Journal of Applied Psychology

advertisement

Journal of Applied Psychology

1998, Vol. 83, No. 4, 654-665

Copyright 1998 by the American Psychological Association, Inc.

0021-9010/98/$3.00

Conscientiousness, Goal Orientation, and Motivation to Learn During

the Learning Process" A Longitudinal Study

Jason A. Colquitt and Marcia J. Simmering

Michigan State University

Conscientiousness and goal orientation were examined as (a) predictors of motivation

to learn and (b) moderators of reactions to performance levels during the learning process,

using an Expectancy × Valence framework. Learners (N = 103) participated in a 6week course in which an objective performance goal was assigned. Results indicated that

conscientiousness and learning orientation were positively related to motivation to learn

both initially and after performance feedback was given, whereas performance orientation

was negatively related to motivation to learn at those 2 time periods. In addition, learning

and performance orientation moderated the relationships between performance levels

during the learning process and subsequent expectancy and valence.

levels throughout the learning process, particularly in the

wake of early difficulty (Fedor, 1991; Phillips & Gully,

1997). This issue is critical because many learners struggle during the early phases of the training program and

often fall short of the objective performance goals that

are typically used (Farr, Hofmann, & Ringenbach, 1993).

Our study addressed both of these gaps by integrating

two personality variables, conscientiousness and goal orientation, with motivation to learn to assess their role in

learning. We examined these issues in the context of a 6week academic course, which provided an opportunity to

study the learning process using a more comprehensive,

longitudinal approach than many past investigations (e.g.,

Baldwin, Magjuka, & Loher, 1991; Martocchio & Webster, 1992; Phillips & Gully, 1997; Quinones, 1995). We

gave a difficult but achievable performance goal to each

learner as part of the course, matching the type of goal

normally assigned to employees in training programs and

organizational settings (Farr et al., 1993; Locke & Latham, 1990). We then examined personality relationships

at two time periods during the learning process: the beginning of the course and directly after learners were given

feedback relating their current performance levels with

their assigned goal (approximately halfway through the

course). Gagne and Medsker (1996) noted that these two

time periods are critical junctures in the learning process.

We cast conscientiousness and goal orientation as distal

variables that influenced learning through the more proximal mechanism of motivation to learn. Kanfer (1991)

advocated using this distal-proximal framework for examining personality effects because it places those effects

in a more theoretical context (see also Judge & Martocchio, 1995). We predicted that feedback regarding one's

performance levels vis-?a-vis the assigned goal would alter

subsequent motivation levels. In addition, we examined

The increasing complexity of the tasks to be performed

in the future workplace is likely to place an even greater

emphasis on training programs, as evidenced by the fact

that no less than six chapters in Howard's (1995) The

Changing Nature of Work noted the need for improved

training approaches. The increased emphasis on training

will necessitate a commitment on the part of selection

programs to provide motivated trainees. Such a commitment could create internal fit and synergy among human

resources practices, potentially improving firm performance (Becker & Gerhart, 1996; Delery & Doty, 1996).

One stream of literature that can inform practitioners in

this area is the research on motivation to learn, defined

here as a desire on the part of trainees to learn the content

of the training program (Noe, 1986).

Research has consistently shown a positive relationship

between motivation to learn and learning across a variety

of settings, but several important gaps remain. For example, research linking dispositional personality variables to

motivation to learn has been limited and often atheoretical.

In addition, researchers have not adequately explored

what types of learners continue to show high motivation

Jason A. Colquitt and Marcia J. Simmering, Eli Broad Graduate School of Management, Michigan State University.

We wish to thank John R. Hollenbeck, Raymond A. Noe,

Linn Van Dyne, and J. Kevin Ford for their helpful comments

and suggestions on an earlier draft of this article. An earlier

version of this article was presented at the 1997 meeting of the

Academy of Management, Boston, Massachusetts.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed

to Jason A. Colquitt, Eli Broad Graduate School of Management,

N475 North Business Complex, Michigan State University, East

Lansing, Michigan 48824. Electronic mail may be sent to

colquitt @pilot.msu.edu.

654

RESEARCH REPORTS

655

PERSONALITYVARIABLES

Conscientiousness

LearningOrientation

PerformanceOrientation

I

ExV

INITIAL

MOTIVATION

TO LEARN

-('-~ Pre-Feedback

w

Learning

ExV

ExV

MOTIVATION

TO LEARN

~

PoLset-Fsem

edn

ibgack

PERFORMANCE

FEEDBACK

DELIVERED

I

3 WEEKS

tI

3 WEEKS

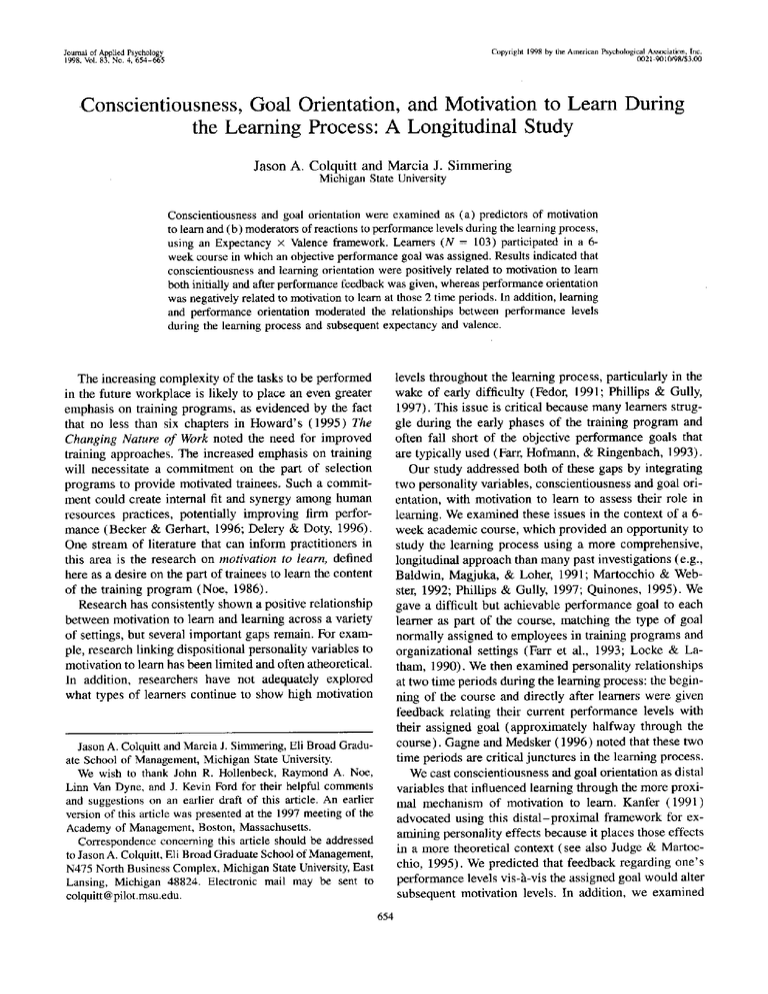

Figure 1. Conceptual model illustrating the relationships among personality variables, motivation to learn, and learning. E x V = Expectancy x Valence variables.

the degree to which learners' conscientiousness and goal

orientation levels moderated these effects, which are summarized in our conceptual model presented in Figure 1.

