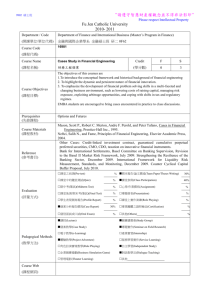

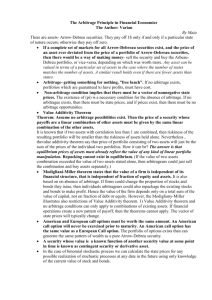

A S : P

advertisement