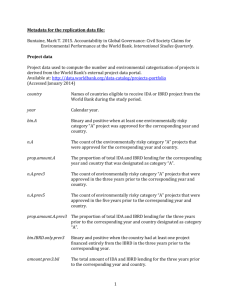

Document 12697866

advertisement