemics, during which the fatality rate can reach 50 percent. “If you catch Lassa early enough, it’s treatable,” said Erica, “but you need cheap, fast, and simple diagnostics. Local hospitals only have electricity every other day, the local lab technicians might not be well trained, the country was ravaged by civil war, roads can be impassable, few vehicles are available, and the average working person ears far less than $100 a year. If the test costs more than pennies, is complicated or can only be run in a laboratory, it’s not going to be useful.” Erica and her team have learned how to make recombinant protein both inexpensively and cleanly, and are working to develop it into a diagnostic, somewhat like a pregnancy test dipstick. This early diagnostic allows the fever to be identified and treated in time to save the patient’s life. SCRIPPS RESEARCH INSTITUTE | 3 Saphire, CONTINUED “By looking at the structure of the core nucleoprotein of Lassa, we discovered a whole new function of the protein that no one knew it had before,” said Erica. “This is the first step in being able to design drugs to combat the virus.” The village chief of the village of Yawei was so grateful for the team’s work on trapping rodents that helped rid their village of Lassa, that he gave them a goat, a prized possession that normally costs a year’s salary, as a gift in gratitude. “The fact that the chief and village were so thankful for our work is a huge motivator for our team,” said Erica. “It gives our work more meaning than just a paper in a journal.” Born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and raised in Austin, Texas, Erica wanted to be a journalist in high school. Journalism held the allure of a career with the potential of seeing new things, maybe experiencing some adventure, and having a decent chance to figure things out. Her parents were teachers and she remembers they often spent their summers traveling to national parks. In college at Rice University in Houston, is where she first took up science, studying biochemistry in the lab and the ecology of East Texas wetlands in the field for species restoration and food production. Erica continued to pursue science in graduate school, enrolling in what is now the Scripps Research Kellogg School of Science and Technology due to the program’s focus on research and discovery. Working in the Scripps Research laboratory of Professor Ian Wilson, she took on a difficult and ambitious project involving another infamous and deadly virus – human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) – as part of a larger effort to help develop a vaccine against AIDS. After she received her Ph.D. in 2000, Erica chose to stay at Scripps Research where she now heads her own lab. Erica was recently honored at the White House where she received a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers, the highest honor bestowed by the United States government for young professionals at the outset of their independent research careers. Associate Professor Erica Ollmann Saphire with Stu the Goat Cancer, The award winners are selected based on two criteria: innovative research at the frontiers of science and technology, and community service demonstrated through scientific leadership, education, or community outreach. Erica credits her fellow faculty members at Scripps Research, as well as the postdoctoral fellows and graduate students working in her lab with much of her success. “My faculty colleagues are bright, interesting, and collaborative – they’re all doing important work and are on top of their fields. They’re willing to share ideas, which inspires me,” said Erica. “And our students and postdocs here work extremely hard and share my mission to defeat these viruses – they’re willing to put in the extra work to make our discoveries possible.” C O N T I N U E D F R O M PA G E 2 cellular senescence, is believed to underlie the slow or stopped growth of skin moles and some benign cancers. “It has been shown that this induced senescent state depends in part on the persistent activation of cell-cycle checkpoints, so presumably it is related to the process affected by Cks,” said Reed. Reed and his team are now trying to determine the precise molecular events through which Cks proteins exert their checkpointnullifying effect in cancer. At the same time, they are looking for ways to use their new knowledge against Cks-overexpressing cancers. The most direct strategy would be to treat cancer, or prevent it in people with inherited predispositions, simply by using a drug to reduce the activity of Cks proteins. “We know that we can delete half of the Cks genes from mice without any deleterious effects, and this reduces the frequency of tumor formation,” said Reed. “So the chances are we could find a way to reduce Cks proteins’ activity enough to prevent their checkpoint-override effect while still allowing their essential cell functions.” 