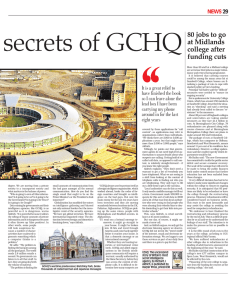

Tapping in to the secrets of GCHQ 28 NEWS

advertisement

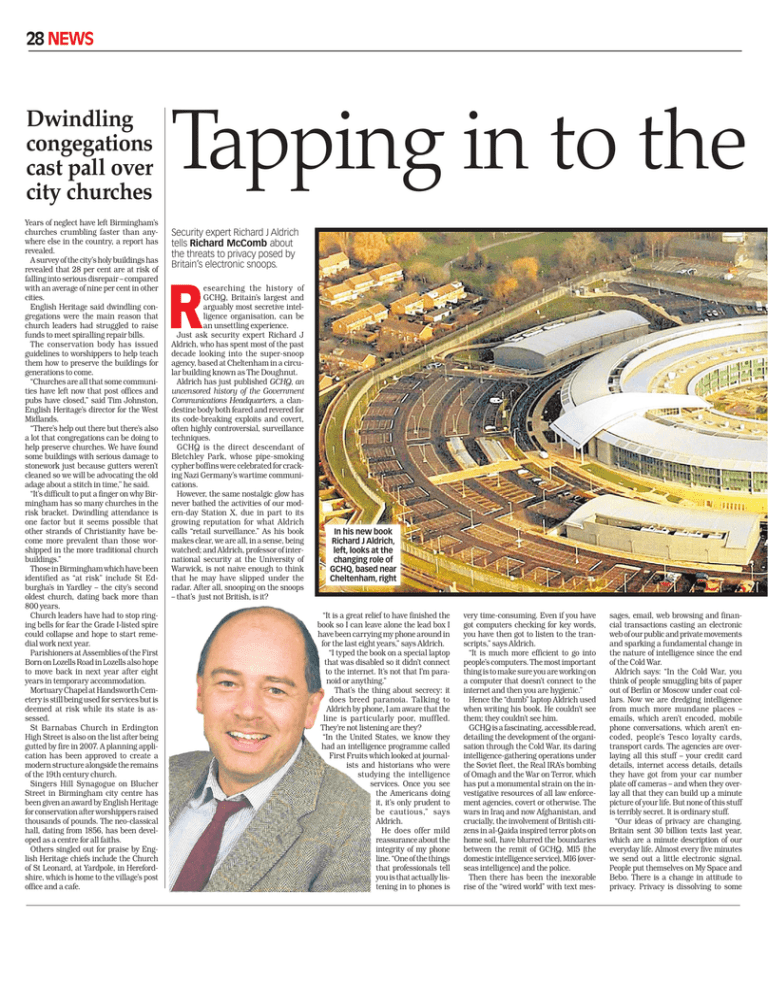

28 NEWS Dwindling congegations cast pall over city churches Years of neglect have left Birmingham’s churches crumbling faster than anywhere else in the country, a report has revealed. A survey of the city’s holy buildings has revealed that 28 per cent are at risk of falling into serious disrepair – compared with an average of nine per cent in other cities. English Heritage said dwindling congregations were the main reason that church leaders had struggled to raise funds to meet spiralling repair bills. The conservation body has issued guidelines to worshippers to help teach them how to preserve the buildings for generations to come. “Churches are all that some communities have left now that post offices and pubs have closed,” said Tim Johnston, English Heritage’s director for the West Midlands. “There’s help out there but there’s also a lot that congregations can be doing to help preserve churches. We have found some buildings with serious damage to stonework just because gutters weren’t cleaned so we will be advocating the old adage about a stitch in time,’’ he said. “It’s difficult to put a finger on why Birmingham has so many churches in the risk bracket. Dwindling attendance is one factor but it seems possible that other strands of Christianity have become more prevalent than those worshipped in the more traditional church buildings.” Those in Birmingham which have been identified as “at risk” include St Edburgha’s in Yardley – the city’s second oldest church, dating back more than 800 years. Church leaders have had to stop ringing bells for fear the Grade I-listed spire could collapse and hope to start remedial work next year. Parishioners at Assemblies of the First Born on Lozells Road in Lozells also hope to move back in next year after eight years in temporary accommodation. Mortuary Chapel at Handsworth Cemetery is still being used for services but is deemed at risk while its state is assessed. St Barnabas Church in Erdington High Street is also on the list after being gutted by fire in 2007. A planning application has been approved to create a modern structure alongside the remains of the 19th century church. Singers Hill Synagogue on Blucher Street in Birmingham city centre has been given an award by English Heritage for conservation after worshippers raised thousands of pounds. The neo-classical hall, dating from 1856, has been developed as a centre for all faiths. Others singled out for praise by English Heritage chiefs include the Church of St Leonard, at Yardpole, in Herefordshire, which is home to the village’s post office and a cafe. Tapping in to the Security expert Richard J Aldrich tells Richard McComb about the threats to privacy posed by Britain’s electronic snoops. R esearching the history of GCHQ, Britain’s largest and arguably most secretive intelligence organisation, can be an unsettling experience. Just ask security expert Richard J Aldrich, who has spent most of the past decade looking into the super-snoop agency, based at Cheltenham in a circular building known as The Doughnut. Aldrich has just published GCHQ, an uncensored history of the Government Communications Headquarters, a clandestine body both feared and revered for its code-breaking exploits and covert, often highly controversial, surveillance techniques. GCHQ is the direct descendant of Bletchley Park, whose pipe-smoking cypher boffins were celebrated for cracking Nazi Germany’s wartime communications. However, the same nostalgic glow has never bathed the activities of