The Relationship B e t w e e n Conscientiousness, Goal

Orientation, and Motivation to L e a r n

Noe (1986) presented a conceptual model detailing

antecedents and outcomes associated with trainee motivation to learn. The primary antecedents in Noe's model

were job attitudes, reactions to feedback, contextual factors, and individual perceptions of self-efficacy or expectancy (i.e., effort-performance contingencies). 1 In the

decade since then, other researchers have argued that motivation to learn should be examined from both an expectancy and a valence perspective, consistent with Vroom's

(1964) expectancy theory (Baldwin & Karl, 1987; Mathieu, Tannenbaum, & Salas, 1992). This perspective asserted that trainees can desire to learn the training content

(i.e., have high levels of motivation to learn) for two

reasons: (a) They see a relationship between their effort

and actual learning progress (i.e., expectancy), and (b)

the outcomes that can be attained from such progress are

valued (i.e., valence).

Unfortunately, motivation to learn research has largely

ignored this approach, particularly in terms of valence

(e.g., Noe & Schmitt, 1986). Furthermore, even when

Expectancy x Valence approaches have been used, only

correlations with an overall summed index have been reported (Baldwin & Karl, 1987; Mathieu et al., 1992). As

a result, studies that yielded correlations between motivation to learn and attitudinal predictors (i.e., job involvement or organizational commitment) or situational predictors (e.g., the provision of choice, the framing of the

training assignment, or the presence of situational constraints) were less able to empirically show why the corre-

lation was there (Baldwin et al., 1991; Hicks & Klimoski,

1987; Martocchio & Webster, 1992; Mathieu et al., 1992;

Noe & Schmitt, 1986; Quinones, 1995; Ryman &

Biersner, 1975; Tannenbaum, Mathieu, Salas, & CannonBowers, 1991). An explicit treatment of relevant mediators, lacking in the extant literature, can help answer the

" w h y " questions that are a central component of good

theory (Whetten, 1989).

Personality variables have also been overlooked in this

research, except for locus of control, which has failed to

yield significant correlations, particularly when ability is

controlled for (Lied & Pritchard, 1976; Noe & Schmitt,

1986). Conspicuous by their absence are conscientiousness, which "may be the most important trait-motivation

variable in the work domain" (Barrick, Mount, & Strauss,

1993, p. 721 ), and goal orientation, a variable that holds

untapped promise for training applications (Button, Mathieu, & Zajac, 1996; Farr et al., 1993). An Expectancy

X Valence approach would be helpful in linking these

personality variables to motivation to learn, as evidenced

by similar efforts in the goal commitment literature (Gellatly, 1996; Hollenbeck & Klein, 1987; Hollenbeck, Williams, & Klein, 1989). Goal commitment researchers have

1Most researchers distinguish between self-efficacy (e.g.,

Bandura & Cervone, 1986) and expectancy (Vroom, 1964).

Gist and Mitchell (1992) noted that expectancy is a probabilistic

judgment regarding effort-performance contingencies that is

driven by self-efficacy, a person' s estimate of his or her "capacity to orchestrate performance on a specific task" (p. 183).

However, it is difficult to separate the two in terms of relationships to motivation to learn, possibly explaining why they were

integrated in Noe's model (e.g., Noe & Schmitt, 1986). Similarly, our study discusses both expectancy and self-efficacy as

examples of a larger expectancy component of motivational

theories (e.g., Kanfer, 1991).

656

RESEARCH REPORTS

used Expectancy × Valence approaches for personality

effects, thereby placing those effects in a more theoretical

context and responding to past criticisms of personality

research (Davis-Blake & Pfeffer, 1989; Judge & Martocchio, 1995; Kanfer, 1991). Thus, in our study, we examine

how conscientiousness and goal orientation relate to motivation to learn through the mechanisms of expectancy

and valence, as shown in Figure 1.2

search, Gellatly (1996) failed to demonstrate such a relationship. Thus, although existing research is equivocal,

we propose the following:

Hypothesis 1. Conscientiousness will be positively related

to motivation to learn, both initially and after performance

feedback is given, an effect that will be mediated by expectancy and valence.

Goal Orientation

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness, a trait reflecting qualities such as

being reliable, hardworking, self-disciplined, and persevering (McCrae & Costa, 1987), has been linked to a

variety of positive work outcomes (Barrick & Mount,

1991). Meta-analytic evidence found conscientiousness to

be a predictor of job performance across many occupational groups, and other research has linked it to goal

commitment and self-set goal setting (Barrick & Mount,

1991; Barrick et al., 1993; Gellatly, 1996). It is surprising

that no published research has used conscientiousness as a

predictor of motivation to learn. However, recent research

suggests a link between conscientiousness and expectancy. Martocchio and Judge (1997) demonstrated a significant relationship between conscientiousness and selfefficacy in a computer software training setting. In a

similar manner, Gellatly linked conscientiousness and expectancy using an arithmetic task.

These results can be explained theoretically by examining the antecedents of self-efficacy reviewed by Gist and

Mitchell (1992). For example, the authors suggested that

self-efficacy is driven in part by one's assessment of personal resources and constraints. In reflecting on their personal resources, conscientious individuals are likely to

perceive that they are diligent and hardworking

(McCrae & Costa, 1987) and should consider that a favorable resource. Another antecedent of self-efficacy is an

individual's analysis of task requirements. Conscientious

individuals are more likely to accurately assess task requirements because of their tendency to be organized and

systematic (McCrae & Costa, 1987) and should have

more confidence in their ability to meet those requirements given their traditionally high performance levels

(Barrick & Mount, 1991).

There are also reasons to expect a positive relationship

between conscientiousness and valence given that conscientiousness subsumes the more specific dimension of need

for achievement. Hollenbeck and Klein (1987) predicted a

link between need for achievement and goal commitment

because individuals with high levels of need for achievement are more likely to value high performance. Similarly,

conscientious individuals are more likely to set challenging goals for themselves and stay committed to those goals

(Barrick et al., 1993). However, although a conscientiousness-valence linkage would be consistent with this re-

Goal orientation is a relativelystable dispositional variable that assumes two forms: (a) a learning orientation

in which increasing competence by developing new skills

is the focus and (b) a performance orientation in which

demonstrating competence by meeting normative-based

standards is deemed critical. The construct was originally

derived from Dweck' s work with children in the education

domain (e.g., Dweck, 1986, 1989). Her research detailed

adaptive and maladaptive behavioral patterns that arose

on the basis of children's beliefs about ability (Dweck,

Hong, & Chiu, 1993). Entity theorists believed that ability

levels were fixed, whereas incremental theorists believed

that ability levels were malleable and could be increased.

