Document 12728512

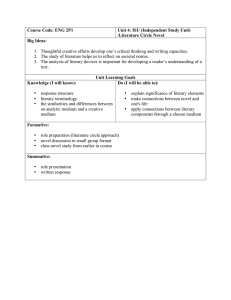

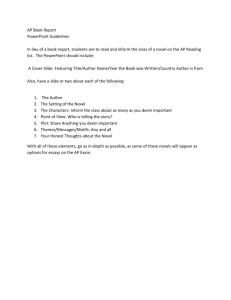

advertisement