our modern-day Station X, due in part to its growing reputation for what Aldrich calls “retail surveillance.” As his book makes clear, we are all, in a sense, being watched; and Aldrich, professor of international security at the University of Warwick, is not naive enough to think that he may have slipped under the radar. After all, snooping on the snoops – that’s just not British, is it? In his new book Richard J Aldrich, left, looks at the changing role of GCHQ, based near Cheltenham, right “It is a great relief to have finished the book so I can leave alone the lead box I have been carrying my phone around in for the last eight years,” says Aldrich. “I typed the book on a special laptop that was disabled so it didn’t connect to the internet. It’s not that I’m paranoid or anything.” That’s the thing about secrecy: it does breed paranoia. Talking to Aldrich by phone, I am aware that the line is particularly poor, muffled. They’re not listening are they? “In the United States, we know they had an intelligence programme called First Fruits which looked at journalists and historians who were studying the intelligence services. Once you see the Americans doing it, it’s only prudent to be cautious,” says Aldrich. He does offer mild reassurance about the integrity of my phone line. “One of the things that professionals tell you is that actually listening in to phones is very time-consuming. Even if you have got computers checking for key words, you have then got to listen to the transcripts,” says Aldrich. “It is much more efficient to go into people’s computers. The most important thing is to make sure you are working on a computer that doesn’t connect to the internet and then you are hygienic.” Hence the “dumb” laptop Aldrich used when writing his book. He couldn’t see them; they couldn’t see him. GCHQ is a fascinating, accessible read, detailing the development of the organisation through the Cold War, its daring intelligence-gathering operations under the Soviet fleet, the Real IRA’s bombing of Omagh and the War on Terror, which has put a monumental strain on the investigative resources of all law enforcement agencies, covert or otherwise. The wars in Iraq and now Afghanistan, and crucially, the involvement of British citizens in al-Qaida inspired terror plots on home soil, have blurred the boundaries between the remit of GCHQ, MI5 (the domestic intelligence service), MI6 (overseas intelligence) and the police. Then there has been the inexorable rise of the “wired world” with text mes- sages, email, web browsing and financial transactions casting an electronic web of our public and private movements and sparking a fundamental change in the nature of intelligence since the end of the Cold War. Aldrich says: “In the Cold War, you think of people smuggling bits of paper out of Berlin or Moscow under coat collars. Now we are dredging intelligence from much more mundane places – emails, which aren’t encoded, mobile phone conversations, which aren’t encoded, people’s Tesco loyalty cards, transport cards. The agencies are overlaying all this stuff – your credit card details, internet access details, details they have got from your car number plate off cameras – and when they overlay all that they can build up a minute picture of your life. But none of this stuff is terribly secret. It is ordinary stuff. “Our ideas of privacy are changing. Britain sent 30 billion texts last year, which are a minute description of our everyday life. Almost every five minutes we send out a little electronic signal. People put themselves on My Space and Bebo. There is a change in attitude to privacy. Privacy is dissolving to some