National Defense in a Time of Change DISCUSSION PAPER 2013-01

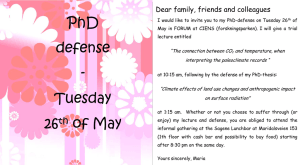

advertisement