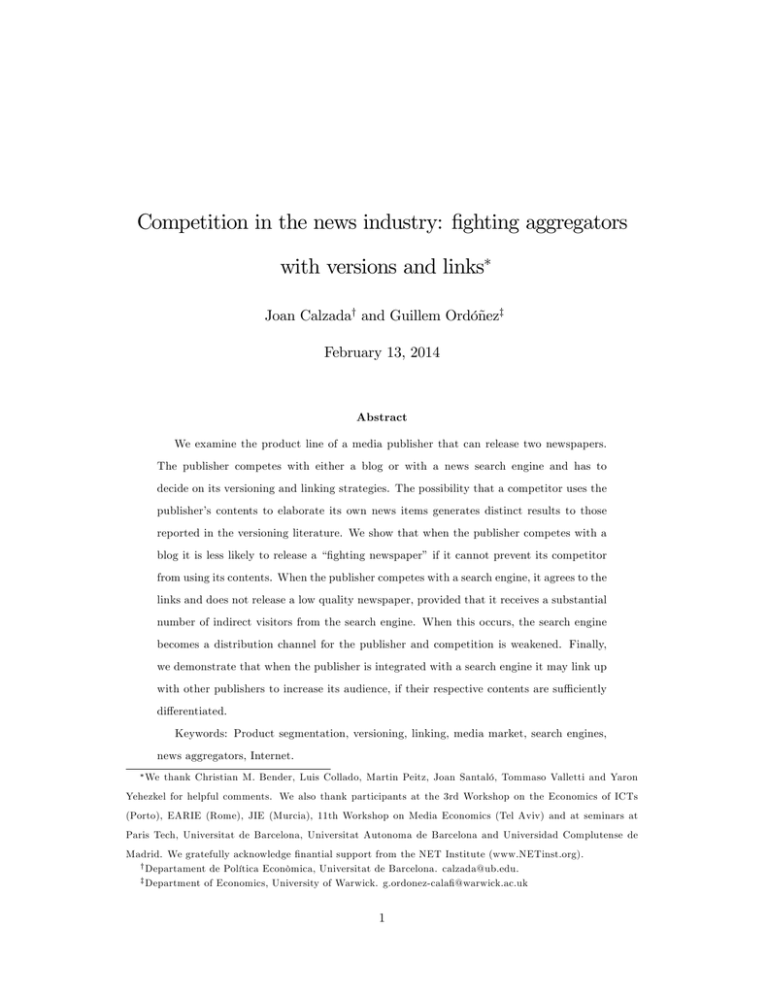

Competition in the news industry: …ghting aggregators with versions and links

advertisement