The Role and Impact of User Representation and October 2008

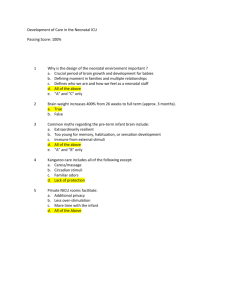

advertisement