Profit-Sharing Versus Fixed-Payment Contracts: Evidence From the Motion Pictures Industry

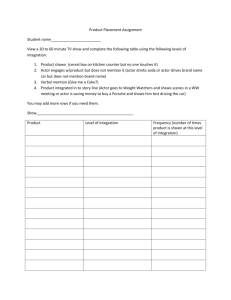

advertisement