Document 12702833

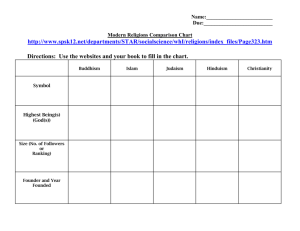

advertisement