Innovation Models Enabling new defence solutions and enhanced

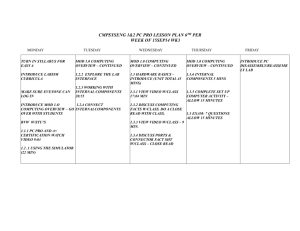

advertisement