AE U R The Key Elements of

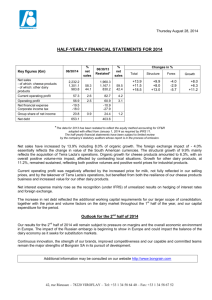

advertisement