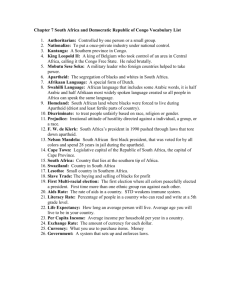

THE SOUTH AFRICAN RETROSPECTIVE CASE Pearl-Alice Marsh and Thomas S. Szayna INTRODUCTION

advertisement