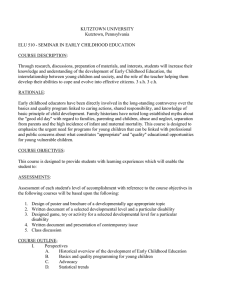

Social and emotional skills in childhood and their long-term

advertisement