MEASURING MILITARY CAPABILITY

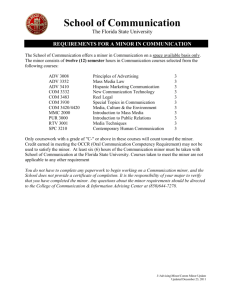

advertisement