Rigour and Responsiveness in Skills April 2013

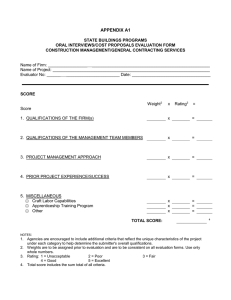

advertisement