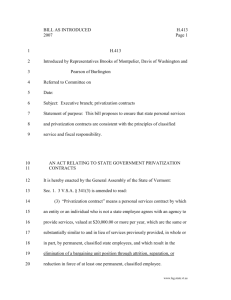

W P N 6

advertisement