These implicit theories affect the kinds of goals individuals choose to pursue, with entity theorists holding strong

performance goals and weak learning goals and incremental theorists showing the opposite tendency.

Much of the goal orientation research in the education

literature has used child samples (e.g., Elliott & Dweck,

1988; Seifert, 1995; Stipek & Gralinski, 1996). The extent

to which the findings of these studies generalize to adults

is still at issue, but, in general, adult samples have shown

convergent results (e.g., Archer, 1994; Bouffard, Boisvert,

Vezeau, & Larouche, 1995; Duda & Nicholls, 1992; Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1994; Greene & Miller, 1996; Harackiewicz & Elliot, 1993; Schraw, Horn, ThorndikeChrist, & Bruning, 1995). Only recently has goal orientation become a focus of organizational researchers, but

most results have supported previous research (e.g., Button et al., 1996; Fisher & Ford, in press; Hofmann, 1993;

Phillips & Gully, 1997).

Button et al. noted that goal orientation holds great

2 Vroom's (1964) conceptualization of valence differentiated

the valence of the first-order outcome, performance, and secondorder outcomes tied to performance (e.g., pay or promotions).

In an academic setting, the distinction between first- and secondorder outcomes is less clear, given that grades are outcomes

received because of performance and are direct measures of

performance itself. Thus, we referenced valence toward getting

a good grade, doing well in the course, and achieving success

in the class. Vroom also posited that valence and expectancy

are independent, a stance that contrasted with Atkinson and

Birch's (1964) theory of achievement motivation that suggested

that more difficult tasks have higher valences.

RESEARCH REPORTS

promise for organizational applications and provided several recommendations for future research. First, they provided factor analytic evidence suggesting that goal orientation is best conceptualized as two independent dimensions (learning and performance orientation) rather than

a unidimensional continuum. That is, individuals can be

simultaneously high or low on both learning and performance orientations, contrary to the conceptualization of

Dweck and her colleagues (e.g., Dweck, 1986, 1989).

The extent to which past findings in this area can be

generalized to the two-dimensional case is as yet unknown, although early research is consistent with

Dweck's predictions (Button et al., 1996; Phillips &

Gully, 1997). Finally, Button et al. further argued that

individuals have dispositional goal orientations that predispose them to react to situations in specific ways but

that situational cues can impact those predispositions.

Thus, the construct has both trait and state qualities, suggesting that test-retest reliabilities may be lower than

those of other trait measures such as conscientiousness

(Button et al., 1996; DeShon & Fisher, 1996).

Because of the implicit theories from which they are

derived, there are reasons to expect relationships between

both goal orientations and expectancy. The higher one's

performance orientation, the more one should react to

difficult tasks with doubts about ability levels (e.g., E1liott & Dweck, 1988). This relationship would explain

the finding that highly performance-oriented individuals

often avoid difficult tasks in favor of more achievable

ones (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). In contrast, the stronger

one's learning orientation, the more one should continue

to believe that ability and skill can be increased to achieve

success (e.g., Dweck, 1986, 1989). This connection suggests a positive relationship between learning orientation

and expectancy and a negative relationship between performance orientation and expectancy. Indeed, Phillips and

Gully (1997) recently demonstrated both of these predicted relationships in the context of an undergraduate

course.

There are also reasons to expect relationships between

both goal orientations and valence. Highly learning-oriented individuals are more likely to seek challenges and

view high performance as indicative of increased mastery

(Dweck & Leggett, 1988). One would therefore expect

that the more learning oriented a person is, the more he

or she would place value on high performance levels.

In contrast, Elliott and Dweck (1988) noted that, when

performance orientations are highlighted, individuals

avoid difficult tasks in favor of moderate ones (when

perceived ability is high) or easy ones (when perceived

ability is low). This finding suggests that, because the

learners in our sample were given difficult goals, performance orientation should be negatively related to valence.

Performance-oriented individuals also respond to difficult

tasks with negative affect (Dweck & Leggett, 1988; El-

657

liott & Dweck, 1988), which would also suggest a negative relationship with valence given that valence is based

on anticipated satisfaction. Therefore,

Hypothesis 2. Learning orientation will be positively related to motivation to learn, both initially and after performance feedback is given, an effect that will be mediated

by expectancy and valence.

Hypothesis 3. Performance orientation will be negatively

related to motivation to learn, both initially and after performance feedback is given, an effect that will be mediated

by expectancy and valence.

Trait Variables as Moderators of Reactions to

P e r f o r m a n c e Levels

Not all learners succeed in every facet of the learning

process--many experience some difficulty in learning the

material (Farr et al., 1993). Whether learners internally

perceive this difficulty or receive feedback regarding it,

reactions to performance levels are likely to have important motivational consequences (Ilgen, Fisher, & Taylor, 1979; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996; Phillips, Hollenbeck, &

Ilgen, 1996; Podsakoff & Farh, 1989; Taylor, Fisher, &

Ilgen, 1984). It is important to understand these consequences to maximize the effectiveness of goal-directed

learning settings. In general, researchers have shown that

low performance levels decrease expectancy and self-efficacy levels (e.g., Bandura & Cervone, 1986; Gist &

Mitchell, 1992). Relationships with valence may also be

negative, but they depend on complex cognitive and selfreactive influences such as self-satisfaction, attribution,

and referent comparison (Bandura, 1991).

In our study, we gave learners feedback halfway

through the course that related their current performance

to their assigned goal. Gagne and Medsker (1996) emphasized the importance of giving feedback during the learning process, identifying it as an instructional event that

facilitates learning. We were interested in learners' motivation in the wake of this feedback, in particular how

those effects differed according to learners' levels of conscientiousness and goal orientation. Fedor (1991) noted

that empirical research addressing the role played by personality in responding to performance feedback is needed.

Conscientiousness

Martocchio and Judge (1997) noted that conscientious

individuals have a tendency to engage in self-deception,

a notion also supported by Barrick and Mount (1996).

That is, conscientious individuals are more likely to believe that they are doing better than they truly are. This

self-deception should prevent large decreases in expectancy perceptions because such individuals may refuse to

accept the fact that poor performance levels are indicative

of true ability. Indeed, self-deceivers often reach high

658

RESEARCH REPORTS

achievement levels for this reason (Martocchio & Judge,

1997). Also, conscientious individuals, who are by definition persevering and disciplined (McCrae & Costa, 1987),

should refuse to give up in the face of difficulty. Indeed,

they should continue to hold high perceptions of valence

given their tendency to commit to assigned goals (Barrick

et al., 1993). Thus, we predict the pattern shown in Figure

2 and posit the following:

Hypothesis 4. The relationship between performance levels

at the time feedback is given and subsequent (a) expectancy

and (b) valence will be moderated by conscientiousness,

such that lower performance will be less associated with

lower expectancy or valence for highly conscientious

learners.

