Dollars Driven by What States Should Know When Considering

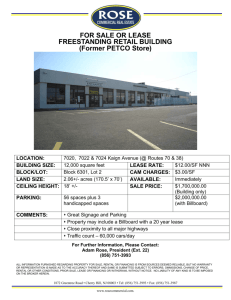

advertisement