RULE OF LAW IN TIMOR-LESTE

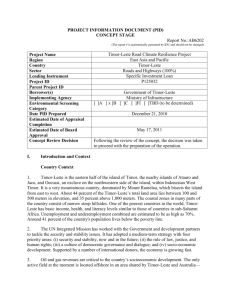

advertisement