Goal Orientation

Goal orientation is often discussed in the context of

responses to feedback regarding performance (e.g.,

Dweck, 1986, 1989; Farr et al., 1993). Research has suggested that learning-oriented individuals should be less

likely to respond to poor progress during learning with

lowered expectancy. Button et al. (1996) demonstrated

that the more learning oriented individuals are, the more

they subscribe to the incremental theorists' position that

ability levels can be increased to correct poor progress.

Such beliefs should buffer these individuals against large

decreases in expectancy (Bobko & Colella, 1994). Moreover, individuals with strong learning orientations are

more likely to engage in problem solving and altering of

strategies when they encounter low performance levels

(Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Elliott & Dweck, 1988). In

contrast, the more performance oriented people are, the

more they believe the entity theorists' position that ability

is fixed (Button et al., 1996). Thus, these individuals

should meet difficulty with marked decreases in expec-

tancy as they shift their focus to ability inadequacies and

off-task thoughts (Bobko & Colella, 1994).

In terms of valence, research has shown that learningoriented individuals react to challenges with positive affect, pride, and intrinsic motivation (Dweck & Leggett,

1988). The more challenging a task becomes, the more it

is perceived as an opportunity to build competence. This

relationship suggests that highly learning-oriented individuals should be buffered against the tendency to associate poor performance with lower valence. Indeed, such

individuals may find themselves immersed in the task because of increased cognitive engagement (Duda & Nicholls, 1992; Greene & Miller, 1996). Performance-oriented individuals, on the other hand, traditionally do not

react to poor progress in a constructive manner. Indeed,

Fisher and Ford (in press) showed a link between performance orientation and off-task attention, and Dweck and

Leggett (1988) related performance orientation to anxiety

and negative affect. Such results suggest that these learners lack self-leadership skills (Manz, 1986) because they

focus on unpleasant aspects of the task (e.g., pressure or

uncertainty) rather than pleasant ones (e.g., challenge or

learning). Thus, the more difficulty one experiences, the

more the desire to perform well should decline. We therefore predict the pattern shown in Figure 2 and posit the

following:

Hypothesis 5. The relationship between performance at the

time feedback is given and subsequent (a) expectancy and

(b) valence will be moderated by learning orientation, such

that lower performance will be less associated with lower

expectancy or valence for highly learning-oriented learners.

Hypothesis 6. The relationship between performance at the

time feedback is given and subsequent (a) expectancy and

(b) valence will be moderated by performance orientation,

such that lower performance will be less associated with

lower expectancy or valence for less performance-oriented

learners.

The Relationship B e t w e e n Motivation

to L e a r n and Learning

-7

-6

-O

High Conscientiousness

High Learning Orientation

Low Performance Orientation

-4

-3

Low Conscientiousness

Low Learning Orientation

-2

13-

High Performance Orientation

-1

I

I

HIGH

LOW

Pre-Feedback Learning Levels

Figure 2. Predicted patterns of Personality × Learning interactions for subsequent expectancy and valence.

Linking trait variables to motivation to learn is only

valuable to the degree that motivation levels are connected

to actual learning differences. Fortunately, the relationship

between motivation to learn and learning has been robust,

predicting both cognitive and skill-based outcomes (e.g.,

Baldwin et al., 1991; Martocchio & Webster, 1992; Mathieu et al., 1992; Noe & Schmitt, 1986; Quinones, 1995;

Tannenbaum et al., 1991). On the basis of this research,

Hypothesis 7. Initial motivation to learn will be positively

related to prefeedback learning; postfeedback motivation

to learn will be positively related to postfeedback learning.

Method

Sample

The participants were 103 undergraduates enrolled in two

sections of a management course. The 6-week course was the

RESEARCH REPORTS

learning program, with performance at the midpoint of the

course (i.e., when performance feedback was given) and performance during the remainder of the course serving as the learning

measures. This paradigm has been used successfully by researchers in the areas of motivation to learn and goal setting

(Hollenbeck, Williams, & Klein, 1989; Mathieu et al., 1992;

Phillips & Gully, 1997). Hollenbeck et al. (1989) examined

goal commitment in an undergraduate management course, Phillips and Gully examined self-set goal setting in a similar setting,

and Mathieu et al. examined motivation to learn in an undergraduate bowling course. Participation was voluntary, and we

awarded extra credit points (6% of the total points) for involvement. All students participated.

Procedure

The authors served as instructors for the classes included in

the sample. Each author served as experimenter for the other

author's class; thus, no author collected data, had access to data,

or even discussed the study with his or her own students. We

asked students to participate in a term-long study involving

personality variables, and we informed them that they would

be asked to provide some academic information and to complete

several surveys. We gave the students feedback on the correlates

of various personality variables and told them how such information could be used in the workplace during the final week

of the course.

Given that reactions to learning levels were to occur as a

result of performance feedback, we had to create an objective

achievement standard, which we did by assigning each student a

goal for class performance. We collected the current cumulative

grade point average (GPA) for each participant and used it to

create a grade goal on the basis of the method used by Hollenbeck, Williams, & Klein (1989). Specifically, we added .25

points to each participant's GPA, and the resulting GPA was

then expressed as a percentage of total points on the basis of

the course's grading scale. For example, a student with a cumulative GPA of 3.25 was given a GPA goal of 3.5, which was

expressed as a grade goal of 86%. 3Thus, these goals represented

a difficult but achievable goal for student learning (Hollenbeck

et al., 1989). We distributed grade goals to the students during

the second class period in sealed envelopes marked with identification numbers. Each participant received the following explanation with the grade goal:

659

After receiving the grade goal, each student completed the

first of two in-class surveys measuring expectancy, valence, and

motivation to learn. We measured goal orientation and goal

commitment (used as a control variable) concomitantly, and we

also assessed goal orientation at the conclusion of the term.

Note that we examined goal orientation as a dispositional trait,

one that, like conscientiousness, could be used in selection batteries. However, goal orientation has been shown to have situational variability (Button et al., 1996; Dweck, 1975). Assessing

goal orientation three separate times allowed us to account for

this variance source. Specifically, we measured dispositional

goal orientation by averaging the initial, midpoint, and conclusion scores. This procedure provided us with one disposition

score because it collapsed across the contaminating influence

of situational goal orientation variance, which was outside the

scope of our study. The average correlation among the three

learning orientation scores was .62; the average correlation

among the three performance orientation scores was .60. This

level is consistent with other uses of Button et al.'s measure

(DeShon & Fisher, 1996).

The first course examination was given 2 weeks (four class

periods) after students received their grade goals. We recorded

performance on this examination in percentage terms, and participants received performance feedback during the class period

immediately following the exam. This feedback read as follows:

"Your grade goal at the beginning of the semester was a

%.

Your current grade in the course is a

%. That means you

are currently

% (above/below) your grade goal." During

the subsequent class meeting, students completed the second inclass survey, which again assessed expectancy, valence, motivation to learn, goal orientation, and goal commitment.

