DANCE AND DRAMA AWARDS SCHEME EVAULATION PROJECT – PHASE II 1

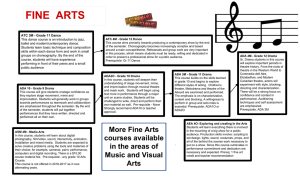

advertisement