ORIENTED STRAND BOARD HOME SIDING LITIGATION: IN RE LOUISIANA-PACIFIC INNER-SEAL SIDING PROLOGUE

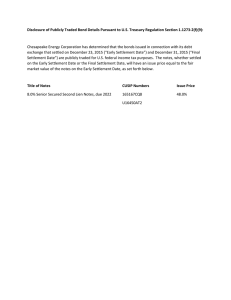

advertisement