We gave the final examination for the course 3 weeks (five

class periods) after the administration of the grade goal feedback, and we used it to assess learning at the conclusion of the

learning process. We gave the final goal orientation measure at

the beginning of this class period. We also gave participants a

separate out-of-class survey that assessed conscientiousness and

asked them to complete the scale on their own time. We collected

all scales at least 2 weeks before the end of the course.

Measures

Your goal for a grade in this course is: _ _ %

Motivation to learn. We used three items adapted from Noe

and Schmitt (:1986) to measure motivation to learn. One example included, "I will exert considerable effort in learning this

material" ( 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; as =

.75 initially and .83 postfeedback).

Expectancy. We used both expectancy-based and self-efficacy-based measures to tap this construct. The expectancy measure consisted of two items from Lawler and Suttle (1973). We

asked participants to indicate how true it was that the first phrase

of a pair leads to the second phrase of a pair, for them personally,

in the context of the course. Pairs included, (a) "trying hard --*

Please note that this goal will in no way prevent you from

attaining a higher grade in this course. It is not an indication

of the grade you are capable of receiving, only a guideline

that you can use to track your performance. Your instructor

has no knowledge of your goal, and achievement of the

goal (or lack of achievement) will have no bearing on your

grade whatsoever. Good luck this semester!

3 Eight students had GPAs of 3.76 of higher, which created a

ceiling for their grade goals because students could not earn

more than 100% in the course. Thus, all analyses were run with

and without this group. In no cases did the results differ in

either significance level or effect size.

Goal setting theory suggests that people perform well when

they are assigned difficult and specific goals. Research has

found that a difficult goal for a student's performance in a

course is approximately .25 points higher than his or her

cumulative grade point average. Based on your grade point

average, we have given you a difficult and specific goal for

this course.

660

RESEARCH REPORTS

learning the material" and (b) "putting forth effort --* gaining

an understanding of the material." We assessed self-efficacy

with three items from Mclntire and Levine (1984). One example included, " I do well in activities where I have to remember

lots of information ''4 (1 = never to 7 = always; a s = .66

initially and .70 postfeedback).

Valence. We used three items adapted from Lawler and Suttle (1973) to assess valence. We asked participants to indicate

"how desirable" (in the context of the course) they considered

(a) "getting a good grade," (b) "doing well in the course,"

and (c) "achieving success in the class" to be ( 1 = very undesirable to 7 = very desirable; as = .63 initially and .64

postfeedback).

Conscientiousness. We used the 12-item scale from the

NEO Five-Factor Inventory, a shorter version of the NEO Personality Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1992), to measure conscientiousness (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; a =

.79 ). Costa and McCrae (1992) reported test-retest reliabilities

of .83 for this scale, suggesting that the variable has a definite

trait quality.

Goal orientation. We used Button et al.'s (1996) eight-item

dispositional goal orientation measures. Learning orientation

items included, "I prefer to work on tasks that force me to learn

new things" and "The opportunity to do challenging work is

important to me." Performance orientation items included,

"Once I find the right way to do something, I stick to it" and

"The things I enjoy the most are the things I do best." (1 =

strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; as = .83 for leaming

orientation and .80 for performance orientation). Button et al.

provided reliability and construct validity evidence for these

scales. We computed coefficient alphas by treating each of the

three learning orientation and performance orientation scores

(i.e., initial, midpoint, and conclusion) as one item in a threeitem scale.

Prefeedback learning. We assessed prefeedback learning

through the first course examination. This examination consisted

of 60 items (100 points) that assessed declarative knowledge.

Postfeedback learning. We assessed postfeedback learning

through the final course examination, which again consisted of

60 items (100 points) that assessed declarative knowledge.

Control variables. Three control variables were used. GPA

served as a control to ensure that performance or motivation

variance due to ability could be captured. This control was

especially critical because the .25-point increase in grade

seemed more difficult to learners with low GPAs. We also coded

class membership because it was likely a contaminant that explained performance and motivation variance due to nonrandom

assignment of students to classes. A score of 0 was given to

students in Jason A. Colquitt's class; a score of 1 was given to

students in Marcia J. Simmering's class. Finally, we controlled

for goal commitment to statistically ensure that all learners were

equally committed to their assigned goals, given that such commitment should relate to performance and motivation, particularly after feedback is delivered. Indeed, Bobko and Colella

(1994) noted that reactions to performance standards should

depend on the degree to which those standards are accepted by

the individual. Thus, we used Hollenbeck, Klein, O'Leary, and

Wright's (1989) four-item goal commitment scale ( 1 = strongly

disagree to 7 = strongly agree; a s = .69 initially and .69

postfeedback), and it should be noted that commitment levels

were generally high (M = 5.11 out of 7; SD = 1.02).

Results

D e s c r i p t i v e Statistics

The means, standard deviations, and zero-order intercorrelations o f all variables are reported in Table 1. Coefficient alphas are shown in the diagonal o f the correlation

matrix. Several correlations o f variables never included

together in a single study are notable. For example, conscientiousness was positively associated with learning orientation levels and negatively associated with performance

orientation levels. Goal c o m m i t m e n t was positively related to motivation to learn, as well as valence and expectancy. Finally, conscientiousness had a significant positive

correlation with goal c o m m i t m e n t and learning, whereas

performance orientation was negatively correlated with

learning ( p o s t f e e d b a c k ) .

Tests o f H y p o t h e s e s

Hypotheses 1 - 3 predicted that the relationships between the personality variables and motivation to learn

w o u l d be mediated by valence and expectancy. The results

are shown in Table 2. A l l three personality variables explained significant incremental variance in motivation to

learn b e y o n d the effects o f the control variables. Consistent with our predictions, the personality variables explained less variance in motivation to learn when the Expectancy X Valence variables were statistically controlled.

However, conscientiousness and learning orientation still

explained significant incremental variance, suggesting

that their relationships with motivation to learn were only

partially mediated. 5 The directions o f these relationships

were all as predicted (see Table 1): Conscientiousness

and learning orientation were positively correlated with

expectancy, valence, and motivation to learn, and performance orientation was negatively correlated with expectancy and motivation to learn. Contrary to predictions,

performance orientation was unrelated to valence.

To c o m p l e m e n t the above analyses, we e x a m i n e d the

4 We conducted a principal components factor analysis with

varimax rotation to test the unidimensionality of the larger expectancy variable. A one-factor solution fit the data, suggesting

that the expectancy and self-efficacy items could in fact be

combined.

5 The fact that the relationships between conscientiousness

and goal orientation and motivation to learn were only partially

mediated by Expectancy x Valence variables suggests that significant correlations with motivation to learn are not simply a

function of common method variance. Presumably, controlling

for other self-report variables would remove variance due to

common methods and same-source bias.

