NOTE: REFERENCES TO ORS 279 AND BOLI REGULATIONS CONTAINED... DO NOT REFLECT ANY CHANGES OCCURING SUBSEQUENT TO THE PUBLICATION

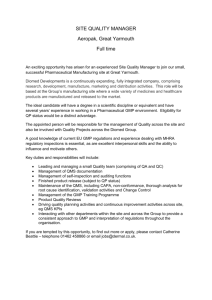

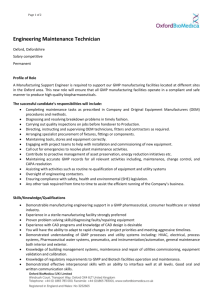

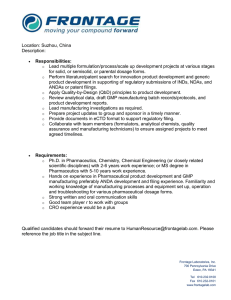

advertisement