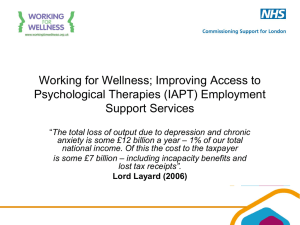

Psychological Wellbeing and Work

advertisement