RESEARCH REPORTS

relationship between the three personality variables (entered simultaneously) and motivation to learn. Personality

variables explained an incremental 28% of the variance

in prefeedback motivation to learn (p < .001 ), with both

conscientiousness (/~ = .33, p < .001 ) and learning orientation (/~ = .38, p < .001 ) having significant independent

relationships. Personality variables explained an incremental 27% of the variance in postfeedback motivation

to learn (p < .001 ), again with both conscientiousness

(fl = .28, p < .01 ) and learning orientation (/~ = .40, p <

.001 ) having significant independent relationships. These

results have practical significance in addition to statistical

significance. To express this, we classified learners into

positive and negative trait patterns, where a positive pattern represented high learning orientation, high conscientiousness, and low performance orientation, and expressed

the correlation between this pattern and motivation to

learn using a binomial effects size display (Rosenthal &

Rosnow, 1991). Compared with learners with a negative

pattern, learners with a positive pattern were 38% more

likely to be motivated before feedback and 40% more

likely to be motivated after feedback. They were also 30%

more likely to perform well on the first exam and 28%

more likely to perform well on the second. 6

Hypotheses 4 - 6 predicted interactions among the personality variables and prefeedback learning levels for

postfeedback expectancy and valence. We assessed these

hypotheses using moderated multiple regression; results

are presented in Table 3. No interactions were demonstrated for conscientiousness. However, interactions were

demonstrated for learning orientation with postfeedback

expectancy and performance orientation with postfeedback valence, with the pattern matching that shown in

Figure 2.

Hypothesis 7 predicted that motivation to learn would

be positively related to pre- and postfeedback learning.

Initial motivation to learn explained an additional 2% of

the variance in prefeedback learning (/~ = .14, p < .05)

beyond the three control variables, which accounted for

45% of the learning variance. Postfeedback motivation to

learn added 4% of the variance explained for postfeedback

"a

t,~

II

=<

e!

o

I

rl

00

o

.-....=.~

r---

I

H

II

o

I

.,=

II

~ 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

.....

ol

g

~ . . ~ . . .

~1

661

o

I

i

g

ca,

r.~

...........

~

;>

-

~ .

I

-~.~.~

.,= ~ ~= ~.=

o=~

=~.~ ~ ~ -

II

~ ~<~

~

>

,~2~v

0

.

6 Rosenthal and Rosnow (1991) expressed practical significance by putting a criterion into dichotomous terms such as

"perform well" or "perform poorly" and "motivated" or "unmotivated" using median splits. This convention is applied here

because it is congruent with the context of many training programs in which some cutoff must be achieved to fulfill a requirement or move on to a subsequent course. Relationships with

this dichotomous criterion are then expressed in percentage

terms, where the percentages are calculated by 50% _+ r/2.

Thus, the correlation between our positive trait pattern and prefeedback learning of r = .30 translates into 65% (50 + 15) and

35% (50 - 15), or a 30% difference (65 - 35) in the likelihood

of performing well based on trait patterns.

662

RESEARCH REPORTS

Table 2

Variance Explained in Motivation to Learn by Personality Variables

Personality variable

Initial motivation to learn (DV)

Postfeedback motivation to learn (DV)

Predictor

Conscientious

Learning

oriented

Performance

oriented

Conscientious

Learning

oriented

Performance

oriented

1. Class a

2. GPA a

3. Goal commitment"

4. Personality variable

Controlling for E × V

1. Class"

2. GPAa

3. Goal commitment~

4. Expectancy

5. Valence

6. Personality variable

.00

.00

.15"**

.28***

.00

.00

.15"**

.35***

.00

.00

.15"**

.17*

.02

.00

.11 **

.10"*

.02

.00

.11"*

.20***

.02

.00

.11 **

.04*

.00

.00

.15" **

.05**

.10"**

.08**

.00

.00

.15"**

.05**

.10"**

.13***

.00

.00

.15 ***

.05**

.10"**

.02

.02

.00

.11 **

.02

.22***

.05**

.02

.00

.11 **

.02

.22***

.09***

.02

.00

.11 **

.02

.22***

.02

Note. Values represent AR2s. N = 103. All equations had an overall F-statistic significance o f p < .001. GPA = cumulative grade point average;

E × V = Expectancy × Valence; DV = dependent variable.

"Control variables.

* p < .05. * * p < .01. * * * p < .001.

learning (/3 = .13, p < .05) beyond the three control

variables, which accounted for 54% of the learning variance. Thus Hypothesis 7 was supported. The fact that the

hypothesis was supported despite the marginal significance of the motivation-to-learn correlations in Table 1

illustrates the importance of the control variables.

Table 3

Regression Results for Moderation Hypotheses

Personality variable

Predictor

Conscientious

Learning

oriented

Performance

oriented

DV = Postfeedback expectancy a

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Class h

GPA b

Goal commitmentb

Initial expectancy

Personality variable

Learning

Personality × Learning

,00

.04*

.04"

.30"**

,01

.04*

.01

.00

.04*

.04*

.30"**

.02

.03*

.04**

.00

.04*

.04"

.30***

.00

.03*

.00

DV = Postfeedback valence ~

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Class ~

GPA b

Goal commitmentb

Initial valence

Personality variable

Learning

Personality × Learning

.00

.00

.03

.53***

.01

.00

.00

.00

.00

.03

.53***

.00

.00

.00

.00

.00

.03

.53***

.00

.00

.02*

Note. Values represent ARes. N = 103. All equations had an overall

F-statistic significance of p < .001. GPA = cumulative grade point

average; DV = dependent variable.

"Hypotheses 4, 5, and 6--expectancy. b Control variables, c Hypotheses 4, 5, and 6--valence.

* p < .05. * * p < .01. * * * p < .001.

Discussion

The positive relationships of learning orientation and

conscientiousness with motivation to learn stand out as

the most important contributions of this study. Learners

who had high levels of these personality variables exhibited higher motivation levels, both initially and in the wake

of feedback during the learning process. Furthermore, we

elucidated the underlying mechanisms for these effects

using an Expectancy x Valence framework, placing these

relationships in a more established theoretical context.

Specifically, the relationships of conscientiousness and

motivation to learn were partially mediated by expectancy

and valence. In other words, individuals who were reliable, self-disciplined, and persevering were more likely

to perceive a link between effort and performance and

were more likely to value high performance levels. These

results therefore complement past research by identifying

mechanisms for positive manifestations of this personality

variable (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Barrick et al., 1993).

Learning orientation was also related to motivationto-learn levels, with highly learning-oriented individuals

exhibiting higher expectancy and valence levels. In contrast, performance orientation was negatively related to

motivation to learn by means of expectancy. Thus, this

study is among the first to demonstrate a significant link

between goal orientation and two of the most visible motivational constructs, expectancy and valence. Our work

therefore places goal orientation (and conscientiousness)

in a larger, metatheoretical framework of Expectancy ×

Valence theories, allowing their relationships to be compared and contrasted with those of other trait and motivation variables (Kanfer, 1991).

RESEARCH REPORTS

Besides predicting motivation levels, the personality

variables we examined also moderated individuals' responses to performance levels during the learning process.

