W O R K I N G Medicare Payment

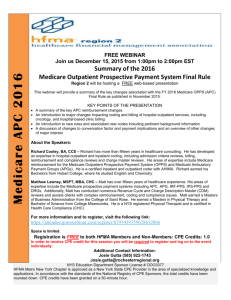

advertisement