College on the Cheap: Costs and Benefits of Community College Denning

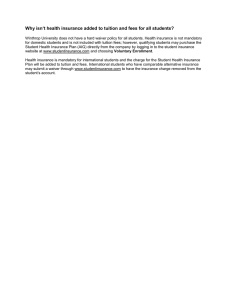

advertisement