Making Inferences and Drawing Conclusions

advertisement

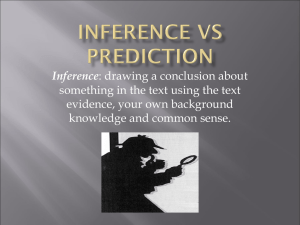

Making Inferences and Drawing Conclusions A text does not contain a meaning Readers construct meaning by what they take the words to mean and how they process sentences to find meaning. Readers draw on their knowledge of the language and of conventions of social communication. They infer unstated meanings based on social conventions, shared knowledge, shared experience, or shared values. They make sense of remarks by recognizing implications and drawing conclusions. Readers read ideas more than words, and infer, rather than find, meaning Inferences are evidence-based guesses. They are the conclusions a reader draws about the unsaid based on what is actually said. Inferences drawn while reading are much like inferences drawn in everyday life. If your best friend comes in from a blind date and looks utterly miserable, you would probably infer the date was not a success. Reading Tips: • 1. Make sure your inferences rely mainly on the author’s words rather than your own feelings or experience. Your goal is to read the author’s mind, not invent your own message. • 2. Check to see if your inference is contradicted by any statements in the paragraph. If it is, it is not an appropriate or useful inference. • 3. If the passage is a tough one, check to see if you can actually identify the statements that led you to your conclusion. This kind of close reading is a good comprehension check. It will also help you remember the material. Consider the following statement: “The Senator admitted owning the gun that killed his wife.” What does it mean? a. b. c. d. What about this? A man and his son are driving in a car. The car crashes into a tree, killing the father and seriously injuring his son. At the hospital, the boy needs to have surgery. Upon looking at the boy, the doctor says (telling the truth), "I cannot operate on him. He is my son.“ How can this be? Decide on your answer before reading further. Implications For Reading All reading is an active, reflective, problem-solving process. We do not simply read words; we read ideas, thoughts that spring from the relationships of various assertions. The notion of inference equations is particularly powerful in this regard. Readers can use the notion of inference equations to test whether or not the ingredients for a given inferences are indeed present. To show lying, for instance, a text must show that someone made a statement that they knew was incorrect and that they made that assertion with the specific purpose of deception. If they did not know it was wrong at the time, it’s an error, not a lie. If they did not make the statement for the specific purpose of deception, we have a misstatement, not lying. Interpreting what you read Because writers don't always say things directly, sometimes it is difficult to figure out what a writer really means or what he or she is really trying to say. You need to learn to "read between the lines" - to take the information the writer gives you and figure things out for yourself. You will also need to learn to distinguish between fact and opinion. As you read an author's views, you should ask yourself if the author is presenting you with an established fact or with a personal opinion. facts • can be verified in reference books, official records, and so forth. • are expressed in concrete language or specific numbers. • once verified, are generally agreed upon by people. opinions • are often expressed as comparisons (more, strongest, less, most, least efficient or but) • are often expressed by adjectives (brilliant, vindictive, fair, trustworthy): • often involve evaluations: • are often introduced by verbs and adverbs that suggest some doubt in the writer's mind. (seems, appears, probably)