Journal of Educational and Psychological Studies JEPS

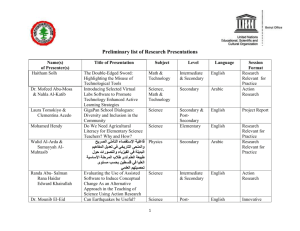

advertisement