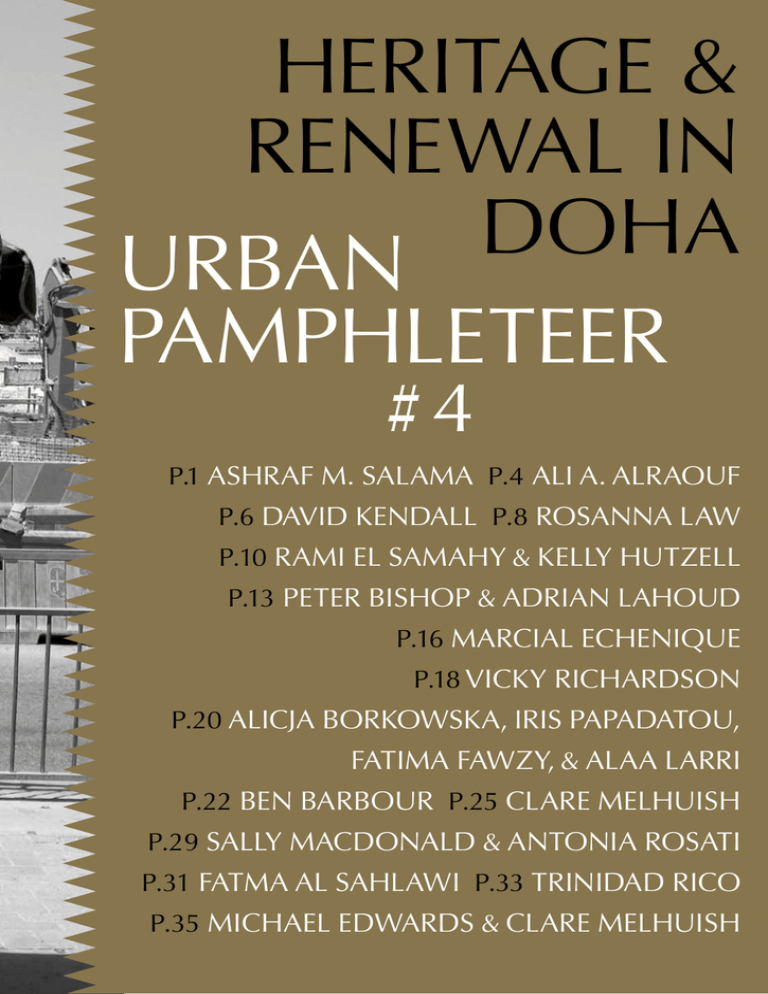

HERITAGE & RENEWAL IN DOHA URbAN

advertisement