Although the role of personality in reacting to performance levels and feedback has been much discussed, empirical work is lacking (Fedor, 1991). Our work begins

to fill this gap by showing that the tendency for low performance levels to be associated with lower expectancy levels was less prevalent for highly learning-oriented individuals. This finding is consistent with past goal orientation

research suggesting that learning orientations buffer learners against the negative effects of early difficulty (Button

et al., 1996; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Elliott & Dweck,

1988). Furthermore, the tendency for low performance to

be associated with lower valence was not as prevalent for

less performance-oriented individuals, an effect that has

not been demonstrated in past research. Thus, in situations

in which difficulty in mastering training content is expected, our results suggest that highly learning-oriented

individuals (and less performance-oriented individuals)

should remain motivated. We observed no interactions

for conscientiousness; rather, its effects were uniformly

positive across performance levels.

Taken together, these results have many practical implications. As noted above, learners with a trait pattern that

was highly conscientious, highly learning oriented, and

less performance oriented were 30% more likely to perform well on the first exam and 28% more likely to perform well on the second using Rosenthal and Rosnow's

(1991) convention. Because conscientiousness is used in

many selection batteries and has shown considerable stability (test-retest r = .83; Costa & McCrae, 1992), information about the conscientiousness of learners could be

a valuable component of the person analysis phase of

needs assessment (Goldstein, 1991). Goal orientation

measures could be used in a similar fashion, or the training

context could be manipulated to enhance one orientation

or the other. Dweck (1975) and Kraiger, Ford, and Salas

(1993) noted that situational cues can affect a learner's

orientation at a given point in time, giving a state component to the construct (Button et al., 1996; DeShon &

Fisher, 1996). Thus, in situations in which training materials are particularly complex and learning difficulty is expected, conscientious and learning-oriented individuals

could be selected for training, or a learning-oriented emphasis could be created by illustrating task experimentation and exploration of multiple learning strategies. In

situations in which conscientious individuals are lacking

or a learning-oriented emphasis is impossible, training

may need to be lengthened and learning rate slowed so

students can avoid early difficulty. Also, given the lower

valence levels among such individuals, external incentives

may be necessary to improve their motivation to learn.

A potential limitation of this study is that the learning

occurred in a classroom setting rather than in an actual

663

organizational training environment. However, because

we were interested in the effects of personality variables

in an achievement-oriented setting, the classroom did afford a high degree of fidelity. Specifically, Farr et al.

(1993) noted that most of the goals advanced in organizations are normative performance goals. Such goals are

also most frequently used in training programs, which

often culminate in objectively scored achievement tests.

Nonetheless, future research is needed to replicate these

findings in other types of learning environments, including

those in which explicit rewards are tied to goal achievement. Although many goals in organizational settings are

only loosely tied to objective rewards, the presence of such

rewards could increase the motivational ramifications of

outcome valence. In the current study, learners received

no specific awards for goal achievement. However, to the

extent that awards increase goal commitment (e,g., Hollenbeck & Klein, 1987), controlling for goal commitment

in all our analyses suggests that our results may be generalizable to such contexts.

In addition, researchers should replicate these findings

with other types of goals (e.g., mastery goals) and with

other forms of feedback. Fedor ( 1991 ) notes that feedback

is multidimensional, including facets such as sign, accuracy, timing, quantity, and specificity. To this we would add

that feedback can be subjective or objective, process or

outcome oriented, task or person generated, interactionally

fair or unfair (Bies & Moag, 1986), written or oral, individual or group level, or surprising or expected. Fedor notes

that individual differences affect preferences for certain

dimensions of feedback. It may be that personality variables

moderate reactions to feedback differently according to

these dimensions. For example, learning orientation may

be a more significant moderator when process feedback is

given or when feedback is task generated. Conscientiousness may be more necessary when subjective, interactionally unfair feedback is given. Performance orientation

may be more deleterious to individuals who receive negative feedback when it is surprising to them. Moreover, our

results may become less significant when feedback is general, brief, delayed, or inaccurate because the information

needed to alter behavior is not provided. These types of

feedback occur across a variety of training settings, depending on whether procedural or declarative knowledge

is emphasized (Kraiger et al., 1993), whether tasks amenable to objective feedback are used, and whether trainers

are experienced in feedback delivery. Future research on

personality effects in these domains is warranted.

References

Archer, J. (1994). Achievement goals as a measure of motivation

in university students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19, 430-446.

Atkinson, J. W., & Birch, D. (1964). An introduction to motivation. Princeton, NJ: Van Norstrand.

664

RESEARCH REPORTS

Baldwin, T.T., & Karl, K. (1987, August). The development

and empirical test of a measure for assessing motivation to

learn in management education. Paper presented at the 47th

Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, New Orleans, LA.

Baldwin, T. T., Magjuka, R. J., & Loher, B. T. ( 1991 ). The perils

of participation: Effects of learner choice on motivation and

learning. Personnel Psychology, 44, 51-66.

Bandura, A. ( 1991 ). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50,

248-287.

Bandura, A., & Cervone, D. (1986). Differential engagement

of self-reactive influences in cognitive motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 38, 92-113.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. ( 1991 ). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, 1-26.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1996). Effects of impression

management and self-deception on the predictive validity of

personality constructs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80,

500-509.

Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Strauss, J. P. (1993). Conscientiousness and performance of sales representatives: Test of

the mediation effects of goal setting. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 715-722.

Becket, B., & Gerhart, B. (1996). The impact of human resource

management on organizational performance: Progress and

prospects. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 779-801.

Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. E (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. In R.J. Lewicki, B.H. Sheppard, & M. H. Bazerman (Eds.), Research on negotiations

in organizations (Vol. 1, pp. 43-55). Greenwich, CT: JAI

Press.

Bobko, E, & Colella, A. (1994). Employee reactions to performance standards: A review and research propositions. Personnel Psychology, 47, 1-29.

Bouffard, T., Boisvert, J., Vezeau, C., & Larouche, C. (1995).

The impact of goal orientation on self-regulation and performance among college students. British Journal of Educational

Psychology, 65, 317-329.

Button, S. B., Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. M. (1996). Goal orientation in organizational research: A conceptual and empirical foundation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67, 26-48.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). The NEO PI-Rprofessional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment

Resources.

Davis-Blake, A., & Pfeffer, J. (1989). Just a mirage: The search

for dispositional effects in organizational research. Academy

of Management Review, 14, 385-400.

Delery, J.E., & Doty, D.H. (1996). Modes of theorizing in

strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic,

contingency, and configurational performance predictions.

Academy of Management Journal, 39, 802-835.

DeShon, R. P., & Fisher, S. L. ( 1996, April). Goal orientation:

Weaving the nomological net. Symposium conducted at the

12th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and

Organizational Psychology, St. Louis, MO.

Duda, J. L,, & Nicholls, J. G. (1992). Dimensions of achieve-

ment motivation in schoolwork and sport. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 290-299.

