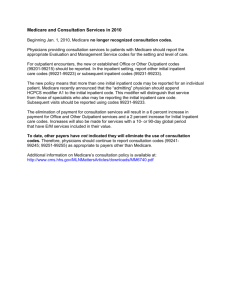

W O R K I N G Inpatient Hospital Services

advertisement