4 | SCRIPPS DISCOVERS FA L L 2 0 1 1 AWARDS AND HONORS Kristin Baldwin and Anton Maximov Receive Baxter Foundation Early Career Awards ssistant Professors in the Department of Cell Biology Kristin Baldwin and Anton Maximov have been named recipients of the 2011 Baxter Foundation Early Career Award. The award is funded by a Donald E. & Delia B. Baxter Foundation endowment to Scripps Research. The two Department of Cell Biology investigators will use the award to fund risky projects of potentially high impact that have not yet been funded by more traditional mechanisms. Baldwin’s lab aims to improve stem cell and reprogramming technologies to better understand brain development and generate models of neurological disease. Maximov’s lab seeks to define the basic mechanisms underlying synaptic development and function, and to elucidate the links between synaptic abnormalities and heritable disease. The two laboratories, situated nearby in the Dorris Neuroscience Center, will use the Baxter Awards to enhance existing synergies between the research groups. Founded in 1959, the Baxter Foundation was established initially in memory of Donald Baxter, who developed and manufactured the first commercially prepared intravenous solutions. A Assistant Professor Kristin Baldwin Assistant Professor Anton Maximov Scripps Institutions Join National Tumor Consortium he Scripps Research Institute, Scripps Health, and Scripps Translational Science Institute (STSI) have announced they have joined a national consortium of research institutions headed by The Jackson Laboratory ( JAX) that is building a library of primary human tumors with the goal of developing highly targeted cancer therapies. “By joining this consortium, we will contribute to and share in a tumor library that will vastly exceed what any institution could build on its own,” said Nicholas J. Schork, professor at Scripps Research and director of bioinformatics and biostatistics at STSI. “This shared resource ultimately will greatly expand research capacity for all consortium members, with the goal of accelerating drug development for individualized approaches to each type of tumor.” JAX launched the Primary Human Tumor Consortium in 2009. Consortium members provide solid human tumor samples to JAX, which performs their initial genomic characterization and grafts them into mouse models for scientific study. Consortium scientists then have access to the models to conduct research on how to better understand and treat cancer, including the potential for tumor-specific therapies. Mouse models that can accept newly resected human tumors offer a highly productive way to develop and test cancer treatments. Mouse models of virtually any kind of cancer can be developed, providing a more individualized approach to finding new treatments. This approach stands in stark contrast to the standard way of discovering new therapies for cancer, which relies on the use of tumor cell lines. The tumor cell-line approach can be problematic, since genetic mutations naturally occur as those cells divide and reproduce. Consequently, the cells may drift into a different T genetic profile and any treatments designed to target the original tumor won't work. Also, the cell-line approach provides insights into which therapies are ineffective, but doesn't predictably prove which ones are effective. “The biomedical research community needs a common, readily accessible resource to support this vital effort,” said JAX Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Chuck Hewett. “No single cancer center has a sufficiently broad patient population to meet this need, so we must work together.” Located at The Jackson Laboratory’s JAX-West facility in Sacramento, California, the Primary Human Tumor Consortium seeks additional health care and research partners to speed the development of this tumor library resource. Other participating institutions outside San Diego include the University of Florida, the Swedish Neuroscience Institute in Seattle, and UC Davis Cancer Center. To date, the consortium has engrafted 172 tumors, with tumor sites including prostate, pancreas, lung, kidney, colon, breast, brain and bladder. Professor Nicholas Schork SCRIPPS RESEARCH INSTITUTE | 5 $7.9 Million NIH Grant Funds ‘Disease in a Dish’ Genomic Research to Find Root Cause of Heart Attack > Researchers looking to find a root cause for heart attacks and coronary artery disease will soon begin using a novel investigative approach as they work toward preventing the nation's number one killer. he National Institutes of Health (NIH) has awarded a $7.9 million grant to the Scripps Translational Science Institute (STSI) of The Scripps Research Institute and Scripps Health in San Diego and Sangamo BioSciences (NASDAQ: SGMO) of Richmond, California, to conduct the nation’s first-ever, heart-based “disease in a dish” research. The study will involve the use of induced pluripotent stem cells (non-embryonic stem cells created from mature cell types, such as skin cells) to recreate participants’ own heart artery-lining cells in a dish, along with genome-editing technology aimed at potentially directing certain cells away from a disease state. T Medical research confirms that the human genome’s 9p21 “gene desert” region, which everyone possesses, is strongly linked to people’s risk of developing heart disease. But researchers don’t understand what takes place in this trouble spot that causes some people’s cells to eventually become diseased. This portion of genetic code is known as a “gene desert” because there are no genes