Dweck, C. S. (1975). The role of expectations and attributions

in the alleviation of learned helplessness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 674-685.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning.

American Psychologist, 41, 1040-1048.

Dweck, C, S. (1989). Motivation. In A. Lesgold & R. Glaser

(Eds.), Foundations for a psychology of education (pp. 87136). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dweck, C. S., Hong, Y., & Chiu, C. (1993). Implicit theories:

Individual differences in the likelihood and meaning of dispositional inference. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19, 644-656.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review,

95, 256-273.

Elliot, A.J., & Harackiewicz, J.M. (1994). Goal setting,

achievement orientation, and intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

66, 968-980.

Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to

motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and SoCial Psychology, 54, 5-12.

Farr, J. L., Hofmann, D. A., & Ringenbach, K. L. (1993). Goal

orientation and action control theory: Implications for industrial and organizational psychology. International Review of

Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8, 193-232.

Fedor, D. B. ( 1991 ). Recipient responses to performance feedback: A proposed model and its implications. In G.R.

Ferris & K. M. Rowland (Eds.), Research in personnel and

human resource management (Vol. 9, pp. 73-120). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Fisher, S.L., & Ford, J. K. (in press). Differential effects of

learner effort and goal orientation on two learning outcomes.

Personnel Psychology.

Gagne, R.M., & Medsker, K.L. (1996). The conditions of

learning: Training applications. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt

Brace.

Gellatly, I. R. (1996). Conscientiousness and task performance:

Test of a cognitive process model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 474-482.

Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Academy of

Management Review, 17, 183-211.

Goldstein, I.L. (1991). Training in work organizations. In

M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 507-620).

Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Greene, B. A., & Miller, R. B. (1996). Influences on achievement: Goals, perceived ability, and cognitive engagement.

Contemporary Educational Measurement, 21, 181 - 192.

Harackiewicz, J. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1993). Achievement goals

and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 65, 904-915.

Hicks, W. D., & Klimoski, R. (1987). The process of entering

training programs and its effect on training outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 30, 542-552.

Hofmann, D. A. (1993). The influence of goal orientation on

task performance: A substantively meaningful suppressor

RESEARCH REPORTS

variable. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 18271846.

Hollenbeck, J. R., & Klein, H. J. (1987). Goal commitment and

the goal-setting process: Problems, prospects, and proposals

for future research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 212220.

Hollenbeck, J. R., Klein, H. J., O'Leary, A. M., & Wright, P. M.

(1989). Investigation of the construct validity of a self-report

measure of goal commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology,

74, 1-6.

Hollenbeck, J. R., Williams, C. R., & Klein, H. J. (1989). An

empirical examination of the antecedents of commitment to

difficult goals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 18-23.

Howard, A. (1995). The changing nature of work. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ilgen, D.R., Fisher, C.D., & Taylor, M.S. (1979). Consequences of individual feedback on behavior in organizations.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 64, 349-371.

Judge, T. A., & Martocchio, J. J. ( 1995, May). Dispositions and

work outcomes. Symposium conducted at the annual meeting

of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology,

Orlando, FL.

Kanfer, R. ( 1991 ). Motivation theory and industrial and organizational psychology. In M.D. Dunnette & L.M. Hough

(Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 75-170). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback

interventions on performance: A historical review, a metaanalysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 1-31.

Kraiger, K., Ford, J. K., & Salas, E. (1993). Application of

cognitive, skill-based, and affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 311-328.

Lawler, E. E., & Suttle, J. L. (1973). Expectancy theory and

job behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 9, 482-503.

Lied, T. R., & Pritchard, R. D. (1976). Relationships between

personality variables and components of the expectancyvalue model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61, 463-467.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting

and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Manz, C. C. (1986). Self-leadership: Toward an expanded theory of self-influence processes in organizations. Academy of

Management Review, 11, 585-600.

Martocchio, J. J., & Judge, T. A. (1997). Relationship between

conscientiousness and learning in employee training: Mediating influences of self-deception and self-efficacy. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 82, 764-773.

Martocchio, J.J., & Webster, J. (1992). Effects of feedback

and cognitive playfulness on performance in microcomputer

software training. Personnel Psychology, 45, 553-578.

Mathieu, J. E., Tannenbaum, S. I., & Salas, E. (1992). Influences of individual and situational characteristics on measures

of training effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal,

35, 828-847.

665

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, E T, Jr. (1987). Validation of the fivefactor model of personality across instruments and observers.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81-90.

McIntire, S.M., & Levine, E.L. (1984). Task specific selfesteem: An empirical investigation. Journal of Vocational

Behavior, 25, 290-303.

Noe, R. A. (1986). Trainee attributes and attitudes: Neglected

influences on training effectiveness. Academy of Management

Review, 11, 736-749.

Noe, R.A., & Schmitt, N. (1986). The influence of learner

attitudes on training effectiveness: Test of a model. Personnel

Psychology, 39, 497-523.

Phillips, J. M., & Gully, S. M. (1997). Role of goal orientation,

ability, need for achievement, and locus of control in the selfefficacy and goal-setting process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 792-802.

Phillips, J. M., Hollenbeck, J. R., & Ilgen, D. R. (1996). Prevalence and prediction of positive discrepancy creation: Examining a discrepancy between two self-regulation theories.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 498-511.

Podsakoff, P.M., & Farh, J.L. (1989). Effects of feedback

sign and credibility on goal setting and task performance.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 44,

45-67.

Quinones, M. A. (1995). Pretraining context effects: Training

assignment as feedback. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80,

226-238.

Rosenthal, R. & Rosnow, R. L. ( 1991 ). Essentials ofbehavioral

research: Methods and data-analysis. New York: McGrawHill.

Ryman, D. H., & Biersner, R. J. (1975). Attitudes predictive of

diving training success. Personnel Psychology, 28, 181 - 188.

Schraw, G., Horn, C., Thorndike-Christ, T., & Bruning, R.

(1995). Academic goal orientations and student classroom

achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 20,

359-368.

Seifert, T L. (1995). Academic goals and emotions: A test of

two models. Journal of Psychology, 129, 543-552.

Stipek, S., & Gralinski, J. H. (1996). Children's beliefs about

intelligence and school performance. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 88, 397-407.

Tannenbaum, S. I., Mathieu, J. E., Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers,

J.A. (1991). Meeting trainees' expectations: The influence

of training fulfillment on the development of commitment,

self-efficacy, and motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology,

76, 759-769.

Taylor, M. S., Fisher, C. D., & Ilgen, D. R. (1984). Individuals'

reactions to performance feedback in organizations: A control

theory perspective. In K. M. Rowland & G. R. Ferris (Eds.),

Research in personnel and human resource management

(Vol. 2, pp. 81-124). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York: Wiley.

Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14, 490-495.

Received June 23, 1997

Revision received January 20, 1998

Accepted January 20, 1998 •