E R NVIRONMENTAL EPORT

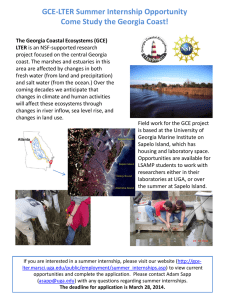

advertisement