in this region. “We’re trying to figure out for the first time how this region works and which other parts of the genome or genes it’s interacting with to make some people’s cells become diseased,” said Scripps Research Professor of Translational Genomics Eric J. Topol, the study’s principal investigator and director of STSI. In the study, scientists will recreate artery-lining cells for two distinct patient groups, each totaling approximately 1,000 people. The first group includes those who already have coronary artery disease, which is a precursor to heart attack. The second cohort comprises those who have lived to at least age 80 without any heart disease or other major illnesses. “We’ll take people whose 9p21 region of the genome says they’re at risk for coronary artery disease, and then compare the stem cells from that individual to a healthy elderly person who may also have risk in that region, but somehow doesn’t have the disease,” said Samuel Levy, the study’s lead investigator, director of genomic sciences with STSI and professor of molecular and experimental medicine at Scripps Research. “The crux of our research is to figure out which genes, or which other parts of the genome, are interacting with the 9p21 region. There are no genes in the 9p21 region, which is a big part of our challenge.” The “disease in a dish” heart study brings together two emerging research strategies that, to date, have largely developed separately —induced pluripotent stem cells to create relevant cells and a sophisticated genome-editing technology, which acts like scissors 6 | SCRIPPS DISCOVERS FA L L 2 0 1 1 to cut and replace pieces of the genome. The research will also leverage extensive data from genome-wide association studies. “Genome editing allows us to do an experiment no one has ever tried; that is, if you change someone’s genetics, can you make their cells revert away from acquiring a disease?” said Levy. “Using zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) that act like molecular scissors, we can actually take this risk region out of a person’s genome and see what happens to his cells if that region is present or absent. This editing allows us to basically recreate the disease or take it away.” Scientists will take skin or blood cells from participants and reprogram them to create induced pluripotent stem cells, which have the capacity to become any cell type in the body. These stem cells then will be transformed into three different types of heart artery-lining cells: smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and cardio myocytes. Researchers will characterize participants’ artery-lining cell types as a way of trying to understand how someone with the 9p21 allele of risk ultimately goes on to acquire cells that are diseased. Once scientists understand the cells’ underlying biology, they’ll employ a genome-editing process using zinc finger proteins to cut the genome and replace parts of it with DNA with a different sequence. This will enable researchers to decipher how this gene desert region functions. Learning the root defect in the genome would open the door to potentially developing new drugs or identifying existing ones that could help a person’s cells revert away from the path of developing a heart attack or coronary artery disease later in life. According to Topol, this study will address the biggest deficiency in genomics today. “We don’t know the so-called functional genomics,” he said. “We only know there’s this zip code in the genome that’s a problem spot, but we don’t know what’s going on in this zip code of hundreds of thousands of letters. We don’t know which is the offending letter or group of letters. Genome editing will allow us to edit each one and analyze which ones are the culprits.” Professor Eric Topol Hua Lu Awarded Damon Runyon Cancer Research Fellowship Hua Lu, research associate in the Schultz lab, has been named a 2011 Damon Runyon Fellow, a prestigious award presented by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation to recognize earlycareer researchers. According to the foundation, the fellowship “encourages the nation’s most promising young scientists to pursue cancer research by providing them with independent funding to work on innovative projects.” The 18 newly announced fellows each receive a three-year grant to pursue their research. A research associate in the laboratory of Professor Peter G. Schultz, Lu has focused his scientific investigation on developing antibody-drug conjugates that can specifically recognize and kill acute myeloid leukemia cancer cells. Lu aims to generate highly specific ADCs to attack tumor cells without harming normal cells. His work may lead to identifying new clinical candidate drugs. Since its founding in 1946, the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation has invested more than $235 million in funding more than 3,250 young scientists. Among past foundation fellows are eleven Nobel Prize winners, heads of cancer centers, and leaders of renowned research programs, according to the foundation. Fewer than 10 percent of fellowship applicants are funded in the competitive award program. Hua Lu Supporting Scripps Research Through a Bequest in Your Will Remembering us in your will is the most enduring statement you can make about your belief in our mission. Here you will learn how easy it is to extend the support you have offered throughout your lifetime for years to come. Q – I want to remember Scripps Research in my will; how do I accomplish this? A – The process of making a provision in your will for The Scripps Research Institute is simple. You can include a charitable bequest when you create your will, or you may add or update a bequest later with a codicil, a formal amendment to your will. With a bequest, you can give away property, securities or real estate without worrying about whether you will need those assets, because the giving of them won’t actually take place until after your lifetime. Q – What are the benefits of making a bequest? A – Bequests are: · Easy. A few sentences in your will or living trust complete the gift. · Revocable. Until your will or trust goes into effect, you are free to alter your plans. · Versatile. You can bequeath a specific item, an amount of money, a gift contingent upon certain events or, most common, a percentage of your estate. Q – How do I put a bequest in place? A – Take these three simple steps: · Decide what amount or percentage you want to give. · Take the sample bequest language (listed below) to your estate planning attorney to add to your will. · Notify us of your intention, if you would like (we will honor your preferences regarding anonymity), so our staff can thank you for your future gift, include you in The Scripps Legacy Society, and keep you informed of ongoing activities. Selected Language to Remember Us in Your Will If you would like to support our mission after your lifetime, ask your estate planning attorney to add this suggested wording to your will or living trust: Example of unrestricted bequest language: I give (insert dollar amount, property to be given, percentage of the estate or “the remainder of my estate”) to The Scripps Research Institute, a nonprofit corporation, tax identification number 33-0435954, headquartered at 10550 N. Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037, for its general use and purposes. Example of restricted bequest language: I give (insert dollar amount, property to be given, percentage of the estate or “the remainder of my estate”) to The Scripps Research Institute, a nonprofit corporation, tax identification number 33-0435954, headquartered at 10550 N. Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037, to support (insert designation or purpose) at The Scripps Research Institute. To learn more about supporting Scripps Research through a gift in your will, please contact William Burfitt in our California office, (858) 784-2037 or burfitt@scripps.edu, or Alex Bruner in our Florida office, (561) 228-2013, or abruner@scripps.edu, at no obligation. We would also be happy to discuss how your gift will help treat devastating diseases. SCRIPPS RESEARCH INSTITUTE | 7 Partners 1 A private event for over 75 clients of PNC Wealth Management, Palm Beach, was held recently on the Scripps Florida campus. Attendees enjoyed a short presentation on aging by Professor Roy Smith, founding chairman of the Department of Metabolism and Aging, an overview of Scripps Florida from Barbara Noble, a behind-the-scenes tour of several research laboratories, and a lavish luncheon in the Founders Room. PNC Wealth Management is a longtime, dedicated supporter of Scripps Research. Pictured (l to r) are Mark Stevens, Executive Vice President and Managing Director of PNC Wealth Management, with his wife, Sonya; and Chairman Roy Smith, Ph.D., with his wife, Jane. (top photo) 2 This year, Scripps Florida’s high school and undergraduate summer interns represented thirteen Palm Beach County high schools, and five colleges and universities from across the United States. The undergraduate Kenan Fellows are seeking degrees in the sciences and are past participants of the six-week high school program. This summer, they returned to Scripps Florida laboratories to complete a ten-week summer research internship. Now in its seventh year, the Kenan Fellows program at Scripps Florida is made possible through the generous support of The William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust, and lead by Deborah Leach-Scampavia, Director of Education Outreach Programs. The 2011 Kenan Fellows are pictured here. (bottom photo) 3 The Saul and Theresa Esman Foundation has made a new pledge for $832,000 to fund a postdoctoral fellowship under the direction of Professor Philip LoGrasso in the Department of Molecular Therapeutics at Scripps Florida. When combined with prior gifts, the Foundation becomes our newest $1 million benefactor. This gift is an example of the ardent commitment by Theresa Esman (pictured above) and the Esman Foundation to basic science research. Scripps Research is now the leading recipient of the Foundation’s philanthropic support of disease research. (middle photo) Contact Us: • For more information about Scripps Research, visit our web page at www.supportscrippsresearch.org • To learn more about supporting Scripps Research’s cutting-edge research, please contact: CALIFORNIA (858) 784.2037 or (800) 788.4931 burfitt@scripps.edu FLORIDA (561) 228.2013 abruner@scripps.edu